‘I want somehow to develop this world which is, on the one hand, full of recognisable human beings with all their flaws, and all their anxieties, loves and hatreds, but at the same time I want to deal with something which is epic, mythological and unexplained,” says Barrie Kosky in an interview included in the programme for his new production of Das Rheingold, the first instalment of a complete cycle of Wagner’s Ring for the Royal Opera, due to be completed by 2027.

What Kosky’s Rheingold offers is an uncluttered presentation of the narrative, blessedly free of philosophical theorising, but with a message that is clear from the start. The charred, fallen remains of the world ash tree, which binds the universe together in Wagner’s mythology, dominates the stage in Rufus Didwiszus’s set, and before even the famous, unfathomably deep pedal E flat has been sounded in the orchestra to conjure that operatic world into existence, the extremely old, extremely frail figure of Erda, the earth goddess, is seen dragging herself across the stage, as if trying to comprehend what has happened to the world for which she had cared for so long.

Played with compelling poise and presence by the actor Rose Knox-Peebles, and later briefly given creamy voice from offstage by Wiebke Lehmkuhl, Erda is an ever-present observer of everything that follows, all of it perhaps conjured out of her memories or dreams. The Rhinemaidens (Katharina Konradi, Niamh O’Sullivan and Marvic Monreal) play kiss-chase around the fallen tree, teasing and humiliating Christopher Purves’s easily seduced Alberich before he steals their gold, while Wotan, Fricka and their relatives are first seen picnicking in front of the tree like an Edwardian family, complete with riding boots, headscarves and croquet mallets; costumes (by Victoria Behr) are unspecifically contemporary throughout.

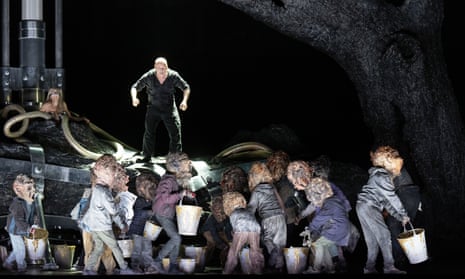

In Nibelheim, Alberich’s workers, played by children wearing a variety of curiously deformed heads, collect the “gold” in liquid form as it gushes from the ash tree, apparently extracted by a contraption somehow connected to Erda. The Tarnhelm transformations, through which Alberich torments Mime (Brenton Ryan) and is then tricked and captured by Wotan and Loge are rather underplayed, though the ripping of the ring from Alberich’s finger is bloodily graphic.

As per Kosky’s credo, all these characters are clearly defined in terms of human qualities that are easily recognisable, whether it’s Christopher Maltman’s bumptious, bullying Wotan, Marina Prudenskaya’s haughty, coquettish Fricka, Sean Panikkar’s hyperactive, scene-stealing Loge, or the giants Fasolt and Fafner, played by In Sung Sim and Solomon Howard as a couple of wide-boy builders, who are likely to retile your roof whether it’s needed or not.

The production is careful to avoid anything too reductive or stereotypical, though it’s only in the final scene, with its glittering, stage-filling depiction of the rainbow bridge to Valhalla, that there’s any sense of the majestic or the mythic. Musically, though, it has all the right sense of scale and weight throughout – Antonio Pappano’s conducting always has the measure of both the score’s grandeur and its intimacy, and vocally the cast has no weak links. Maltman’s voice seems strikingly darker than last I heard it, Purves is as compelling a communicator as ever, each morsel of text crystal clear, and Panikkar makes every cynical aside count. Above all, though, this is a Rheingold that really makes you want to find out what is going to happen next.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion