Shostakovich’s The Nose, composed in his early 20s, is a fabulously exaggerated, cacophonous, insanely over-the-top satirical fantasy written by a young man wholly and exuberantly indulging in his role as enfant terrible. The story comes from Gogol, whose masterly output of short stories can be crudely divided into rural and urban. In his collection of Ukrainian tales, Evenings on a Farm near Dikanka, he used a romanticised background of village life to tell a series of vivid stories richly peopled with devils, rusalki (mermaids) and ghosts set against a marvellous gallery of village characters: grumpy elders, strutting peasant lads and simpering dark-eyed maidens. This colourful collection of stories would inspire several operas by Rimsky-Korsakov and Tchaikovsky, and is a close cousin of the Jewish folktales from the shtetl that were lovingly recorded by Sholem Aleichem.

Gogol’s “urban” works display a similar technique and characters but in a very different context: St Petersburg. The city was one of the early examples of the Russian weakness for the command economy, Tsar Peter’s equivalent of a “five-year plan”. Seeking an outlet to the west (via the Baltic) and a symbolic separation from the traditionalist stronghold of Moscow, he ordered a city built in a swamp beside the river Neva. Despite its buildings of unparalleled magnificence, St Petersburg always had the whiff of fakery about it, and when the freezing fog welled up from the Neva one might imagine that all these apparently solid palaces could in a moment slide into the mud and vanish. This was the city’s phantasmagorical underbelly, which Gogol chose to explore.

However, phantasmagoria was not the end but the means of his deftly constructed novellas. The goal was to satirise St Petersburg’s expanding nouveau riche society – an invented society to people its invented streets. As in most nouveau riche societies, people took themselves and their new positions very seriously. Titles and uniforms were all-important, and a vastly overblown bureaucracy exerted a malignant stranglehold based on rank and procedure. Gogol used the absurd to puncture this pomposity and pretension.

In his story “The Overcoat” he tells the tragic tale of the unspeakably poor and dull clerk Akaky Bashmachkin (kaka = shit, bashmak = shoe, so “shitty shoe”), who to his horror discovers that he needs a new overcoat. He scrapes and saves and fills his life with dreams of this garment, and when he finally achieves its purchase, it is a moment of redemptive ecstasy. A short while later he is robbed, the overcoat torn from his back, and he dies, heart-broken.

So far, this is a realist picture of grinding urban poverty. Now, however, a mysterious corpse starts to haunt the banks of the Neva, tearing the coats off the backs of prosperous citizens. Finally, the “significant personage” who had treated Akaky with contempt when he came to seek redress for his robbery is himself robbed by this ghoul, and from that terrifying moment resolves to become a better man. The phantasmagorical brings about a moral dimension.

Elements from this story found their way into Shostakovich’s opera alongside Gogol’s “The Nose”, in which a “councillor” (a civil service rank) wakes up to discover that his nose has absconded. Suffering greatly from this literal loss of face, he is further horrified to discover that his nose is calmly walking the streets dressed in a uniform superior to his own, and is greeted on all sides with appropriate respect. In the end, a police inspector returns the nose to its owner, who is finally able to rejoin the promenading gentry on Nevsky Prospect, restored to his rightful status.

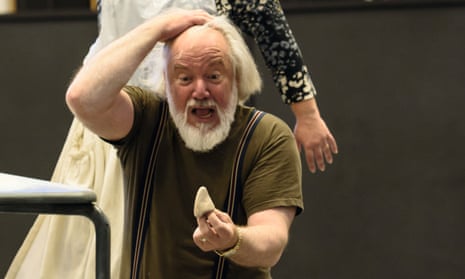

Between these seemingly thin parameters, there lies an ocean of excess, performed by a cast with more than 80 named roles. Translating this mayhem into English was great fun, and the style of the work avoids many of the technical problems associated with other opera libretti, such as formal rhyme schemes. Also, since the musical style is brutal and utilitarian rather than mellifluous, there is not the same problem about the sonority of the language as would be the case with Eugene Onegin, for instance.

It is of course unusual for the Royal Opera to perform in translation, but there is no doubt that immediacy of communication is valuable for a zany comedy of this kind. Even the surtitles are appropriate, as it was Shostakovich’s stints as a pianist accompanying silent films that gave him a taste for high-energy pranks.

He wrote The Nose from the unguarded standpoint of a young composer using his entire box of tricks at a time when the liberated Russian intelligentsia had free rein to experiment and revel in the avant garde. The first Stalinist crackdown was still around the corner. The result is almost a catalogue of all the devices and gestures that would become standard practice for mid-to‑late 20th-century modernist iconoclasm. The orchestra is encouraged at one point to shout out remarks to the singers, there is an ensemble entirely consisting of percussion, a group of 11 policemen sing a lugubrious song about tobacco and then gang-rape a screaming pie seller, a sheikh passes by and comments on the fascinating case of the disappearing nose, and a cynical doctor advises the victim to have his nose preserved in formaldehyde and sold as a curiosity. Everything is faster, slower, longer, louder or, especially in the case of the screaming police inspector, higher than you might have thought possible. The music imitates farts, burps, the sound of a nose falling into a tin basin, as well as ecstatic voices in the Kazan Cathedral.

At the end of Gogol’s story, he invites speculation on the value to a national culture of telling such a tale. A note in the full score suggests such a discussion could take place towards the end of the opera. No text is provided, but it is all too easy to imagine some Hooray Henry harrumphing from the stalls: “One of the rare cases when the opera was even sillier than the production!”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion