A day later, SF Opera presented the World Premiere of John Adams’ new opera Antony and Cleopatra based on Shakespeare’s tragedy, a work specifically commissioned for the Centennial. The piece is co-commissioned and co-produced by the Metropolitan Opera and The Gran Teatre del Liceu Barcelona, and it was announced that the work will also travel to Palermo.

Antony and Cleopatra is the fifth Adams opera that has graced the War Memorial stage, following The Death of Klinghoffer in 1992, Doctor Atomic (which also received its world premiere here) in 2005, Nixon in China in 2012 and Girls of the Golden West (another world premiere) five years ago, which was reviewed here by my predecessor John Masko.

It also marked a significant shift from Adams’ regular collaborator and librettist Peter Sellars, as this time he worked closely with director Elkhanah Pulitzer and dramaturg Lucia Scheckner in adapting Shakespeare’s sprawling materials into an opera with 10 scenes (in two acts) and with only 12 characters. (With all that trimming, Adams only managed to shave off slightly more than half hour of the usual running time of the play!)

In a program note, Adams detailed his approach in transforming Shakespeare’s love story in the middle of political intrigue and clash of civilizations.

“One never knows how different the reality will be from what began in the mind’s eye, but I am fairly certain that Antony and Cleopatra, in comparison to all my earlier stage works, differs by being the most actively dramatic. There are fewer stand-alone set pieces (arias, choruses, etc.). In their place I tried to maintain a fast-moving interaction among the characters. These characters, rather than pondering in song their doubts, designs, or motivations, act on them directly. In this sense, although it is of course musically much different, the model of “sung drama” that Debussy imagined in Pelléas et Mélisande is probably the closest to my aims.”

With such a lofty ambition to create a “sung drama”, Adams mostly succeeded, particularly in the excellent first act. True to his words, he eschewed traditional aria-based structure even for both title characters, resulting the actions move in such a breakneck pace that, in my opinion, were even faster than Giuseppe Verdi’s Shakespeare-adaptation Falstaff (another mentioned inspiration).

Adams’ declamatory vocal writing set Shakespeare lines by lines in a rapid manner (most of them were unrepeated), accentuated by the powerfully percussive score highlighting Adams’ mastery in orchestration. The orchestral characterization of The Battle of Actium was particularly a highlight, and I wouldn’t be surprised if it became a staple in many symphony halls!

However, the approach did pose a challenge for the audience. First, it required the audience to have some familiarity with three things: Antony and Cleopatra story in general, the characters of the play and Shakespeare’s stylized English language full of metaphors and conceits (something that I, as a non-English native speaker, struggled with). There was no warm-up for the audience, as they were thrown straight into action and propelled into the following scenes. Luckily, SF Opera provided a cheat sheet on the program to help to identify the characters.

In my opinion, the lack of exposition also hindered the audience from having close emotional affinity to the characters of Antony and Cleopatra. That lack became a problem in second half of the opera. In fact, it felt like both title characters spent most of first act alternating between sex-crazed and scheming stages!

The lightning speed of Act 1 came to a screeching halt for the second half of the opera, where the mood turned somber, as if aware of the impending tragedy. Adams’ music for this part was evocative of night-time, where the comparison with Pelléas et Mélisande was more apt. (Although, to my ears, it reminisced more of the score of another star-crossed lovers, Tristan und Isolde.)

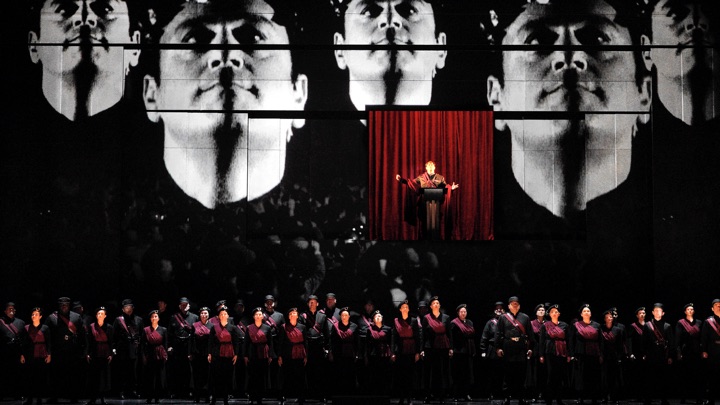

In this Act, I wish Addams exercised more constraints particularly in highly repetitive Scene 2, where Caesar was supposedly to (to quote words from the Synopsis) “give a rousing speech to the populace, proclaiming Rome’s absolute dominance over the known world’, with texts lifted from Virgil’s The Aeneid (by way of John Dryden’s English translation).

Sung by Caesar with the chorus enthusiastically hailed his ascendance in red and black militaristic garb, I suppose the scene depicted a cautionary tale of the danger of the rise of fascism, but it went on and on and on, reducing its effectiveness and turned it into more of a freak show (especially coupled with the fact that Caesar’s face was projected on stage in increasing number!)

Similarly, the extended death scene for Antony that followed right after would probably benefit from some trimming as the sight of Antony collapsing and then rallying numerous times (at one point even drew chuckles from audience) while singing all those Shakespeare lines seemed an emotional overkill. By contrast, the demise of Cleopatra (arguably the most important character in the opera) at the end was quite brisk!

In her Director’s Note, Pulitzer said that “In updating the setting, we chose to invoke the Golden Age of Hollywood, which feels particularly apt, given how cinematic depictions of these characters have become enmeshed with the genre’s own history and still influence modern perceptions.”

Much had been said about the 1930s Golden-Age Hollywood “Art Deco” style that inspired both Mimi Lien’s sets and Constance Hoffman’s costumes in an illuminating article published just a day prior the opening. Hoffman manifested that inspiration in the seven extraordinarily colorful costumes for Cleopatra, while Lien took cue from the famous “Entrance to Rome” scene from Joseph L. Mankiewicz’s 1963 film Cleopatra starring Elizabeth Taylor: “During her entrance to Rome (being pulled on a giant sphinx) she has on this stepped headdress; we used that and this black obsidian quality of the sphinx all over the set. I wanted it to be quite simple and geometric and abstract.”

Cleopatra’s costumes were truly a sight to behold; the various shades of metallics employed squarely put the spotlight on her every time she was on stage, and I had no doubt that was intentional, as Pulitzer put it: “My way into the story was through Cleopatra, for whom I have a deep affection.”

However, I couldn’t shake the feeling that Hoffman missed the mark in costuming the rest of the characters – particularly of the men – who dressed simply in various types of military uniform. I was initially delighted to see that Hoffman used a specific color scheme to denote the camps (Team Octavian in navy blue and Team Antony in white) in the Scene 2 confrontation as such device provided a great help in identifying who’s who, but Hoffman abandoned the idea and settled to various earthy tones (predominantly brown and green) plus the aforementioned red/black ensemble for Caesar’s admirers.

Even Antony himself spent the rest of opera in light brown getup, only adorned by a breastplate during the battle scenes. It was truly a missed opportunity, methinks!

Lien’s sets consisted of two primary stage units, a trapezoidal moveable stack of panels in front (no doubt indicating a cross-section of a pyramid) and a spinning larger set as a backdrop (most effectively to represent a silhouette of another pyramid).

They were pretty genius designs, as the adjustable panels moved around to display a certain section of the stage where a certain scene was happening, super effective in the fast-paced actions in Act 1. However, as stated above, the panels were in “obsidian black” color, resulting that whenever David Finn’s lighting illuminated the section where a scene was happening, the rest of the stage were left in the dark!

It was even darker throughout the second act, where a lot of time the backdrop was video of a starry night to match the nocturnal quality of the music. I couldn’t help thinking this production might be one of the darkest productions I had ever seen on War Memorial stage!

In general, Pulitzer directed the singers reasonably well, and on that Opening Night there was very little, if any, sense of tentativeness that often plagued such events. Other than the nightmarish Caesar’s ascension scene mentioned above, I wished that Pulitzer presented The Battle of Actium scene more than just something resembled marching band formation, particularly as Adams’ score for this moment was exceptionally glorious!

I also felt ambivalent towards the use of multiple black-and-white historic newsreels throughout; while I understood the intention, they only confused the audience already struggling to understand the opera and its multifold characters!

If the production proved to be problematic in some aspects, I was happy to report that the music-making on the Opening Night was of the highest level. Music Director Eun Sun Kim, leading her first contemporary opera, brought power and vigor in her reading of Adams’ score, especially during the many march-like passages, and invoked sad moody nights leading to the tragedies. Kim was additionally sensitive to the needs of her singers, resulting in perfect balance between orchestra and the cast, without one overpowering the other.

What a lovely cast that SF Opera assembled for this performance; many of which had worked closely with Adams in the past! (Gerald Finley originated the role of J. Robert Oppenheimer in Doctor Atomic, while Paul Appleby debuted Joe Cannon in Girls of Golden West.)

Adams originally wrote the role for his frequent collaborator Julia Bullock, who unfortunately had to pull out from this production last May due to her pregnancy with her first child. Egypt-born and New Zealand-raised Amina Edris, a former Adler fellow, stepped in and on Saturday night, she dazzled the audience with her wholesome portrayal of the Queen of Egypt. T

here was a steely quality in Edris’ instrument that brought grit and determination into her interpretation (even if her very top notes might sound rather metallic at times), and she immersed herself fully in the ever-changing parade of Cleopatra’s emotions. Not to mention, she looked absolutely stunning in those flamorous dresses!!

Finley brought decades of working relationship with Adams in his ease of singing Adams’ melody for Antony; every line was beautifully executed, every nuance explored. With his booming voice and command of stage, he gave Antony a very regal and dignified presence, a real man torn between political aspirations and love. It was unfortunate that Antony’s demise was displayed in a rather trivial way, as Finley really gave heart and soul to the character.

Appleby’s bright tenor voice provided a youthful reading to Octavian, and he imbued his character with an almost childlike sensitivity in the beginning of the opera that turned Octavian into some kind of spoiled brat. However, Appleby fully came into his own in the second act, where he unleashed an evil persona as Caesar (and stamina too, as he had to sing above a blasting orchestra and chorus for an extended period of time) hellbent to conquer the world!

The rest of the comprimario roles was filled with excellent voices that brought up the drama. Debuting Taylor Raven was ravishing as Charmian, Cleopatra’s attendant, and mezzo Elizabeth DeShong brought a much-needed contrast in her depiction of Octavia, Octavian’s sister (who got entangled in the politics) with her low notes.

Alfred Walker provided some momentary laughs with his wise-cracking comments as Enobarbus (Antony’s/Cleopatra’s lieutenant, still not sure which). Hadleigh Adams presented a sarcastic Agrippa with his evil advice to Octavian, and Bay Area veteran Philip Skinner was seriously underutilized as the Lepidus (the other Triumvir besides Antony and Octavian).

Brenton Ryan took the thankless job being Eros, tortured by Cleopatra and ended up dead rather than killing his master Anthony. The SF Opera Chorus completed the cast with powerful depictions of the Egyptians in Act 1 and the Romans subsequently.

Here’s to San Francisco Opera for commissioning and presenting new works in the future, as our future is depended on it! The night before, during the Centennial Celebration Concert, General Director Matthew Shilvock announced that next season would feature three new works, including one by Kaija Saariaho (presumably Innocence) and one by Rhiannon Giddens (maybe Omar?)

Photos: Cory Weaver/San Francisco Opera

Comments