People who claim that opera is nothing more than a glorified pantomime would have their prejudices confirmed at Deutsche Oper Berlin's Un ballo in maschera. This is, however, high praise. It’s an evening of camp entertainment, not a philosophy lesson. The story is a slim one, and as with many Italian operas can be summed up in less time than it takes for the overture to play out. The most surprising thing about this opera is that the ending doesn’t hinge on mistaken identity at the masked ball, as the title would massively hint. But then Verdi had already served up that plot twist in Rigoletto seven years previously.

Forbidden love and royal assassination – that’s what it all boils down to. It is based on a true story, although Verdi spent so many years in court trying to get the censors to stop messing with him that most of the facts have been tweaked out of existence. As opposed to the real-life King Gustav III taking thirteen days to die from his injuries (post-spoiler alert), here the monarch gives up the ghost almost instantaneously, thereby dramatically truncating the opera to a mere three hours. Another shocker is the fact that the King is actually innocent of the crime (of seducing his best friend’s wife by the gallows). Of course, if he had actually mentioned his innocence at any previous point he wouldn’t be dead, but this isn’t ‘verismo’ opera.

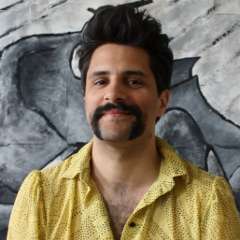

Tenor Yosep Kang, singing the role of King Gustavo, absolutely stole the show. Every note seemed to energize him into further feats of derring-do. He has a very Italian way of singing, seemingly effortless, rich and strident. For many people the splendour of the human voice is the hook upon which the hat of opera hangs, and if that is true for you it would be hard to better this experiene. Roman Burdenko’s portrayal of Renato was not a stand-out performance, but among such a stellar cast this is not a terrible position to be in. He served the story and the character well.

Tamara Wilson singing the triangulated lover Amelai has a beautiful voice, with uncommon flexibility, wringing drama from every line. She floated with delicacy when required, or burst into vocal flames at the sizzling crux of the drama. A pure treat came in the form of Heidi Stober as Oscar the Page. She has a consistently wonderful way about her, always shaping the music intelligently and in keeping with the character.

One of the other vocal joys of this opera comes with the low, low depths of mezzo Ronitta Miller. Verdi’s gloomy sorceress is not made of flighty wisps, but is rather rooted in earth. Her voice is therefore required to be mesmerically deep, and Miller delivered bewitching results.

Ido Arad conducted like a boss, in place of his actual boss, Donald Runnicles. The opening is one of Verdi’s most contrapuntal, and Arad made every line ring with clarity. Particularly fantastic was the decision to take ages rearranging the set between scenes and therefore grab the audience by surprise when the music slammed back into full force just before the curtain went up. Genuine frisson!

Director Götz Friedrich (with his pair of set designers) created an atmospherically inconsistent spectacle. From the fabulously eerie lair of the sorceress, to the curiously plain white domestic setting of Renato and Amelia’s home, and finally the (presumably symbolic) miniature ballroom that the King plays with. Each was perfectly serviceable in its own way, but there wasn’t much overall coherence or grand vision in evidence.

Opera-goers have been spoiled over the years with irrelevant and gratuitous orgies (onstage). This production made me realise just how well that stuff had been choreographed in previous settings, because here in place of sauce and lasciviousness was sand and frigidity. That was also true of the dancing in the ball scene. Fairly key, you might think, but with each group of dancers moving at a different speed (though not a bad idea on paper) the lack of cohesion turned out to be one of the few inconsistencies of the production.