Death in Venice is Benjamin Britten’s final opera, written when he was ill with the heart condition that would kill him three years after its premiere at Snape Maltings in 1973. “It’s a deeply personal and intimate piece. Britten wasn’t a well man at the time of its composition, and he didn’t know how much music he had left in him. The epilogue, the last 20 bars, is the most serene and profound music he ever wrote. It’s Britten’s requiem for not only himself, but for his life partner, Peter Pears,” says Leo Hussain, conducting this production for Welsh National Opera – the first time the company have staged the work.

Mark Le Brocq sings Aschenbach, the role Britten wrote for Pears. The libretto adapts Thomas Mann’s 1912 novella and tells of an ageing writer suffering from creative block who goes south to Venice in search of inspiration. There he encounters and is transfixed by a beautiful young Polish boy, Tadzio. Venice meanwhile is in the grip of cholera and the city empties around Aschenbach as tourists flee the infected city. “It’s an exploration of the idea of beauty and passion and the intellectual versus the physical side of beauty and Aschenbach’s struggle with what he calls the abyss – temptation,” says Le Brocq. “Of course, he never even talks to the boy let alone does anything else; he is sort of destroyed by the fact that he can’t express how he feels outwardly, or even inwardly.”

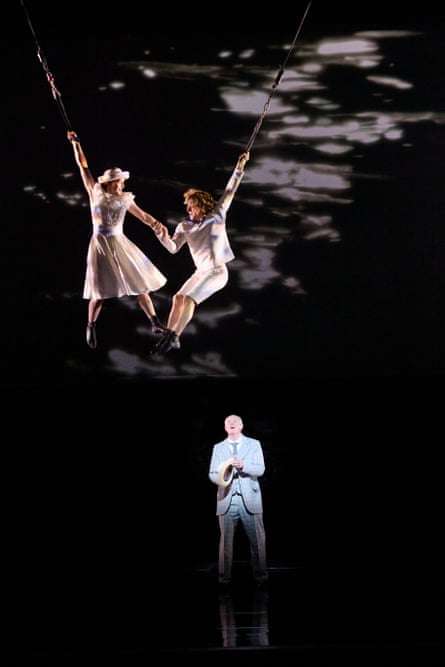

“I had always found the opera tricky,” says Le Brocq. “There’s some extraordinary music but a lot of it is also just one chap soliloquising about stuff that is quite dense and hard to understand, which is why it’s such a brilliant decision to use the circus performers.”

Tadzio is played by 21-year-old aerialist Antony César

Roderick Williams (below) plays seven different characters, from a travelling player and a barber to an “elderly fop” and a mysterious and truculent gondolier. “I’m having a lot of fun!”

Roderick Williams in four of his seven roles: (top) the leader of the players; (middle, in red) the voice of Dionysus; (middle, dark suit) the hotel manager and (bottom, not in costume) the gondolier

Death in Venice is a profoundly ambiguous text, says Williams. “It’s wonderful. Opera is really good at primary colours – he loves her, she hates him – but I sing so few ambiguous texts. When I listen to Britten’s opera in general, and this one in particular, I’m astonished to find that I come away every time thinking, ‘that was beautiful, but also WTF? What just happened? What am I meant to take from this?’”

Director Olivia Fuchs with stage manager Jenni Price (centre), clarinettist William Knight (left), conductor Leo Hussain (right)

“Designer Nicola Turner and I were here in Cardiff working on The Makropulos Affair when we went to see NoFit State Circus one evening. It was shortly after that we were offered this production, and I thought straight away that we needed Tadzio to be an aerialist,” says Fuchs. “Britten wrote him, and his family, to be non-speaking characters and they’re usually ballet dancers. I wanted to find a different dimension, where you come off the floor, literally, and go into a different world. The opera is very much about imagination, a lot of it takes place in Aschenbach’s head.

“The wonderful thing about NoFit State and artistic director Firenza Guidi is that their kind of circus is not about tricks. They tell stories, cross boundaries and work through the body,” adds Fuchs. “They ask questions about gender, sexuality and marginalisation.”

“It’s incredible to see an opera – and I think Olivia has been visionary in this – where not only do we address Aschenbach’s hidden dark side but we are able to constantly ask questions about what is desire, what is beauty, who is woman, who is man,” says Guidi. The five circus performers include a transgender woman (Diana Salles, who plays the mother) and Riccardo Saggese as the governess as well as Tadzio’s friend.

“Death in Venice is so different to Britten’s other operas. It can seem dry and not immediately accessible,” says Hussain. The score is very much inspired by gamelan music. There’s a huge percussion section including marimba, a wind machine, crotales, Chinese drums. “The soundworld that represents the boy, the erotic and the exotic is very esoteric, very ‘other’”, says Hussain. “It contrasts with the more conventional western European orchestral world which represents Aschenbach. The two worlds only mesh at the very close of the opera.”

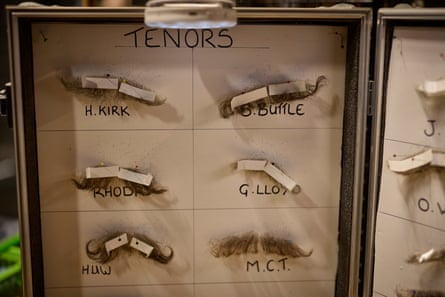

Above, top, the women of the chorus stand in the wings to sing “Ad-ziù” – a form of Tadzio’s name – off stage at key moments in both Acts. The 33-strong chorus have up to eight or – for some – even nine, costume changes with different hats, wigs, hairpieces, masks and props for each scene. The moustaches are applied with toupee tape. Below, aerialist Riccardo has his wig fitted to play the Polish family’s governess, a non-speaking role.

Aerialist Riccardo Saggese with stage manager Jenni Price.

Italian-born Saggese is 28. “I’d seen the Visconti film but I’d never heard of Britten or of this opera before this.” What did he think when the collaboration was first suggested? “Brilliant! Yes please!”

It’s been challenging, he says, coming from two such completely different worlds, but hugely rewarding. “It’s amazing to work with people who use their voices in such an extraordinary way. We’ve been amazed by the singers. There’s so many points in the show where the singers are singing next to us and their energy gives us the energy we need.”

Left: prop strawberries – ripe and healthy in the first act, dusty and diseased in the second; right: touring wardrobe technician Thomas-Huw Hopkins adjusts a costume backstage.

Antony César (Tadzio) and Riccardo Saggese

“The music is the music and everything we do movement-wise has to fit into that,” says Fuchs. “My performers have never worked with opera before,” adds Guidi. “The music does impose a straightjacket on them that they never usually have, but we’re relishing the challenge.”

Alexander Chance (below) is making his debut in a role that his father, countertenor Michael Chance, also sung 35 years ago. “The Voice of Apollo was originally written to be sung off stage. My dad, in a production for Glyndebourne Touring Opera in 1989, was the first person to sing it on stage, since when directors have mostly staged it that way too. I’m delighted – not least as I get to wear this fabulous gold suit!”

Countertenor Alexander Chance sings the Voice of Apollo

For Britten the countertenor voice represents the otherworldly, the mystical and magical, says Chance – it’s also the voice of Oberon in his Midsummer Night’s Dream. “I’m only on for two scenes but I have wonderful music to sing. Britten’s music is intoxicating. It gets into your soul.”

“My dad and I joke that it’s the family business – some families are footballers or plumbers, we’re countertenors. I did try being a bass when I was at school but singing countertenor always felt most natural.”

The whole piece is very much about the Apollonian and Dionysian principles (roughly: order, intellect, harmony, versus chaos, passion, intoxication). “And in a way we’ve brought these two together,” says Fuchs. “The music is ordered and precise, and then there’s the chaos and craziness of the circus. The production has been about finding the balancing act between these two worlds. There’s been an exchange of skills and cultures. It’s been really exciting. Each world has been excited by and learnt from the other.”