Can You Make Don Giovanni Feel Relevant? HGO Just Did.

The cast of Houston Grand Opera’s Don Giovanni.

Image: Lynn Lane

Don Giovanni is problematic—no one denies that. But the opera was smarter than its time, and in its newest reimagining under director Kasper Holten, HGO presents a version of Mozart’s masterpiece that’s darker and disturbingly relevant. The Don is portrayed as what he is: not an amoral, badass cultural hero with an insatiable zest for life and ladies, but the powerful, violent, self-entitled narcissist in Lorenzo Da Ponte’s libretto, who serially preys on women and thinks he is doing them a service. The music is still glorious, but underneath it, HGO’s Don Giovanni is not merely a titillating comedy or a moralizing story; it’s complex and uncomfortable, as it should be.

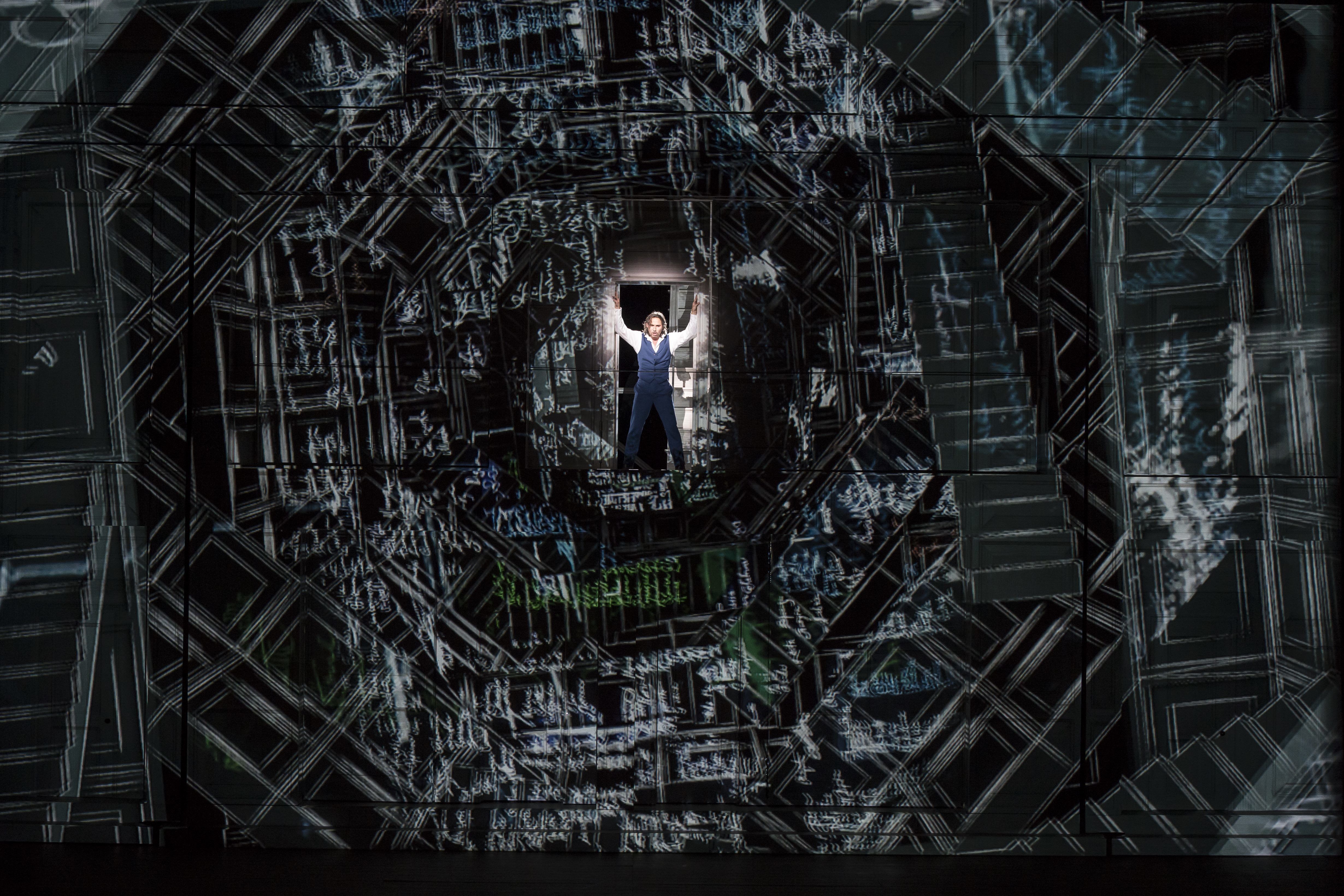

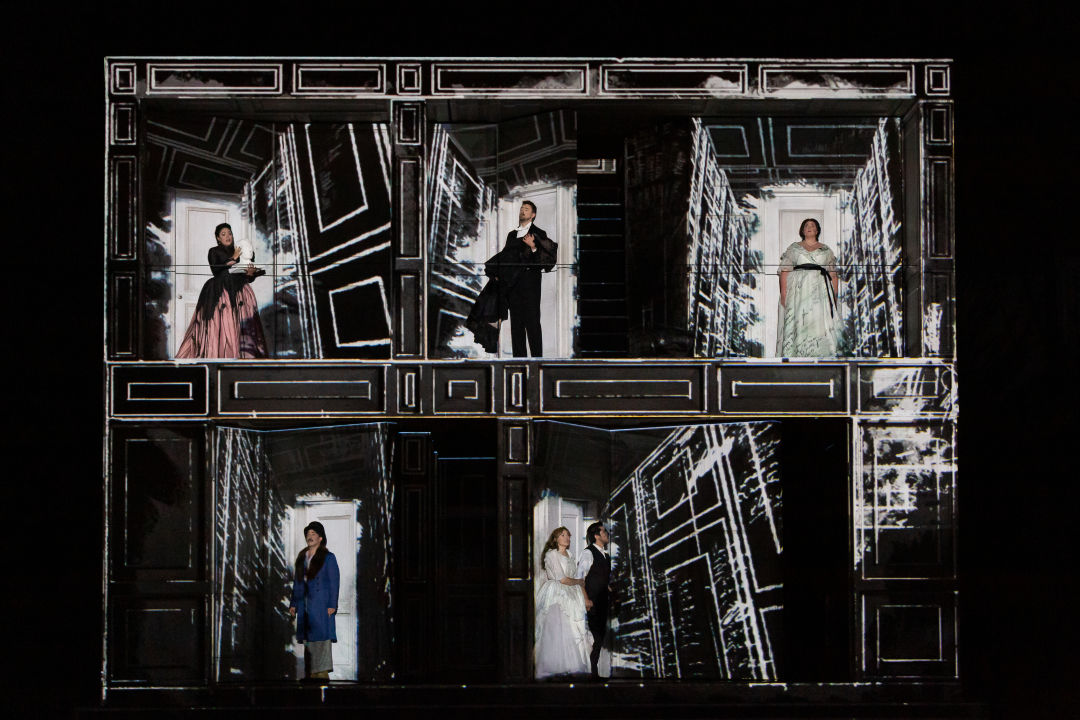

At the heart of Holten’s production is a set designed by Es Devlin, a two-storied revolving cube that opens and closes like a dollhouse, with improbable staircases and disappearing corners like in an Escher drawing. The audience’s perspective constantly changes, and sometimes the set rotates even in the middle of arias, giving the audience a glimpse of what Don Giovanni is up to in another room. It’s like his presence is still felt when he is not there.

The set also serves as a blank slate for the video projection, designed by Luke Halls. During the overture, the names of the Don Giovanni’s woman “conquests” appear in a video projection all across the stage, white letters scrawled all over the windows and door panels (they appear later in the fabric of Elvira’s dress, designed by costume designer Anja Vang Kragh). The escalation of those 2,065 names is funny at first, but after a while it becomes a little sickening. In some ways this production undermines its own humor—there are moments of comic relief, like when the Don’s servant Leporello tries unsuccessfully to woo (and grope) women—and we laugh, but the laughter always feels uneasy.

Ryan McKinny and Ailyn Pérez.

Image: Lynn Lane

Bass-baritone Ryan McKinny makes his role debut as the title character, and he’s magnetic. We first see Don Giovanni as he’s running out of the bedroom behind Donna Anna, shirt unbuttoned and hair disheveled, and he’s tall, lithe, and dangerously charismatic. When he flashes his rakish smile, it’s lethal, and it certainly doesn’t take much imagination to see why all those women (2,065 in total) couldn’t resist him. At moments, we almost begin to root for him; it’s where the disturbing ambiguity of this opera lies, that his allure and his privilege allows him to do whatever he wants to do. One of the most gorgeous musical moments is his aria to Elvira’s maid, “Deh vieni alla finestr.” McKinny cuts a languid figure, lying beneath her window disguised as his servant Leporello, and his serenade is so meltingly beautiful, so luminous, that we forget how insincere the whole thing really is.

The rest of the cast is stellar. As Leporello, Giovanni’s rumpled, clownish servant, baritone Paolo Bordogna steals every scene he’s in, possessing a delightful knack for physical comedy and an equally impressive voice. Melody Moore cuts an imposing figure as Donna Elvira, the Don’s abandoned lover, and she navigates the character’s swirling emotions with convincing ardor. But even as she warns the other women about Don Giovanni she continues to pine for him herself, and we can’t decide if she’s an example of tragic dignity or tragic stupidity. Ailyn Pérez projects passion as Donna Anna—especially in her empowering aria “Or sai chi l’onore”—and her magnetic stage presence is fiery, almost on the same level of the Don. Her lovable but stuffy fiancé Don Ottavio (played by magnificent tenor Ben Bliss) and the peasant Masetto (bass-baritone Daniel Noyola) are sincere but ultimately ineffective against the Don. Dorothy Gal plays naive peasant girl Zerlina, and her voice, though lithe and exquisite in tone, noticeably lacked in projection.

Unfortunately many of the subtleties from the pit were lost on the audience due to the visual overload. I often found myself so engrossed by the never-ending special effects—at one point the entire projection began spinning around, a staircase vortex straight out of Hitchcock’s psychological thrillers—that the sublime music faded into a mere backdrop. And it’s a shame, because the orchestra, conducted by Cristian Macelaru, brought to life Mozart’s masterpiece with incisive accuracy and nuance (the harpsichord continuo in recitatives and gentle mandolin strums in Don Giovanni’s serenade were spot-on).

But the projected images make this production work. The red wash of blood when the Don murders Anna’s father could have been more subtle, but when he descends into insanity towards the end, the names of the women he’s bagged start dripping in bleeding colors, staining and mottling the walls, reminiscent of Rorschach blots. He’s sinking under the weight of all that ink. And the ghostly female figures that haunt his space aren’t written in the opera, but they are real people, and they stand unobtrusive and silent in open doorways and dark corners, their presence keenly felt. They reappear at the end, flanking the Commendatore (bass-baritone Kristinn Sigmundsson) as he arrives and offers the Don one last chance to repent. Don Giovanni adamantly refuses, and he’s left alone, in darkness—his worst kind of hell. At least in this retelling, the voices that speak loudest are the voices of the women.

Thru May 5. Tickets from $25. Wortham Theater Center, 501 Texas Ave. 713-228-6737. More info and tickets at houstongrandopera.org.