I first saw Tchaikovsky's Eugene Onegin at the Royal Danish Opera when I was a teenager. I fell in love with it, and ended up studying Russian for three years in high school so I could read Pushkin's verse-novel in the original.

Yet while people who know Eugene Onegin often love it dearly, it has never quite acquired the popularity of the Carmens and Toscas of this world. This may be because there is something at its heart that resists the extremes of opera. The libretto is beautiful and subtle, most of it taken directly from Pushkin, retaining the complexity of his verse rather than simplifying it, as librettos tend to. Tchaikovsky himself did not really want his adaptation to be an opera, fearing the conventions of the genre would drown its delicate soul. He refused to allow the Bolshoi Opera to stage it, giving it instead to the Moscow Conservatory, where he felt it would have a more truthful, simple staging, avoiding the easy attractions of glamour and opulence.

The title character is a bored dandy from St Petersburg who inherits a country house. He meets a young woman, Tatyana Larina, who writes him a letter declaring her love, but he spurns her. Years later, he meets her at a high society ball and realises that he, too, is in love with her. But she is now married and has to reject him.

Surprisingly, for a piece that is essentially about the big emotions of youth, the opera is full of melancholy. It does not open with the big, sweeping gestures of an emotional outpouring, but with a fragile drooping line. And unlike many operas, it is not about gods, fairies or faraway mysteries. It is about real people experiencing real things we all go through (except, perhaps, duelling) and can identify with: dreaming, falling in love, facing rejection. There are moments full of sweeping emotion, featuring some of the most seductive music ever written – but Eugene Onegin doesn't try to be sexy. It's not a one-night stand, more a long-term love affair.

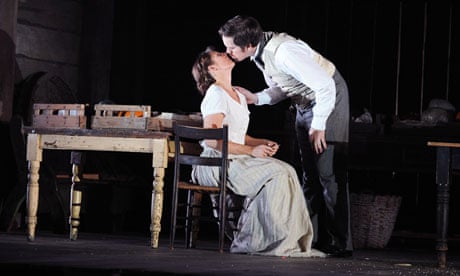

I have always dreamed about staging the work, yet somehow shied away from it. When I was appointed director of opera at the Royal Opera House almost two years ago, I decided the time had come. In my new production, which opens next month, I wanted to build on that melancholic feeling. In Pushkin's novel, the story is told in the past tense, through a third-person narrator. In the opera, Tchaikovsky's music performs that third-person function for us: it lives with the characters, caught in the current of their emotions, but there is also an awareness in the music about impending loss, and thus a melancholy air.

Onegin is essentially about growing up and looking back – sometimes with regret. The story is told in two parts: the first half of the opera is about Tatyana growing up; the second about Onegin doing the same. The two characters mature the hard way – because of things they go through – but they are not judged cynically; rather, we suffer with them. And so my staging of the opera has become about memory, about two people who cannot undo the past; but to understand themselves and their current predicament, they are compelled to go back and relive it.

How do you show someone entering into a dialogue with his or her younger self on the stage? Can a person split in two and then re-merge without the story becoming confusing? These are some of the questions we are currently asking ourselves in the rehearsal room, the challenge being to pull this off on stage without the need for explanations and heavy-handed signalling.

Perhaps the most famous literary example of memories being evoked comes in Marcel Proust's A la Recherche du Temps Perdu, when the narrator bites into a madeleine. The cake immediately transports him back to his childhood; we are all familiar with this feeling of having our memories jogged by some small, unlikely thing. Similarly, in the "seven scenes", as Tchaikovsky called Eugene Onegin (rather than an opera), each scene represents a return to a different chapter of memory.

Real life, and not least our inner lives, is rarely very realistic or rational. With its words, music, movement and visuals, opera gives us a language to express that inner world, to show what it really feels like to be human as we go through life and struggle to understand our emotions and those of others. I hope we can create a language that allows the audience to identify with Tatyana and Onegin as they journey through their pasts, making people reflect on their own lives and memories – just as I did when I sat there as a teenager many years ago, and saw Tatyana write her letter of love for the very first time.

Enjoy an unprecedented glimpse into life behind the scenes at the Royal Opera House on 7 January at theguardian.com/music. Watch over 10 hours of uninterrupted programming, including live rehearsals of Kasper Holten's new production of Eugene Onegin

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion