Anish Kapoor has been getting quite a bit of flak for designing the sets for a new production of Tristan and Isolde, Wagner’s great opera about two passionately deranged lovers. “Wagner was antisemitic and I’m Jewish,” he says. “And many of my Jewish relatives and friends say: ‘How can you?’ Honestly, in the end, one somehow has to put that aside.”

How can he? Well, Kapoor can because, in part, the dead German bigot had a similar artistic temperament to the Indian-born British artist. “I take the view that there are emotional states that Wagner touches that nobody else touches. In the end, who cares if the artist is a nice person?”

Kapoor, born in Bombay in 1954 to a Jewish mother and a Hindu father, has become – echoing Daniel Barenboim – a Jewish artist for whom interpreting the antisemitic composer’s music has become an irresistible temptation. He made sets for Pierre Audi’s 2012 production of Parsifal in Amsterdam – and has now collaborated with Daniel Kramer on English National Opera’s first new Tristan for two decades.

For years, Kapoor listened to Wagner in his studio. “There’s something about the sheer drama of Wagner that felt right,” he says. It’s easy to imagine Kapoor listening to Der Ring des Niebelungen and being inspired to make such vast, Wagnerian-scale works as Marsyas, the 150-metre long, 10-storey high sculpture he created for Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall in 2002. But those days of epic musical inspiration are behind him. “I work in silence now.”

In a recent blog, Kapoor quoted Marcel Duchamp, who saw the artist as “a mediumistic being who, from the labyrinth beyond time and space, seeks his way out to a clearing”. Kapoor sees himself as just such a seer: a Wagner of the visual, revealing truths beyond the quotidian. We are chatting at the Coliseum, ENO’s London HQ, as Kapoor takes a break from finessing the production’s lighting. He is just back from opening two shows in New York and a retrospective in Mexico so successful that there are two-hour queues to see it. Meanwhile, back in London, his ArcelorMittal Orbit tower in the Olympic Park has been fitted with the world’s longest tunnel slide, 178 metres in length. It opens this month and, he says, 9,000 people have already booked a ride.

He won’t be among them (it’s not his kind of thing). Instead, he’s getting his kicks from interpreting Wagner. Two things made him accept the invitation to work on Tristan: religion and sex. Both are abiding concerns in Kapoor’s art. “My sculptures are deeply rooted in orientating the body, in putting one in a frame of a certain kind of looking and thinking. I think that’s religious. It’s often processional and intentionally philosophical, too. That’s what Wagner is about, too.”

And sex? “Tristan is all about things I keep coming back to in my work – male and female, sexuality, oppositeness. Tristan is male-male and Isolde is a rather dangerous female. She’s no wallflower. This is a tussle. Whose power is stronger – his or hers? In the end, probably hers.”

The inspiration for Kapoor’s sets came a couple of years ago, when he went to the Royal Opera’s acclaimed revival of Christof Loy’s 2009 Tristan. “I got my sketchbook out. The guy next to me got so upset. I hope he reads this piece. He said: ‘Horrible noise of scribbling! You can’t do that – I paid for my ticket!’ I thought: ‘Fuck off.’ I carried on sketching.” It’s a lovely thought: irritating Covent Garden opera-goers so that he can design a production for London’s rival house.

“That production made me think – how do you make two perfectly ordinary human beings superhuman? They could all be on stilts. Or one can put them in situations which speak to their heroic nature. That’s what I’ve tried to do. That is what making a set for opera is all about – encouraging one to suspend disbelief, or rather encouraging belief in the unbelievable.”

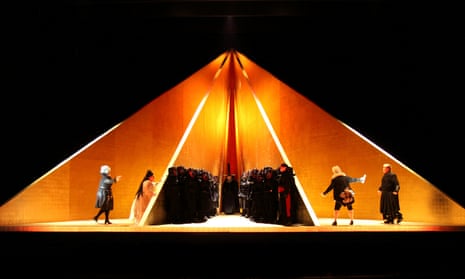

After the interview, I watch a run-through of the first act, in which the protagonists sail to Cornwall. Kapoor elegantly divides the stage with four huge, sail-like triangles whose apexes meet, as if at the top of the ship’s mast. The result is three sharply defined spaces. The left is occupied by Isolde, the right by Tristan, and in the middle is a frequently unlit void – another one of those abysses that crop up repeatedly his work.

But it’s the lighting effects that are really striking. Isolde’s grey ballgown shimmers in lilacs and purples, reinforced by a splash of purple across the stage. “Colour gives a quantity to an object which is illusionistic,” says Kapoor. “That’s why I’m loving working with light here.” He thinks such transitory effects embellish the Wagner he loves – that virtuoso of transitional music, that musician of mutability.

Strikingly, Kapoor worked on this opera by a Jew hater after experiencing antisemitic hatred for Dirty Corner, a vast steel funnel made for the gardens of Versailles last year, a sculpture he described as “the vagina of the queen” taking power. “I didn’t mean to cause offence,” he says, “but offence was taken because it’s feminine, vaginal.”

He removed some graffiti, but then more appeared. “The second time it was antisemitic and unbearable,” he says. The sculpture and surrounding rocks were sprayed with such phrases as “SS blood sacrifice” and “the second RAPE of the nation by DEVIANT JEWISH activism”. Kapoor decided to take a stand. “I said I would leave it there as part of the work.”

The artist was then taken to court by Fabien Bouglé, a local councillor, for displaying antisemitic material. “I thought: ‘Fuck ’em. I’m not going to change this.’ So I covered the bits of graffiti that were prominent with gold leaf – gold leaf being the stuff of Versailles. Just enough so it wouldn’t land me in jail.”

And so, until November last year, the gardens had an ugly reminder of French civilisation’s barbaric underside. “I’m not looking for controversies,” says Kapoor. “But if that’s where it goes, I’ll follow it. That’s what you do in the studio: something accidental happens and you follow it. Life threw something deeply ugly, but maybe it was ugliness that needed to be followed. Art can’t always be about creating beauty.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion