Sometimes, as with last week’s upending election, history seems to jump to an entirely different, unimagined timeline. The individuals who cause these disruptive changes have been a fascination for Philip Glass, whose first three operas form the so-called “Portrait Trilogy” about visionaries who transformed their respective eras.

Sometimes, as with last week’s upending election, history seems to jump to an entirely different, unimagined timeline. The individuals who cause these disruptive changes have been a fascination for Philip Glass, whose first three operas form the so-called “Portrait Trilogy” about visionaries who transformed their respective eras.

Akhnaten, seen at the Los Angeles Opera on November 13 tells the story of the Egyptian Pharaoh Akhenaten (Amenhotep IV) who abandoned traditional Egyptian polytheism to worship only the deity Aten. While this is regarded as an early outbreak of monotheism, technically it is better described as monolatry since he did not deny the existence of the other Gods, but chose not to worship them. Glass’s other two works in the trilogy are Satyagraha with its all too timely lessons on civil disobedience and Einstein on the Beach, whose significance for the current day, I’d rather not contemplate.

This piece, with the its musical language of slowly evolving phrases is a reinvented Baroque opera in its form: Accompanied narrations serve as recitatives, allowing the ensuing numbers to contemplate the implications of the action described. This structure creates formidable challenges for directors who must manage with long stretches of music that have no required or implied action.

Director Phelim McDermott, who co-directed Metropolitan Opera / ENO production of Satyagraha with designer Julian Crouch, here has the sole directorial credit. His production displays many of the virtues of that landmark staging: the poetic realization of the themes and dramatic situations of the opera, the metamorphosis of everyday materials into powerful, beautiful images and the masterful handling of massed movements by the chorus.

Akhnaten’s reign is presented as a sublime, if transient, triumph over Chaos – the unwieldy multiplicity of divinities; the disloyal cliques of priests and military leaders, the fragile union of Upper and Lower Egypt. Akhnaten’s efforts to conquer disorder are manifested as juggling – a simple if improbable source of stage pictures of great variety and power.

After the prelude, the show opens with the elevated chorus members each juggling a single ball in unison while a troupe of jugglers work through much more intricate routines below. It’s mesmerizingly hypnotic. These hyperkinetic sections are in stark contrast to the moments of Akhnaten’s supreme triumph.

For Akhnaten’s great love duet with Nefertiti and the hymn that ends the second act, time nearly does stand still as the characters move slowly against a shifting, luminous backdrop. It’s superficially recalls Robert Wilson, but the effect here is romantic and has none of the clinical coldness of Wilson’s work.

For Akhnaten’s great love duet with Nefertiti and the hymn that ends the second act, time nearly does stand still as the characters move slowly against a shifting, luminous backdrop. It’s superficially recalls Robert Wilson, but the effect here is romantic and has none of the clinical coldness of Wilson’s work.

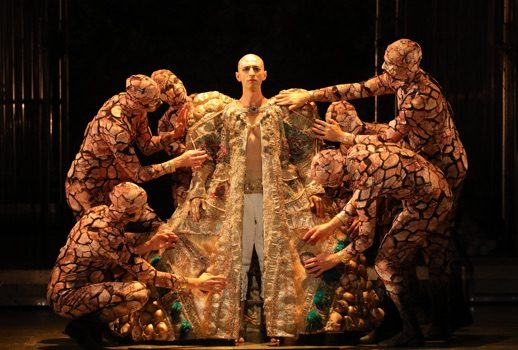

Anthony Roth Costanzo’s performance in the title role will certainly become an interpretation that will be spoken about in hushed awe for some time to come, and not just because he performs naked for a considerable portion of the first act as he is anointed and slowly clothed for his coronation. At the intermission, the woman behind me explained helpfully to her companion, that he had to perform naked so that we would know it was a man singing!

His performance was remarkable for his focus and intensity, vocal and physical dexterity, and delicate shading he brought to the music. He was particularly well matched by J’Nai Bridges as his wife Nefertiti who brought a similar delicacy and grace to her music. Their Act II duet achieved an ecstatic sublimity.

Amongst the uniformly strong cast, it is also worth singling out the contribution of Zachary James as The Scribe, the non-singing narrator. He supplied the necessary authority and passion and scaled unexpected dramatic heights in the peroration after Akhnaten’s death, delivered with ferocious tenderness as he carried dead pharaoh across the stage.

The chorus, prepared by Chorus Director Grant Gershon, handled their challenging music and intricate staging with noteworthy ease; The slow motion riot as they besieged Akhnaten’s home before his death, is an effect that so many have tried; here, it finally worked. Unfortunately, the orchestra under composer Matthew Aucoin fared considerably less well.

The strings lacked weight and balance; they had tuning problems through the evening. At times, the orchestra seemed to lose its focus and the ensemble suffered, most notably when the percussion drifted off from the rest of the orchestra in a crucial moment in the third act.

The strings lacked weight and balance; they had tuning problems through the evening. At times, the orchestra seemed to lose its focus and the ensemble suffered, most notably when the percussion drifted off from the rest of the orchestra in a crucial moment in the third act.

Sets were by Tom Pye. He delivered a complex, industrial, multi-level structure that was reconfigured in surprising ways over the course of the evening, even sliding magically to the sides for the end of Act II so that Akhnaten can rise against a stage filling representation of Aten, the disk of the sun. The costumes by Kevin Pollard were Egyptian in their inspiration, but drew upon the imagery of many cultures for their execution.

Akhnaten had a dazzling series of elaborate looks that evoked the androgynous depictions of Akhnaten in the artwork from his time. (I think Akhnaten had more costume changes than Massenet’s Manon.) Bruno Poet provided the expressive lighting. Sean Gandini was credited in the program as the Juggling Choreographer(!) He devised a series of inventive, apt movements capturing everything from the building of the holy city of Akhetaten, to the collapse of Akhnaten’s empire and his death

If one of La Cieca’s recent blind items is to be interpreted correctly, this show is headed to New York City soon. I can’t wait to see it again.

Photos: Craig T. Matthew/Los Angeles Opera

Comments