Royal Opera House 2021-22 Review: Peter Grimes

Allan Clayton Shines in Deborah Warner’s Unsparing Production

By Benjamin Poore(Credit: ROH 2022 (c) Yasuko Kageyam)

Benjamin Britten’s “Peter Grimes,” an opera of community disaster, has lately belonged in London to Edward Gardner in the pit and Stuart Skelton in the title role, both searingly brilliant. Deborah Warner’s new production, headed by tenor Allan Clayton, offers a vivid and contemporary alternative vision of the work that deserves to run and run.

In terms of setting, Michael Levine’s designs and Luis F. Carvalho’s costumes suggest the impoverished contemporary seaside towns of the southeast of England – Brexit-voting heartlands that have been rundown and failed by politics for generations, and whose anger is turned wildly in all kinds of reactionary directions. Not least towards Ellen Orford, who is set upon by the chorus in Act two after showing some sympathy for the outsider Grimes.

A Grimy. Hopeless World

It is a grimy, hopeless world, where exploitation, drug use – Ned Keene becomes a petty criminal wide boy – and poverty are grist to the mill of retributive violence. Sets are open and abyssal – they evoke the bleak landscape of Aldeburgh, but also the alienated landscape of the inner life in the piece. The overall effect is to depict a society that is damaged and damages, but this is not a production that sneers or dehumanizes. Cruz Fitz’s portrayal of the boy is nervy and fragile, every gesture convincing, and he works beautifully with both Clayton’s Grimes and Maria Bengtsson’s Ellen.

The complexity and emotional integrity of the production comes from superbly detailed directing, at the level of both named characters and, perhaps most of all, chorus. The latter move with an incredible feeling of threat and tidal grandeur in the great Act two and Act three sequences; but individuals within the crowd have clearly defined shapes and journeys across the stage – this is no undifferentiated mass, but rather a layered social structure with antagonism and nuances.

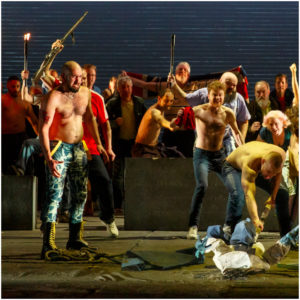

The social realism achieved through the detailing is remarkable: the Reverend goes litter-picking while the neofascist thugs party on, as other distinct groups come and go. In the Act one finale, an awkward disco dance accompanies ‘Old Joe has gone fishing’, which, as it goes on, progresses from being a well-observed piece of pub life to poundingly menacing. The Act three climax, lynching an effigy of Grimes, was brutally physical, the bare-chested dancers panting like animals into the great cavernous silences between chorus entries – an image from the production that deserves to endure.

To the realism Warner adds phantasmagorical, abstract elements: the first scene is not a courtroom but a dream, with Grimes reliving the incident with his former apprentice, set upon by flashlight wielding villagers and a sadistic Swallow, whose performance from Tomlinson reminds of his turn as the Doctor in Keith Warner’s “Wozzeck.” A boat hangs suspended in mid-air, with the gnawing threat that everything is about to come crashing down.

A final element in the mix is the aerialist Jamie Higgins, who, dressed as a fisherman, is alternately falling, soaring, and drowning, and whose movements coincide devastatingly with the score in the very final bars. It is a beautiful way of speaking to the fatal suspensions of Britten’s score. He is a both cipher for Grimes himself – a premonition of his suicide – but also a vision born from his guilt.

A Career-Defining Turn

Allan Clayton was first contacted by Warner about singing Grimes after his performance in Brett Dean’s “Hamlet” at Glyndebourne; last year he appeared at the ROH in HK Gruber’s music-theater romp “Frankenstein!!” His realization of Grimes as a character clearly draws on the psychological heft of the former and the vocal imagination of the latter. It should be regarded as a career-defining role, one of the most intense fusions of music and character to hit the Covent Garden stage in years. Clayton has built a powerful and humane picture of an individual who goes beyond categories like good and bad: traumatized, haunted, visionary, quick-tempered, but – most tragically – still capable of tenderness, even love, though he cannot realize them.

Vocally he is peerless, and has synthesized the work of his many peers in this role to create something distinctive. “Now the Great Bear and Pleiades” began with the creamy piquancy of Peter Pears’ head voice, before rounding and blooming into the lyric chest of Jon Vickers. The climactic duet with Balstrode in Act one before the storm interlude pulled in the Heldentenor direction, full of the raw keening power of Stuart Skelton.

This is not mere copycat stuff: Clayton brings his own true legato to give the character the tragic nobility of an Otello, able to soar and caress in equal measure. The final “mad scene” was another thing unto itself. Here, Clayton’s realization of the score should redefine the role. Here he seemed to pull on extended techniques more associated with the avant garde – think “Eight Songs for a Mad King” or the aforementioned “Frankenstein!!” – to give a textured account of complete psychic disintegration: pitches bent uncomfortably into microtones; rasping singing that whispers high harmonics; sprechsgesang worthy of Berg’s “Wozzeck.”

Earthly Immediacy

It is a show defined by one role, albeit one that floats on a brilliant ensemble. Bryn Terfel’s Balstrode sees the Welsh bass-baritone in excellent voice, especially honeyed in a sensational Act three duet with Ellen. Terfel plays the part of mediator and conscience well across the piece, convincingly world-weary and exasperated at Grimes’ intransigence. Vocally Terfel’s singing has never seemed closer to his natural Welsh speaking voice than now, with vowels that are distinctly from the valleys. Whether a deliberate choice or not it lends the character earthy immediacy.

Maria Bengtsson is lighter-voiced than some Ellens – the volcanic Lise Daviden has just sung it in Vienna – but she has brightness and clarity in spades, particularly against the sparkling orchestral backdrop of the embroidery scene or the following quartet with the Nieces and Auntie, another searching moment of repose in the action that is directed superbly by Warner. Bengtsson again brings depth and intensity to the characterization, seemingly one of the few people who can both comfort and stand up to Grimes – their duet in the Prologue was sung with a passion that we know, sadly, cannot be.

Jacques Imbrailo – a world-leading singer of Billy Budd – sings Ned Keene. He was in velvety voice, with a clarity of diction that impressed all night. (The singing of consonants really does matter). His over-egged mannerisms are the only sticking point in Warner’s direction. James Gilchrist is more usually seen this time of year narrating a Bach passion or two, and sits exquisitely in the role of the Reverend. John Graham-Hall offers contrast in his more desperate – and rightly outraged – Bob Boles, a man who expresses despair at a community fallen so far.

Catherine Wyn-Rogers’ world-weary Auntie has seen it all, and sings of bitter experience at the hands of masculinity’s failings in the Act two quartet. Alexandra Lowe and Jennifer France offer more acidic but equally knowing turns as the pair of nieces, with costumes that hover between sleaze and threat. Rosie Aldridge’s Mrs. Sedley captures the desperate comedy of her role. Tomlinson is wayward vocally, but the vowels he hits are just as cavernous as vocally, and the dramatic presence is as huge as ever.

The ROH Chorus are given a gift by this opera, though felt under-powered in Acts one and two; nevertheless, in Act three they found terrifying, pert footing, and offered something truly deep and terrible in the closing chorus.

Mark Elder conducts a wiry, expressionist reading of the score. Warner rightly leaves the interludes be, with the curtain down and a brilliant horizon of lighting projected forward. Elder’s reading makes woodwind and brass stand out over strings; the storm interlude is ferocious, the Passacaglia spare and bleak. It deserves lavish praise for its clarity of vision and theatrical craft – a compelling reinvention of one of Britten’s most searching allegories.