United States Verdi, Il trovatore: Soloists, Chorus and Orchestra of LA Opera / James Conlon (conductor), Dorothy Chandler Pavilion, Los Angeles, 18.09.2021. (JRo)

United States Verdi, Il trovatore: Soloists, Chorus and Orchestra of LA Opera / James Conlon (conductor), Dorothy Chandler Pavilion, Los Angeles, 18.09.2021. (JRo)

Production:

Director – Francisco Negrin

Sets & Costumes – Louis Désiré

Lighting – Bruno Poet

Chorus director – Grant Gershon

Fight director – Andrew Kenneth Moss

Cast:

Leonora – Guanqun Yu

Azucena – Raehann Bryce-Davis

Manrico – Limmie Pulliam

Count di Luna – Vladimir Stoyanov

Ferrando – Morris Robinson

Ruiz – Anthony Ciaramitaro

Ines – Tiffany Townsend

Messenger – Orson Van Gay II

In spite of the despairing drama on stage, gratitude and joy reigned as performers, audience and staff of the LA Opera joined together to cheer the return of a full schedule of live performances at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion. The joy didn’t stop there. James Conlon, one of the foremost Verdi interpreters, conducted the LAO Orchestra in a balanced and dynamic rendering of the composer’s middle-period masterpiece and eternal crowd-pleaser. With its perfectly calibrated sound, the orchestra allowed the gifted singers on stage to bloom.

Musically, the night was a raging success. Debuting in the role of Manrico, Limmie Pulliam’s silky tenor was exquisite in the pianissimo passages and resonant in the character’s impassioned arias. Guanqun Yu as Leonora sang with poetic grace, and was mesmerizing in the intimacy and beauty she brought to her expressive Act IV solo.

Mezzo-soprano Raehann Bryce-Davis sang the pivotal character of Azucena. Her tone was warm and lustrous, her vocal range considerable and her acting fearless in laying bare Azucena’s tortured soul. As Count di Luna, Vladimir Stoyanov, with his assured baritone, sang with pathos of his unrequited love for Leonora, while vividly performing what the role most demands – the brutality of an entitled aristocrat.

Morris Robinson’s Ferrando was stellar. His luminous bass never fails to spark wonder, whether singing Mozart or Verdi, Bellini or Glass. Also of note, Tiffany Townsend was a sympathetic Inez.

As for the libretto of Il trovatore, it is notoriously bewildering. If one of the first rules of drama is ‘show, don’t tell’, then Salvadore Cammarano’s libretto breaks that rule. Half the opera is back-story – the burning of Azucena’s mother, the stealing of an infant, the burning of Azucena’s biological child, the meeting and falling in love of Manrico and Leonora, and more. So much, in fact, that a hasty reading of a program synopsis cannot convey enough meaning to anyone new to the opera. In light of that, a satisfying production needs to clarify, rather than obscure, the meaning.

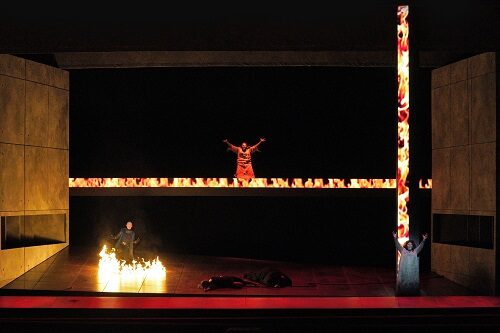

Barcelona-based director Francisco Negrin gave it his best effort, approaching the staging from Azucena’s perspective: through the eyes of a woman who today would be diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder. The idea was sound, the execution perplexing. The male chorus, with faces painted Dracula white and eyes blackened, was a nod to Azucena’s nightmarish perceptions. They hovered menacingly throughout the four acts, whether playing Romani people or soldiers, and it was difficult to differentiate between the two. Symbols abounded: a constantly burning flame, a meandering dead child, a scythe-bearing figure, a pillar pushed back and forth and, finally, Leonora dragging a dead body after she poisons herself. None of the symbols added to one’s understanding.

Due to COVID-related delays, the sets were stalled somewhere in the Pacific en route from Monaco. The LAO stage crew and scenic artists worked 14-hour days to complete new set pieces and to create pyrotechnic elements and lighting structures – a valiant effort, but the handsome, unvarying Minimalist set needed better illumination and more variety to match the passion of Verdi’s melodrama. Though the scale tended to dwarf the singers, the design proved particularly striking when Azucena’s dead mother appeared on an upper level at the back of the stage. Unfortunately, the severely raked floor made it difficult for the singers to maneuver naturally and impaired the acting, particularly in the scenes between Leonora and Manrico.

Nevertheless, the music prevailed, and the audience was rightly exuberant. Morris Robinson summed it up best. When taking his curtain call, he pumped his fist high into the air with joyful abandon, demonstrating what everyone thought and felt – LAO is back!

Jane Rosenberg