Nawal El Saadawi’s 1975 novel, Woman at Point Zero, presents an ‘eve of death-row’ narrative which is a chilling indictment of patriarchal society. An Egyptian woman, Firdaus, has been convicted of murder. The night before she is due to be hanged, she is visited by a renowned female psychiatrist who has become desperate to interview her. Having previously rebutted the psychiatrist’s approaches, Firdaus now agrees to tell her story – a breathtakingly intense tale in which sexuality, love, violence, fear, incarceration and finally death become inextricably and painfully enmeshed, until a woman’s proud dissent against cycles of abuse paradoxically sets her free.

Composer Bushra El-Turk explains that ‘as a Londoner raised by Lebanese parents’, keenly aware of ‘the weight of Middle Eastern traditions and societal expectations’, the theme of imprisonment has been a central theme in her personal and artistic pursuits. Working with an all-female team – director Laila Soliman, writer Stacy Hardy and filmmaker Aida Elkashef, and emphasising the universality of El Saadawi’s text – Bushra El-Turk has created a new multimedia production based on El Saadawi’s novel: a mosaic of documentary film, fiction, narrative, and music from both Western and non-Western musical traditions. Extracts of the opera were work-shopped during the 2017 Shubbak festival, and this production of the fully completed work (co-produced by LOD theatre music) in the Royal Opera House’s Linbury Theatre – part of this year’s Engender festival which has focused on new work by female composers – is the UK premiere following performances in Aix-en-Provence last year and in Belgium and Luxembourg.

Not surprisingly, Woman at Point Zero demands a lot of both its performers and audiences. El Saadawi’s story – essentially a first-person narrative – has been reshaped and restructured to give a voice to Sana, a documentary filmmaker who investigating violence against women, alongside Fatma – whose distressing autobiography still dominates. (The change of name is a pity, perhaps. ‘Firdaus’ means jannāt – paradise, garden, the final abode of the righteous – in Arabic: it’s a boy’s name that belonged to the author of an eleventh-century Persian epic poem, the Shahnameh.) We learn of Fatma’s first experiences of love and sexual awakening – brutally extinguished by an horrific female circumcision; of her abuse by her uncle; of forced marriage to a 60-year-old man; of ‘escape’ into further sexual exploitation, until prostitution gave her a sense of self-determination; of ongoing deceits culminating with her confrontation with a violent pimp whom, in self-defence, she murders.

There’s an expressionist quality about El-Saadawi’s text, as the reader is forced to focus on harrowing episodes related in prose of visual and visceral intensity. One wonders what music might or can add to this? The novel presents long passages that are repeated, and which invite the reader to make connections between the successive, searing episodes, and experience both the tragic inevitability of her narrative and the transcendent power of Firdaus’s final denial of and rebellion against patriarchal dominion. Before attending the second performance in the run, I wondered whether singing – in which words take much longer to communicate – would enhance or dilute the strength of Firdaus’s/Fatma’s tale?

The answer is really neither. The staging is minimal, just a cat’s cradle of wire to evoke both imprisonment and the potential for escape. A camera monitors Fatma’s testimony. The opera lasts barely an hour, and the pace of the narrative is swift, piling up violence and injustice with a speed which makes an undeniable theatrical impact but also makes it hard to take in the horror. If you hit something repeatedly, as hard as you can, with a blunt instrument, it will become numb.

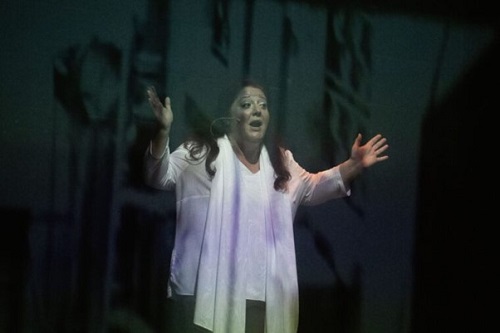

El-Kashef overlays fragmented audio statements and video footage, a choric ‘reality’ which reinforces the staged account but risks distracting us from the two women who are together confronting Fatma’s past, present and future. Dima Orsho’s Fatma is impenitent and impervious, fiercely communicating an integrity that she has preserved despite her suffering. Carla Nahadi Babelegoto’s Sama is a little over-shadowed by such intensity. The vocal lines are declamatory, often literally spoken, occasionally more arioso in style with melismatic flourishes. Both singers are amplified.

What does make an impression is the assemblage of seven instrumentalists on stage, who bring East and West together as cello and Iranian kamancha, accordion and Korean taegŭm, recorder and Armenian duduk spin a magical musical tapestry. Ensemble Zar is conducted with almost fierce directness and economy by Kanako Abe, who creates a hypnotic fluidity of texture and tone. Perhaps this instrumental score goes some way to creating a genuinely transnational context, and to overcoming some of the criticisms that have been made of El Saadawi’s novel: that it reinforces Western stereotypes of Arab culture and reductive narratives about Arab women’s oppression; and that Firdaus’s ‘nihilistic asceticism’ is designed to free herself, not her female sisters, by rejecting reality not seeking to change it.

El Saadawi has written that ‘It’s not a matter of who’s good, who’s bad. It’s a matter of who has the power – who has the power and writes’. At the end of the opera, Sama urges Fatma to appeal against her sentence but the latter refuses: she doesn’t need forgiveness and finally feels free and empowered. Instead, she issues a challenge to Sama, to make something beautiful of her story. As an artist, Bushra El-Turk has taken up this challenge, crafting a cultural and creative collage that aims to persuade us that women who dissent do not die. At the end of the performance, though, I wasn’t entirely convinced that her opera creates characters that are more than one-dimensional or makes complex human relations ‘real’.

Claire Seymour

Bushra El-Turk: Woman at Point Zero

Fatma – Dimo Orsho, Sama – Caral Nahadi Babelegoto; Director – Laila Soliman, Conductor – Kanako Abe, Scenographer – Bissane al Charif, Video designers – Bissane al Charif and Julia König, Costume designer – Eli Yerkeyn, Lighting designer – Loes Schakenbos, Ensemble Zar.

Linbury Theatre, Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London; Thursday 29th June 2023.

All images © Camilla Greenwell