“It’s a strange thing, to do an interview in which you’re saying: don’t dare to come to my opera!” 58-year-old Italian composer Luca Francesconi is talking about his opera Quartett, which is on now at London's Linbury Studio Theatre. Based on Heiner Müller’s 1982 play (itself based on Laclos's Les Liasions dangereuses), Francesconi describes the piece as a challenge to our ideas of opera, of society, of the dominance of Western thinking, but also to our sensibilities, our psychologies, even our relationships. He talks with a dizzying intellectual and physical energy. “Don’t dare to come if you can't accept that you need to analyse what you do and who you are. This piece is violent, it’s sex, it’s blasphemy, it’s the absence of mercy. The only two characters in the opera are the definition of cynical, they have made a pact that they don’t have to love any more. Love and sentiment are banned, the only thing that’s left and that matters is a kind of chess game with people's souls and bodies. So don’t come if you have problems in your relationship, you might discover something you might not want to! But do dare to come if you can face the reality of how dried up your heart is, how little space there is in your feelings for anything that doesn’t come from being self-defensive, from being totally scared by the world. We are prisoners of our fears. That’s the real last message of this piece, that we can no longer hide our problems – and that we shouldn’t”.

Francesconi pauses to draw breath, and the rest of us pause to catch up with him. There is a passion, even a joy, behind his seemingly defiant nihilism. “You know, I’m not a pessimist at all. I like to live, I like to drink, to eat, to make love as much as possible”. And to write music, too: Francesconi is one of the most fluent of today’s composers, and his music is the result of a fearless creative voraciousness, in which the whole of music history – “from silence to noise”, as he puts it – is the raw material for his musical adventures. Quartett is no exception. Composed for La Scala in Milan in 2011, the piece uses the whole apparatus of a large-scale opera house in ways that threaten to turn the institution and the art-form upside-down.

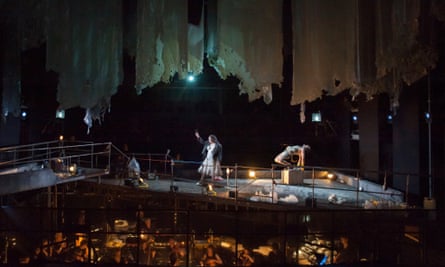

“I felt I was crazy when I said yes to La Scala. When you think of La Scala, you imagine elephants and Egyptians and pyramids. But I had an opera with just two characters, that plays all the way through for 80 minutes! But step by step we created a kaleidoscope of different spaces, like Russian dolls, nested inside each other”. What that meant was a “frame” on stage, a radically smaller space than the La Scala stage, in which the action took place between the characters, a chamber ensemble of live musicians, a set of speakers all around the auditorium through which the singers voices were projected, as well as recordings of a larger orchestra and chorus. “After a while”, Francesconi remembers, the effect of all of these different theatrical, musical and virtual spaces was a kind of existential illusion, in which “the audience had the suspicion that somebody was watching them from a bigger space, so that they were the object of study – a little bit like Big Brother!”

Nervous at first how this conception would work in the smaller space of the Linbury Studio Theatre, Francesconi now feels the London production - directed by John Fulljames - is “more unsettling, it’s more new, it’s more strange, it gives you more emotions”. Not least because the audience are in touching distance of the two singers on a set that’s plunged right in the middle of the auditorium. “The music covers them, it wraps them, it comes from above them and under them – it’s an immersive experience”. He’s right, too, not just in the most sophisticated set-up of speakers and technological manipulations of acoustic space the Royal Opera has ever mounted, but also because the players of the London Sinfonietta are playing beneath the singers’ feet, down there in a dimly-lit bunker conducted by Andrew Gourlay.

And the image of the bunker is an apposite one for a performance of Quartett: Müller’s only indication of the mise-en-scène, Francesconi says, is that the two characters are inhabiting simultaneously, a time before the French Revolution, and after the Third World War, in a prison-like place that’s a blasted relic of whatever society has brought them to the point of their own destruction. That paradoxical time-frame allows the piece to function as a metaphor, Francesconi says, for the beginning and end of the bourgeois era of Western values, an empire that he thinks is coming to an end. “It’s like our financial system”, he says, with that gleeful but nihilistic energy, “which is a locomotive launched at maximum speed against the wall; it’s ridiculous, but nobody wants to change it enough”. The characters in Quartett are named Valmont and Merteuil after Les Liaisons Dangereuses, and this hyper-cynical couple “attack each other like beasts”, Francesconi says, in the course of the opera.

And if there is a kaleidoscope of spaces in which the drama is played out, there’s also a kaleidoscope of stylistic and expressive range in Francesconi’s music. There are moments that might remind you of early music, of folk music, of operatic sentimentality, of modernist austerity; none are direct quotations but come instead from Francesconi’s use of fragments and ideas from the continuum of music history in a “mosaic which is changing every minute and which is extremely shocking”.

And in the middle of all of the desolate extremity of the drama of Quartett, there is even a love scene – albeit played out in a surreal way, as the characters have changed sex and invented new roles for themselves in a warped seduction scene – and there’s a long death scene, too. It’s as if, in critiquing the art-form and contemporary society as he does (he says the La Scala production wasn’t “cruel enough”, and says the Linbury staging will prove “more radical”), he’s also breathing new life into the possibilities for opera in the future. Down in the bunker of the Linbury Studio Theatre, something dark, disturbing, but essential might just be stirring. Get down there – if you dare…

Quartett is at the Linbury theatre, Royal Opera House, London until 28 June.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion