by Steve Cohen

The

next time I attend Wagner's Ring, I'd like to see Siegfried and

Götterdämmerung on the same day. Better yet, I'd like to see

them back-to-back, Siegfried in the afternoon and Götterdämmerung

the same evening with minimal pause.

The

next time I attend Wagner's Ring, I'd like to see Siegfried and

Götterdämmerung on the same day. Better yet, I'd like to see

them back-to-back, Siegfried in the afternoon and Götterdämmerung

the same evening with minimal pause.

Admittedly, this is an unrealistic dream. But fueling my desire is the fact that Götterdämmerung 's opening scene has greatest impact when you see it in close contrast to the preceding opera's happy finale.

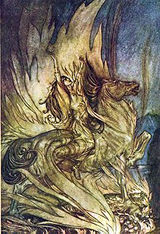

Götterdämmerung, The Twilight of the Gods, begins with three women talking about the past and, when they turn to speak of the future, everything breaks off. These are the Norns who supposedly know everything about past and future. They are weaving the long rope of destiny and then, abruptly, it snaps. The scene goes dark and we are plunged into despair that the end of their world is imminent.

I am reminded of a bit of Shakespeare's three witches who open Macbeth by somberly contemplating the future.

The Norns' scene gives us some helpful background to the story we've been watching for more than ten hours. They sing about how Wotan, early in his career, cut a branch off the World Ash Tree, source of all wisdom, and made from it his spear, and he drank from a spring of knowledge near the tree's roots. He gave something precious in payment for this wisdom - one of his eyes, which is why he wears a patch. Through three operas we have seen it and only now do we learn its significance.

The Norns also tell us that the ash tree has died and Wotan is cutting its branches into firewood and stacking them. He is resigned to the death of the gods and intends to burn his palace to the ground.

Now the story returns to the narrative of Siegfried and Brünnhilde. By and large I avoid compositional details such as key and meter because many readers find it too technical. But here it is an essential part of the drama. Music for the older Siegfried has become more adult, in solid two-four time rather than the youthful six-eight of the previous opera, and a minor harmony indicates coming sorrow. The theme of the mature Brünnhilde is beautiful and appropriately clinging. She sends him off to new adventures, asking him to keep their love in mind as the orchestra gives us wonderful traveling music, the "Rhine Journey." This opera was composed after Wagner took a 17-year break from the Ring and he had written Tristan und Isolde and Die Meistersinger in the interval. Not surprisingly, his orchestral music is even more complex and symphonic than before.

Siegfried discovers a population of Gibichungs living near the Rhine. We have received no preparation for their entrance; we know little about the Gibichungs and have scant reason to care except that Siegfried's interaction with them is going to lead to his death. Siegfried meets Gunther, the king of the Gibichungs, and his half-brother, Hagen, who was fathered by the villain of the Ring, Alberich.

Why doesn't Siegfried just say hello and goodbye to these guys then go on his way? Why is Siegfried so eager to bond with them? Why does he want to be their "blood-brother"? I can only find an answer by imagining that Siegfried, who is Wotan's grandson, feels connected because he intuits that Alberich and Wotan are two sides of one being, mirror images to each other.

Wotan refers to this in Siegfried when he says he is Licht Alberich, "Light Aberich" who gains power by contracts, in contrast to Schwarz Alberich, "Dark Alberich," who attains power through force. Alberich does not accept being labeled as the sole villain and he says to Wotan: "You have caused distress to the world through your guile...you treacherous trickster." Each has enabled the other. Alberich's theft of the gold from the Rhine gave Wotan the means to pay for the construction of Valhalla.

Both of them were dissatisfied with the world, witness Wotan's need to construct a Valhalla. When my wife and I visited King Ludwig's castle, Neuschwanstein, we saw it as that monarch's Valhalla. Ludwig, you will recall, adored Wagner's music and the ornate castle contains murals and sculpture of Wagnerian opera scenes. (Pre-Ring, of course. Ludwig was declared insane and died before Wagner completed the cycle.)

Getting back to Act One of Götterdämmerung, Siegfried accepts a drink which makes him forget about Brünnhilde. He falls in love with Gunther's sister, Gutrune, and, when he is told that Gutrune can not marry until after her brother has, Siegfried promises to help Gunther win Brünnhilde for his bride. This is in contrast to the match-making that we see in Tristan where a magic potion seems to cause Tristan and Isolde to fall in love with each other, but there was palpable chemistry before they shared a drink so we are not forced to believe that magic alone propels the plot.

W. S. Gilbert, around the same time, wrote a libretto about a magic lozenge that would change the plot of a G&S operetta. Arthur Sullivan, his partner, rejected the idea as artificial and lacking in "human interest and probability." Gilbert's persistence in pushing this device contributed to the break-up of that theatrical team.

Now comes a quiet scene of drama. Brünnhilde, alone on a rocky plateau, is visited by her Valkyrie sister Waltraute. Brunnhilde hopes that her sister has come with news that her father, Wotan, has forgiven her for defying him. Not so. "Listen carefully," says Waltraute, as she tells that the curse is affecting Wotan to the point where he now sits silently with the other gods in their castle awaiting the end of the world. The controlling figure of the early parts of the Ring now is an aging, disillusioned pessimist. This mirrors Wagner himself, who conceived the opera as a revolutionary 35-year-old and finished composing it at age 61.

Waltraute begs Brünnhilde to return the ring to the Rhinemaidens to lift the curse. But Brünnhilde refuses to relinquish Siegfried's token of love and Waltraute rides away in despair. The duet contrasts Waltraute's dark mezzo with Brünnhilde's higher voice.

Siegfried arrives, disguised as Gunther, and claims Brünnhilde as wife. Brünnhilde resists but Siegfried overpowers her, snatching the ring from her hand and placing it on his own at the end of Act One.

Act Two contains the only use of chorus in the entire Ring. The vassals of King Gunther sing: "Waffen! Waffen! Waffen durchs Land! Gute Waffen! Starke Waffen! Scharf zum Streit." ("Weapons! weapons! Take up your weapons! good weapons! strong weapons! sharpened for battle.")

When the chorus sings: "Waffen," the name of Hitler's elite corps, it makes us uncomfortable. We must realize that Wagner did not invent nor know of the Nazis although some of his writings inspired them.

In this act Brünnhilde discovers that Siegfried has been unfaithful to her and she's furious that "he forced me" to submit. Brünnhilde and the Gibichung brothers agree that the punishment for Siegfried must be his death, and the revengeful Brünnhilde reveals to Hagen the hero's one vulnerable spot, which is his back. My partner says this sounds like is bad television drama, and I regret that it was a potion that drove Siegfried to his doom rather than something in his character or willful action on his part. This is the weakest moment in the drama of the Ring.

The last act shows us the Rhinemaidens still bewailing their loss, and Siegfried ignores them. Hagen stabs Siegfried to death and his body is borne away to magnificent funeral music. Back at the hall of the Gibichungs, Hagen admits his trickery and kills his own brother. Brünnhilde orders a funeral pyre for Siegfried, places the ring on her finger and rushes into the flames. She sings that Siegfried was innocent and "everything is now clear to me... The fire that consumes me shall cleanse the ring from the curse. You in the water, wash it away." She, like Isolde, wants to be one with her beloved in the intensity of love.

As the river overflows its banks and the Gibichung hall is consumed, Hagen sees the gold in the possession of the maidens and plunges into the water to chase them. They encircle him with their arms and draw him down to his death. Valhalla is seen in the distance, in flames.

The orchestra reprises some of the best music from the cycle, reminding us of the Magic Fire, the Ride of the Valkyries, Siegfried, Twilight, Redemption, Brünnhilde's love and Valhalla. Wagner pumps up the pomp associated with the Valhalla music into a blazing grandiosity, indicating the hollow glory of Wotan's ambitions. Then the music of the Rhinemaidens returns, bringing us full circle to where the Ring began.

But not quite. The orchestra plays a full, D-flat major chord, a step below the E-flat of the Rheingold prelude, suggesting Nietzsche's idea that patterns will recur but we never arrive back at precisely the same place.

These gods have been destroyed, and suppositions abound about what this signifies. The death of religion? The triumph of science, or of nature? Dämmerung could also mean dawn, since the term is used for both the rising and setting of the sun. Wagner's stage direction is: "Among the ruins of the collapsed hall, men and women stand spellbound, looking up at the growing light in the sky."