© Marc Brenner

© Marc Brenner

Composed in 1751, Handel’s Jephtha is based on the story from Judges XI and George Buchanan’s 1554 play Jephthes, sive Votum. It sees the Israelite Jephtha triumph in battle over the Ammonites, but then face the most dreadful situation. This is because he had vowed that if he were victorious he would sacrifice the first living creature he saw on his return, and this turns out to be his daughter Iphis. To make the work acceptable to an eighteenth century audience, Handel’s librettist Thomas Morell modified the ending so that an Angel saves Iphis from death, declaring that she is ‘only’ required to live out her days as a virgin in the service of God. However, Jephtha still suffers the utmost agony as a result of his rash promise because the ‘reprieve’ only comes at the end, and, in this staging at least, hardly leads to a neat conclusion.

Jephtha is Handel’s final oratorio, and as he wrote it he was increasingly troubled by his gradual loss of sight. The work premiered at the Covent Garden Theatre on 26 February 1752, but this new production by the Royal Opera’s Director of Opera Oliver Mears represents the first time that it has been seen at the venue since then. While it is an oratorio that more readily lends itself to being staged than some, there are always challenges when applying the full production treatment to such a work. These include the facts that the score does not include music to aid the transition from one scene to the next as it might in an opera, and that the chorus cannot stand in neat rows for the entire performance. Mears and movement director Anna Morrissey handle both issues well by finding smooth and unobtrusive ways of removing chorus members from the stage and reintroducing them, as changes from one setting to the next are always swift and inconspicuous.

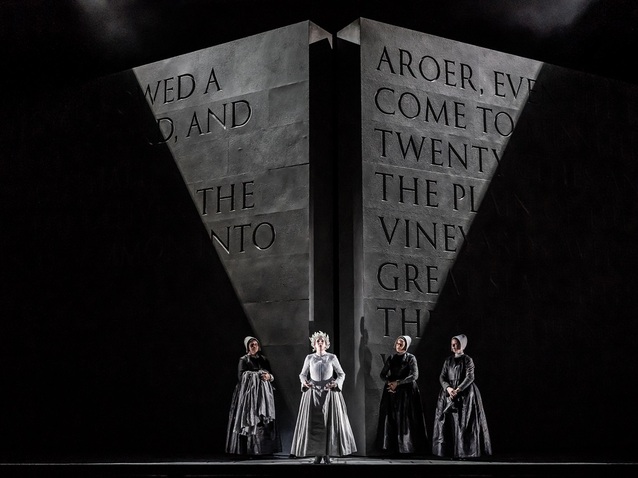

The overall tone that is generated by the aesthetic would appear to be more important to Mears than the context for the action, which feels quite unspecific. Monochrome shades prevail in Simon Lima Holdsworth’s set as two or three enormous stone tablets dominate the stage, and are moved into different positions for the various scenes. The Israelites’ costumes, courtesy of Ilona Karas, have a somewhat puritanical air, so that when we see them standing before the stake on which Iphis is about to be burnt the thought of seventeenth century Massachusetts witch hunts arises. In order to provide the most obvious of contrasts, the Ammonites are shown in bright colours, and during the Prelude they indulge in a hedonistic feast at which priceless works of art are slashed.

Allan Clayton (Jephtha), Jennifer France (Iphis) ROH Jephtha © Marc Brenner

The presentation is certainly thoughtful as Jephtha sings ‘Deeper, and deeper still, thy goodness, child’ entirely alone before the chorus is suddenly revealed through the parting of walls for ‘How dark, O Lord, are Thy decrees’. Its members remain in shadow as they sing it, thus allowing us to focus on Jephtha’s reaction to the large image of an eye gazing at him. This reveals how he feels he has no means of escaping the vow that he made, while the eye could also be the sun of which he sings at the start of Act III.

All this said, there are scenes when, despite there being appropriate levels of movement and interaction, one is left wondering what more is being introduced with this staging than would have been achieved without it. After all, presenting the piece in its original oratorio form does not prevent the soloists from being expressive when they sing. For significant periods the atmosphere seems quite subdued, while some of the attempts to inject more action, such as demons rising from beneath Jephtha and his wife Storgè’s bed to depict her nightmare, feel just a little comical.

There are, however, some scenes that are particularly effective. The end of Act I packs a punch as Jephtha attempts simultaneously to control and urge the Israelites on, with the mass of weapons that they brandish casting interesting shadows. When Jephtha sees Iphis on his return from battle, she is joined by many other figures playing her, highlighting how he cannot avoid seeing her. Lighting designer Fabiana Piccioli ensures that as they move around, they cast both small and large shadows on the huge tablets, depending on their position, and the effect is especially strong when figures and thus their shadows cross.

Jennifer France (Iphis) ROH Jephtha © Marc Brenner-5510

As a rule, the number of scenes that are effective grows as the evening progresses, with the consequence that the overall pace seems to accelerate. The irony is that while the change to the ending that Morell introduced was to solve a problem for eighteenth century audiences, his new one is problematic for us today because it is committing a woman to a life that she has no choice over. This production meets the difficulty head on and ‘solves’ it in a highly innovative way. It would be wrong to give the ending that is opted for away, but the combination of the strong choice and the actual execution makes for an extremely impactful close to the evening.

Baroque specialist Laurence Cummings elicits a highly accomplished sound from the Orchestra of the Royal Opera House, while the cast is superb. Brindley Sherratt brings his commanding bass to the fore as Jephtha’s half-brother Zebul, while mezzo-soprano Alice Coote is a class act as Storgé. Jennifer France reveals a notably persuasive soprano as Iphis, while Cameron Shahbazi displays an exceptionally pleasing countertenor as her lover Hamor, and treble Ivo Clark (who shares his role with Kaelan O'Sullivan) produces an exquisite sound as the Angel. The real standout performance, however, comes from Allan Clayton in the title role. It is not only the strength of his tenor that comes to the fore, but also the manner in which he so completely embodies the part so that once he is faced with the dilemma of killing his own daughter his anguish consumes him in every conceivable way.

By Sam Smith

Jephtha | 8 - 24 November 2023 | Royal Opera House, Covent Garden

the 10 of November, 2023 | Print

Comments