Renée Fleming Was Magnificent in ‘A Streetcar Named Desire,’

But the Play Put to Music Raises Doubts.

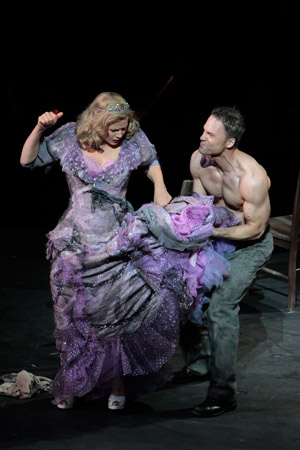

Renée Fleming as Blanche,

Ryan McKinny as Stanley.

(Photo: Robert Millard)

TENNESSEE WILLIAMS

‘A STREETCAR NAMED DESIRE’

ANDRÉ PREVIN, COMPOSER

PHILIP LITTELL, LIBRETTO

LOS ANGELES OPERA

DOROTHY CHANDLER PAVILION

SEEN MAY 24, 2014

By Carol Jean Delmar

Opera Theater Ink

I have so many thoughts about LA Opera’s production of Tennessee Williams’ “A Streetcar Named Desire” — adapted to music by André Previn — that I will start with the one positive element that is not debatable: Soprano Renée Fleming was magnificent. Her voice glistened up the scale with shimmering tonality and luminescent pianissimos. Her Blanche DuBois was graceful, flirtatious, fragile, frightened and devastating.

The complete cast was excellent. Ryan McKinny made the role of Stanley Kowalski his own so that we did not compare him to Marlon Brando in the film. Whether an acting Stanley or a singing Stanley, McKinny was as good a Stanley as Stanleys get, and I rate him among the best. He displayed an animalistic, macho, virile physique coupled with a desperate organic need for his wife, Stella. He was able to mesh the music with the words so that all we saw was Stanley. His voice was almost incidental except that the sound was plush and interconnected with his being so that the sound and the being became one.

As for the story: Blanche DuBois visits her sister, Stella, in New Orleans because she has lost the family home and her job as a school teacher. She meets Stella’s husband, Stanley Kowalski, and the two immediately develop a disliking for each other. He is too crude and earthy for her. She is too phony and full of feminine airs for him. And Stella placates them both.

Blanche meets and hopes to marry one of Stanley’s poker buddies, Mitch, but the idea is shattered when Stanley shares the news with Mitch that Blanche was forced to leave the town of Laurel due to her immoral behavior with young men.

After Stanley takes a very pregnant Stella to the hospital, he returns home in the evening, finds himself alone with Blanche, and rapes her. Stella’s unwillingness to accept Blanche’s story leads Blanche into an abyss of despair. The inability of the three to live together finally incites Stella to have Blanche committed: a tragic fate for a woman unable to survive in an unkind world.

“A Streetcar Named Desire” is a classic play by Tennessee Williams. It is one of my favorite plays. The writing is poetic. In fact, if executed by a fine cast, the words become music. It is therefore a terrible burden on a composer to attempt to turn what is already music into music. I am surprised that the estate of Tennessee Williams authorized the endeavor. Yet although the resulting opera has merit, there is only one great “Streetcar Named Desire,” and it is the play by Tennessee Williams.

I believe that new operas can be more successful if the stories haven’t been told before so that the operas can stand on their own without comparison. The “Streetcar” opera follows the play’s story and includes Mr. Williams’ words.

Much like a singer, an actor’s spoken voice becomes an instrument of sound. It is the variation of color in the voice, for example, in Blanche’s Scene 6 monologue, that can bring an audience to tears. The actress can virtually become the character of Blanche as she tells Mitch the story of her gentle homosexual ex-husband who killed himself as a result of her unkind scrutiny, for which she feels responsible. The poetic words of the monologue don’t need music. The music in Previn’s score during the monologue only detracted from the monologue’s essence. It would take quite a composer to outdo Williams on Williams.

Although the singers performed eloquently, they could not reach us emotionally the way the great actors who have portrayed the same characters in the play have. Yet strangely, these singers were so expressive that at times they almost did — in spite of having to wade through the music to do it.

Tenor Anthony Dean Griffey brought more dimensions to Mitch than I have ever seen. Although his voice was on occasion slightly guttural on the vowels in words like “love,” for example, for the most part, his sound was up front and out in the hall much like his performance was. Raised in a crude environment, his Mitch remained the considerate son of an aged mother whose sympathetic, good-natured side mixed with his moral upbringing to make it impossible for him to accept Blanche as his wife. At the end of the opera, however, when Blanche was forced to leave her surroundings and was being led into her nightmarish hell, Mitch felt guilt and sorrow for Blanche because he had played a role in her disintegration. It was this empathy that Mitch displayed toward Blanche which was gratifying to watch and more evident in this opera than in the play due to Griffey’s sensitive portrayal.

Soprano Stacey Tappan sang Stella with ease and displayed a strong character with a freeness and willingness to execute any movement that would further the action. She made the audience understand her plight.

Mezzo-soprano Victoria Livengood as Eunice was the character actor in this production. Although her voice had some noticeable vibrato, it boomed out to the rafters, and every time she came onstage, the energy level rose 100 degrees and we loved her.

The doctor, Robert Shampain, and the nurse, Cynthia Marty, somehow seemed visually miscast. He was somehow too slight of build or youthful to so quickly lure Blanche into his good graces, and the nurse didn’t exude enough intimidating authority. Cullen Gandy as the collector and Blanche’s ex-husband was perfect.

Brad Dalton’s direction was specific, detailed and creative. The minimalistic set included chairs, a table and a bed, with the orchestra placed upstage behind the singers, dynamically conducted by the young Evan Rogister.

This production from Lyric Opera of Chicago was cost-effective and diverged from the initial production, which had a traditional set and premiered in 1998 at the San Francisco Opera.

The Stanley replicas who doubled as Stanley’s poker buddies began the action as the audience was being seated and during intermissions. There was no curtain. Only effective lighting brought us in and out of the action.

As for André Previn’s score, it seemed like a work in progress. I say that because I actually wanted to leave at the conclusion of Act 2 because I couldn’t weave the music with the characterizations to realize a work of art that was equal to or superior to the Williams play. The orchestration seemed like background music for the singers who were simply speaking on notes. Speech level singing came to mind, not really recitative, even though the performers were truly singing dialogue on notes, and sometimes the dialogue sounded mundane. Of course I wasn’t sitting with the play and libretto in front of me. But because I had put some of the dialogue to memory, I knew that the libretto followed the text of the play with some liberal variation.

The orchestral score seemed superior to the vocal score because at times, the two sopranos sounded like tweety birds due to the high tessitura which sometimes seemed stuck on one plane so that the vocal sound almost became annoying. I couldn’t even tell if the singers had quality voices even though I knew that they did. The composition just didn’t allow me to make the determination.

When Ryan McKinny was dramatic, his bass-baritone carried the drama. But Renée Fleming is a soprano known for her lyricism, and the high lyrical sound just didn’t work well with heightened hammered drama. It wasn’t her fault, though. She was wonderful.

Modern operas are always filled with atonal dissonance, and this opera is no exception. But the dissonance in “Streetcar” seems amazingly appropriate. It is blended well with a bluesy jazzy feel and music reminiscent of Richard Strauss, George Gershwin, Benjamin Britten, Alban Berg and Leonard Bernstein’s “Westside Story.” With strings, woodwinds and a brassy quality heavy on the trumpet and trombone, the orchestration sounds like 1940’s-era New Orleans mood music with voices imposed on top of it.

Renée Fleming

Before writing more about Miss Fleming, it was necessary for me to explain why the opera seems like a work in progress and doesn’t reach its potential until Act 3.

Fleming was marvelous throughout, but she was still singing like an opera singer performing for an audience — unable to touch us emotionally like an actor would until Act 3. This was due to the vocal score which fits her tessitura, not to her performance. Her glimmering voice was mesmerizing with some rich mezzo-like accents. But none of the music, not even the arias of the other characters, enabled the audience to stop, as in Mozart, and think: “Wow, that was glorious.”

For “Streetcar” to succeed as an opera, the music must enhance the telling of the story or should add something new to Williams’ text. If Williams’ words are better said by an actor in the play than sung, and if the music does not add anything unique to the opera genre, then the opera cannot work. That is why a poetic classic like “A Streetcar Named Desire” is difficult to adapt as an opera.

Finally in Act 3, the opera came into its own. During the first two acts, I was envisioning Vivien Leigh, Ann-Margret and Jessica Lange as Blanche — especially Jessica Lange who created a multi-dimensional character with emotional depth and artistry.

But then in Act 3, the rape scene was musically charged and emotionally riveting. Both Blanche and Stanley were alive and real. And finally, finally Miss Fleming sang “I Can Smell the Sea Air,” and the sound was gorgeous. Previn had given her a memorable aria that allowed the audience to hear the beauty of her resonant sound.

So to me, this opera is a work in progress because to make it equivalent to Williams’ poetic play, the opera version of “Streetcar” should include more lush melodic harmonies on the level of Blanche’s last aria, which is competitive with the music of the great opera composers of the past. Although we may not have seen Blanche’s true madness, we saw her drifting off into an ethereal world where she was no longer in touch with reality.

When the nurse kept repeating, “These fingernails have to be trimmed,” I died a thousand deaths. And as Fleming sang, “Whoever you are, I have always depended on the kindness of strangers. Whoever you are . . . whoever you are” — Fleming finally became Blanche DuBois and reached us. She was magnificent. And that is when I realized that Williams, Previn and the librettist had finally created an opera.

Director: Brad Dalton

Conductor: Evan Rogister

Lighting Designer: Duane Schuler

Costume Designer: Johann Stegmeir

Production: Lyric Opera of Chicago

Costumes: Provided by Washington National Opera

and Lyric Opera of Chicago

Critic’s Note: In deference to the composer and librettist, I need to write that my review is a review of the opera as it is, not as it could have been or could be. I realize that many factors contribute to a final composition. With a classic play like Tennessee Williams’ “A Streetcar Named Desire,” when the words are music to begin with, it is difficult to insert the dialogue into the mouths of singers over an orchestration so that the words have the same impact they do in the play. Music has time signatures, and the length a note is held has an influence on the language. So if the word “perspiration” works in the play, for example, the same word held in the context of an operatic phrase could accentuate it quite differently so that it simply sounds out-of-place in the context of the opera. Alas, some of the words in the libretto sounded mundane with far too much focus on them.

Even translating an opera from one language to another is a cumbersome job because words and syllables do not always match the notes that must be sung. So attempting to match Tennessee Williams’ words with a score was no doubt a daunting compositional task for the composer and librettist.

I have read that the Williams estate had a permissions agreement to adapt the play to opera so that the opera would maintain the integrity of the play’s story and much of the text, which was adhered to by the producing company, the composer and the librettist. The conditions imposed on them therefore limited their creativity.

The opera would have been quite different with a libretto that did not have to follow the play’s text. It might have been less wordy, and the accents on the words might have been more adaptable to the singers’ voices. The text would not have been compared to the poetic dialogue of the play. And a better marriage between the libretto and the vocal and orchestral scores might have ensued. Even the breathing of the singers must be considered to create vocal lines that tell the story.

So although I wrote that sometimes it is better to write new operas with plots that have never been told before so that the new operas will not be compared with the originals, it works to utilize an already existing story, but without attempting to create a carbon copy of the original by simply transferring the words to the different genre. If the original genre was successful, the opera genre should not have to compete. Each work should stand on its own.

Therefore, the opera “A Streetcar Named Desire” is what it is, and I have reviewed it as such. Had Previn and librettist Philip Littell started with a totally clean canvas except for the story, the result might have been quite different.

However I am sure that both the estate and the composer and librettist were attempting to develop a work of art that the playwright would have approved of. Writers do not like their words altered. However in the case of opera, the writer or representative of the original work should have a knowledge of music to draw the most optimal parameters for the work being developed. If an opera is to be successful, there must be flexibility from genre to genre.

But by the same token, if the librettist is left to create his own dialogue and the play is as poetic as “Streetcar” — it seems futile to even try. How could any other words compete with those of Williams in the context of the same story?

So in essence, with “Streetcar,” it is probably impossible to please all the parties, so maybe it was an implausible idea on the part of the estate and the opera’s creative team to authorize the project in the first place.

However, if I didn’t know and love the play; if I hadn’t have put some of the dialogue to memory — I would have been very accepting of this opera. The singers were terrific actors with a superb director. Renée Fleming outdid herself vocally and physically, and even though she created a devastatingly tragic character, she seemed to love being on the stage throwing her all into the role just for us. She gave us a wonderful night at the theater to remember. So what could be wrong with that?

Renée Fleming Was Magnificent in ‘A Streetcar Named Desire,’

But the Play Put to Music Raises Doubts.

Renée Fleming as Blanche,

Ryan McKinny as Stanley.

(Photo: Robert Millard)

TENNESSEE WILLIAMS

‘A STREETCAR NAMED DESIRE’

ANDRÉ PREVIN, COMPOSER

PHILIP LITTELL, LIBRETTO

LOS ANGELES OPERA

DOROTHY CHANDLER PAVILION

SEEN MAY 24, 2014

By Carol Jean Delmar

Opera Theater Ink

I have so many thoughts about LA Opera’s production of Tennessee Williams’ “A Streetcar Named Desire” — adapted to music by André Previn — that I will start with the one positive element that is not debatable: Soprano Renée Fleming was magnificent. Her voice glistened up the scale with shimmering tonality and luminescent pianissimos. Her Blanche DuBois was graceful, flirtatious, fragile, frightened and devastating.

The complete cast was excellent. Ryan McKinny made the role of Stanley Kowalski his own so that we did not compare him to Marlon Brando in the film. Whether an acting Stanley or a singing Stanley, McKinny was as good a Stanley as Stanleys get, and I rate him among the best. He displayed an animalistic, macho, virile physique coupled with a desperate organic need for his wife, Stella. He was able to mesh the music with the words so that all we saw was Stanley. His voice was almost incidental except that the sound was plush and interconnected with his being so that the sound and the being became one.

As for the story: Blanche DuBois visits her sister, Stella, in New Orleans because she has lost the family home and her job as a school teacher. She meets Stella’s husband, Stanley Kowalski, and the two immediately develop a disliking for each other. He is too crude and earthy for her. She is too phony and full of feminine airs for him. And Stella placates them both.

Blanche meets and hopes to marry one of Stanley’s poker buddies, Mitch, but the idea is shattered when Stanley shares the news with Mitch that Blanche was forced to leave the town of Laurel due to her immoral behavior with young men.

After Stanley takes a very pregnant Stella to the hospital, he returns home in the evening, finds himself alone with Blanche, and rapes her. Stella’s unwillingness to accept Blanche’s story leads Blanche into an abyss of despair. The inability of the three to live together finally incites Stella to have Blanche committed: a tragic fate for a woman unable to survive in an unkind world.

“A Streetcar Named Desire” is a classic play by Tennessee Williams. It is one of my favorite plays. The writing is poetic. In fact, if executed by a fine cast, the words become music. It is therefore a terrible burden on a composer to attempt to turn what is already music into music. I am surprised that the estate of Tennessee Williams authorized the endeavor. Yet although the resulting opera has merit, there is only one great “Streetcar Named Desire,” and it is the play by Tennessee Williams.

I believe that new operas can be more successful if the stories haven’t been told before so that the operas can stand on their own without comparison. The “Streetcar” opera follows the play’s story and includes Mr. Williams’ words.

Much like a singer, an actor’s spoken voice becomes an instrument of sound. It is the variation of color in the voice, for example, in Blanche’s Scene 6 monologue, that can bring an audience to tears. The actress can virtually become the character of Blanche as she tells Mitch the story of her gentle homosexual ex-husband who killed himself as a result of her unkind scrutiny, for which she feels responsible. The poetic words of the monologue don’t need music. The music in Previn’s score during the monologue only detracted from the monologue’s essence. It would take quite a composer to outdo Williams on Williams.

Although the singers performed eloquently, they could not reach us emotionally the way the great actors who have portrayed the same characters in the play have. Yet strangely, these singers were so expressive that at times they almost did — in spite of having to wade through the music to do it.

Tenor Anthony Dean Griffey brought more dimensions to Mitch than I have ever seen. Although his voice was on occasion slightly guttural on the vowels in words like “love,” for example, for the most part, his sound was up front and out in the hall much like his performance was. Raised in a crude environment, his Mitch remained the considerate son of an aged mother whose sympathetic, good-natured side mixed with his moral upbringing to make it impossible for him to accept Blanche as his wife. At the end of the opera, however, when Blanche was forced to leave her surroundings and was being led into her nightmarish hell, Mitch felt guilt and sorrow for Blanche because he had played a role in her disintegration. It was this empathy that Mitch displayed toward Blanche which was gratifying to watch and more evident in this opera than in the play due to Griffey’s sensitive portrayal.

Soprano Stacey Tappan sang Stella with ease and displayed a strong character with a freeness and willingness to execute any movement that would further the action. She made the audience understand her plight.

Mezzo-soprano Victoria Livengood as Eunice was the character actor in this production. Although her voice had some noticeable vibrato, it boomed out to the rafters, and every time she came onstage, the energy level rose 100 degrees and we loved her.

The doctor, Robert Shampain, and the nurse, Cynthia Marty, somehow seemed visually miscast. He was somehow too slight of build or youthful to so quickly lure Blanche into his good graces, and the nurse didn’t exude enough intimidating authority. Cullen Gandy as the collector and Blanche’s ex-husband was perfect.

Brad Dalton’s direction was specific, detailed and creative. The minimalistic set included chairs, a table and a bed, with the orchestra placed upstage behind the singers, dynamically conducted by the young Evan Rogister.

This production from Lyric Opera of Chicago was cost-effective and diverged from the initial production, which had a traditional set and premiered in 1998 at the San Francisco Opera.

The Stanley replicas who doubled as Stanley’s poker buddies began the action as the audience was being seated and during intermissions. There was no curtain. Only effective lighting brought us in and out of the action.

As for André Previn’s score, it seemed like a work in progress. I say that because I actually wanted to leave at the conclusion of Act 2 because I couldn’t weave the music with the characterizations to realize a work of art that was equal to or superior to the Williams play. The orchestration seemed like background music for the singers who were simply speaking on notes. Speech level singing came to mind, not really recitative, even though the performers were truly singing dialogue on notes, and sometimes the dialogue sounded mundane. Of course I wasn’t sitting with the play and libretto in front of me. But because I had put some of the dialogue to memory, I knew that the libretto followed the text of the play with some liberal variation.

The orchestral score seemed superior to the vocal score because at times, the two sopranos sounded like tweety birds due to the high tessitura which sometimes seemed stuck on one plane so that the vocal sound almost became annoying. I couldn’t even tell if the singers had quality voices even though I knew that they did. The composition just didn’t allow me to make the determination.

When Ryan McKinny was dramatic, his bass-baritone carried the drama. But Renée Fleming is a soprano known for her lyricism, and the high lyrical sound just didn’t work well with heightened hammered drama. It wasn’t her fault, though. She was wonderful.

Modern operas are always filled with atonal dissonance, and this opera is no exception. But the dissonance in “Streetcar” seems amazingly appropriate. It is blended well with a bluesy jazzy feel and music reminiscent of Richard Strauss, George Gershwin, Benjamin Britten, Alban Berg and Leonard Bernstein’s “Westside Story.” With strings, woodwinds and a brassy quality heavy on the trumpet and trombone, the orchestration sounds like 1940’s-era New Orleans mood music with voices imposed on top of it.

Renée Fleming

Before writing more about Miss Fleming, it was necessary for me to explain why the opera seems like a work in progress and doesn’t reach its potential until Act 3.

Fleming was marvelous throughout, but she was still singing like an opera singer performing for an audience — unable to touch us emotionally like an actor would until Act 3. This was due to the vocal score which fits her tessitura, not to her performance. Her glimmering voice was mesmerizing with some rich mezzo-like accents. But none of the music, not even the arias of the other characters, enabled the audience to stop, as in Mozart, and think: “Wow, that was glorious.”

For “Streetcar” to succeed as an opera, the music must enhance the telling of the story or should add something new to Williams’ text. If Williams’ words are better said by an actor in the play than sung, and if the music does not add anything unique to the opera genre, then the opera cannot work. That is why a poetic classic like “A Streetcar Named Desire” is difficult to adapt as an opera.

Finally in Act 3, the opera came into its own. During the first two acts, I was envisioning Vivien Leigh, Ann-Margret and Jessica Lange as Blanche — especially Jessica Lange who created a multi-dimensional character with emotional depth and artistry.

But then in Act 3, the rape scene was musically charged and emotionally riveting. Both Blanche and Stanley were alive and real. And finally, finally Miss Fleming sang “I Can Smell the Sea Air,” and the sound was gorgeous. Previn had given her a memorable aria that allowed the audience to hear the beauty of her resonant sound.

So to me, this opera is a work in progress because to make it equivalent to Williams’ poetic play, the opera version of “Streetcar” should include more lush melodic harmonies on the level of Blanche’s last aria, which is competitive with the music of the great opera composers of the past. Although we may not have seen Blanche’s true madness, we saw her drifting off into an ethereal world where she was no longer in touch with reality.

When the nurse kept repeating, “These fingernails have to be trimmed,” I died a thousand deaths. And as Fleming sang, “Whoever you are, I have always depended on the kindness of strangers. Whoever you are . . . whoever you are” — Fleming finally became Blanche DuBois and reached us. She was magnificent. And that is when I realized that Williams, Previn and the librettist had finally created an opera.

Director: Brad Dalton

Conductor: Evan Rogister

Lighting Designer: Duane Schuler

Costume Designer: Johann Stegmeir

Production: Lyric Opera of Chicago

Costumes: Provided by Washington National Opera

and Lyric Opera of Chicago

Critic’s Note: In deference to the composer and librettist, I need to write that my review is a review of the opera as it is, not as it could have been or could be. I realize that many factors contribute to a final composition. With a classic play like Tennessee Williams’ “A Streetcar Named Desire,” when the words are music to begin with, it is difficult to insert the dialogue into the mouths of singers over an orchestration so that the words have the same impact they do in the play. Music has time signatures, and the length a note is held has an influence on the language. So if the word “perspiration” works in the play, for example, the same word held in the context of an operatic phrase could accentuate it quite differently so that it simply sounds out-of-place in the context of the opera. Alas, some of the words in the libretto sounded mundane with far too much focus on them.

Even translating an opera from one language to another is a cumbersome job because words and syllables do not always match the notes that must be sung. So attempting to match Tennessee Williams’ words with a score was no doubt a daunting compositional task for the composer and librettist.

I have read that the Williams estate had a permissions agreement to adapt the play to opera so that the opera would maintain the integrity of the play’s story and much of the text, which was adhered to by the producing company, the composer and the librettist. The conditions imposed on them therefore limited their creativity.

The opera would have been quite different with a libretto that did not have to follow the play’s text. It might have been less wordy, and the accents on the words might have been more adaptable to the singers’ voices. The text would not have been compared to the poetic dialogue of the play. And a better marriage between the libretto and the vocal and orchestral scores might have ensued. Even the breathing of the singers must be considered to create vocal lines that tell the story.

So although I wrote that sometimes it is better to write new operas with plots that have never been told before so that the new operas will not be compared with the originals, it works to utilize an already existing story, but without attempting to create a carbon copy of the original by simply transferring the words to the different genre. If the original genre was successful, the opera genre should not have to compete. Each work should stand on its own.

Therefore, the opera “A Streetcar Named Desire” is what it is, and I have reviewed it as such. Had Previn and librettist Philip Littell started with a totally clean canvas except for the story, the result might have been quite different.

However I am sure that both the estate and the composer and librettist were attempting to develop a work of art that the playwright would have approved of. Writers do not like their words altered. However in the case of opera, the writer or representative of the original work should have a knowledge of music to draw the most optimal parameters for the work being developed. If an opera is to be successful, there must be flexibility from genre to genre.

But by the same token, if the librettist is left to create his own dialogue and the play is as poetic as “Streetcar” — it seems futile to even try. How could any other words compete with those of Williams in the context of the same story?

So in essence, with “Streetcar,” it is probably impossible to please all the parties, so maybe it was an implausible idea on the part of the estate and the opera’s creative team to authorize the project in the first place.

However, if I didn’t know and love the play; if I hadn’t have put some of the dialogue to memory — I would have been very accepting of this opera. The singers were terrific actors with a superb director. Renée Fleming outdid herself vocally and physically, and even though she created a devastatingly tragic character, she seemed to love being on the stage throwing her all into the role just for us. She gave us a wonderful night at the theater to remember. So what could be wrong with that?

Posted in Commentary/Opinion, Opera Reviews, Reviews, Theater Reviews