A whisper of vaudeville, a burst of cimbalom, shrieks, whistles, bells and the brief wheeze of accordions, each sound exquisitely sculpted, pierces the silence. György Kurtág’s long-awaited first opera was never likely to sound like anything else that comes under that title. Nor does it. Aged 92, after decades of resistance to the form, despite the cajoling of professional friends, the Hungarian composer has had his Fin de partie premiered at La Scala, Milan.

The opera’s full title is Fin de partie: scènes et monologues, opéra en un acte. While Samuel Beckett’s play, written in French and later translated as Endgame, runs straight through uninterrupted, Kurtág’s work consists of short scenes. The curtain comes down frequently, which doesn’t break the continuity because, in a sense, there is none. Kurtág’s compositions have always been jewelled miniatures. Fin de partie is like a glistening string of them, perfectly suited to the granular nature of Beckett’s text. Only now has Kurtág agreed to release this work in progress (he has set roughly 60% of the text), after postponements at Zurich, Salzburg and, three years ago, Milan.

It feels complete. At over two hours without interval, it’s already a challenging evening: apart from a scurry of exits early on, it held its international audience (which included the prime minister of Hungary, Viktor Orbán) captive. Only the composer was absent, unable to travel from Budapest where he lives in an apartment at the top of the city’s Music Centre. (If London’s Centre for Music is ever built, someone might bear this in mind for the UK’s senior composers.)

Reviewing the world premiere of Beckett’s play at London’s Royal Court, Kenneth Tynan triumphantly scorned it as too bleak, “stamping on the face of mankind” (the Observer, 7 April 1957), likening its characters to Francis Bacon’s newly displayed “screaming popes”. Kurtág saw it in Paris the same year. For the young composer, instead, it was a lasting revelation. He had just arrived in France after the 1956 Hungarian uprising: “I understood hardly anything when I saw the play. But then I bought the two [Beckett] texts, Endgame and Godot, and they became my bible. Truly.”

This context is vital. Kurtág, the last survivor of the group of influential European avant garde composers born in the 1920s – Boulez, Ligeti, Xenakis, Berio among them – has been steeped in Beckett all his artistic life. His pianist wife, Marta – they married in 1947; their lives are intertwined; she sits beside him, commenting, advising, as he works – spoke recently of the opera being the couple’s own endgame.

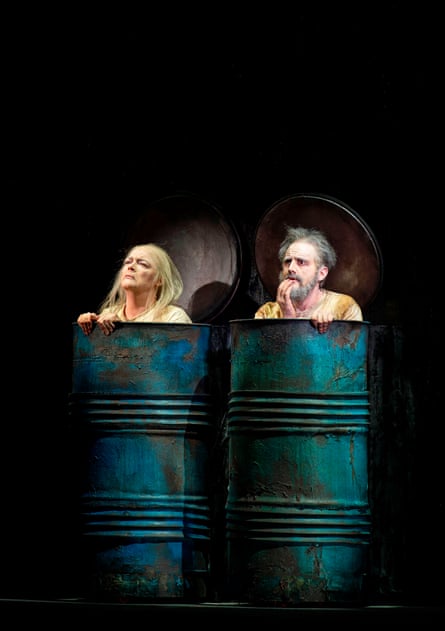

There’s scarcely a plot. Four people, variously immobile, are confined to a disintegrating existence. Hamm, blind and chairbound, superbly, inexhaustibly sung by the Norwegian bass-baritone Frode Olsen, is the “king”. He bullies, but relies on his “knight”, Clov, who cannot sit down – performed with ferocious cogency, each heaving step an effort, by the British baritone Leigh Melrose. Hamm’s parents, Nell (British contralto Hilary Summers touchingly, absurdly romantic) and Nagg (Italian tenor Leonardo Cortellazzi, edgy, strident), have lost their legs. They live in rubbish bins, mostly with the lids down. Nell dies. Hamm is abandoned, withdrawing from the world under a bloodied handkerchief.

The music, expertly and diligently conducted by Markus Stenz, traces the text in conversational sympathy, with stop-start blurts and urgent, delicate fluencies. The 60-strong orchestra, in addition to the usual lineup, is dominated by low instruments and tuned percussion: alto and bass flute, cor anglais, contrabassoon, tuba; celesta, pianino (with supersordino – permanently muted), piano, as well as cimbalom. Pierre Audi’s production, designed by Christof Hetzer, with chilling use of shadow play by lighting designer Urs Schönebaum, is stark, unyielding, economic. A shack of a house, which revolves for each scene, stands alone in blackness. Beckett once told an actor preparing the play that he must “fill my silences with sounds”. Kurtág has done just that. Far from stamping on the face of mankind, this masterly composer has caressed it with all his own life’s worth.

Alexander Pereira, artistic director of La Scala, the man who wouldn’t say no to Kurtág and chased him round the opera houses of Europe to secure this world premiere, said afterwards that it was as important and thrilling as hearing a new Britten opera. As the curtain rose at English National Opera’s War Requiem, I had his words in mind. Britten’s work isn’t an opera but has been given a full staging, in an opera house, by ENO, directed by Daniel Kramer, with designs by the Turner prize-winning photographer Wolfgang Tillmans.

Images of the dead or maimed, of nature destroyed, of the bombed shell of Coventry Cathedral (so closely associated with the 1962 premiere of this work) provide backdrops for contemplation. The chorus, much of the time, move as one, bodies strewn, bringing to mind the strange symmetries of CRW Nevinson’s war art. All culminates in a sensuous, green redemption, depicted by a huge tree in full leaf.

Whether you get on with the production will depend in part on your enthusiasm for grand choral works being staged. If it brings the music to a wider audience, all to the good. A literalness takes over – how can it not – which for some will underline, for others undermine, perception of the original. Many in the audience were visibly moved. I struggled to match what I heard and what I saw and was left somewhat unengaged.

ENO had an outstanding lineup of soloists – Emma Bell, David Butt Philip and Roderick Williams – with top-class singing from the company’s chorus, joined by ensemble singers from the recent Porgy and Bess, as well as Finchley Children’s Music Group choir. To sing or play in this work is an experience you never forget. Even if some of the spatial elements were lost, Martyn Brabbins, ENO’s music director, and the orchestra, brought out the music’s torment and grief.

Star ratings (out of 5)

Fin de partie ★★★★★

War Requiem ★★★

Fin de partie will be at the Dutch National Opera in Amsterdam next year, 6, 8 & 10 March 2019

War Requiem is in rep at the Coliseum, London, until 7 December

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion