The word "diva" was co‑opted from opera to refer to powerful women in other fields. But, in three shows being staged this autumn, the metaphor is reversed by turning non-singing high-achieving controversial figures into musical leading ladies.

The story of Imelda Marcos, the 85‑year old former first lady of the Philippines, is told in Here Lies Love, a disco-inspired piece by David Byrne and Fatboy Slim, which has its UK premiere at the National Theatre next month; the short and scandalous life of model and actor Anna Nicole Smith (1967-2007) has returned to the Royal Opera House stage in a revival of Mark-Anthony Turnage and Richard Thomas's opera Anna Nicole; and Eva Perón (1919-52), the matriarch of an Argentinian political dynasty, sings and dances with Che Guevara in a new production of Tim Rice and Andrew Lloyd Webber's Evita.

This coincidence raises the question which historical women are worth singing about. It is little surprise that, statistically, Joan of Arc has kindled most creativity in composers, with at least two dozen operas, musicals or song-cycles from talents including Verdi, Tchaikovsky and Bernstein. Fewer, though, would have predicted that so close behind Joan would be Francesca da Rimini, an aristocratic friend of Dante and character in his Divine Comedy, who has subsequently sparked 21 substantial pieces of music, among them works by Rachmaninoff, Rossini and Ambroise Thomas. The 14th-century Galician noblewoman Inês de Castro has also inspired numerous musicians, from Zingarelli to the contemporary James MacMillan.

As Francesca was an adulterer who was murdered, Joan of Arc became a famous fighter before being burned alive for heresy and Inês was decapitated after becoming a king's lover, it can be concluded that it is useful to a musical heroine to have defied the gender conventions of her society and then to die in a dramatic fashion. And, although Marcos has not so far done the latter, the protagonists of Here Lies Love, Anna Nicole and Evita otherwise fit the template of highly sung women.

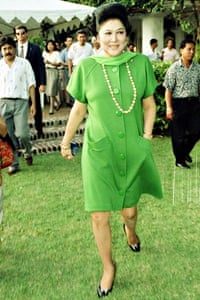

Marcos, Smith and Perón all improbably reinvented themselves from unpromising starts. Born into poor families, they achieved astonishing – and, in each case, legally contested – wealth by marrying powerful or rich men. The three women had all at some point made their living as actors and models and, in their public lives, went beyond even the status of supermodel to become a sort of hypermodel.

These transformations prompt a song in each show. Rice and Lloyd Webber's "Rainbow High" satirically depicts the makeover ("I came from the people, they need to adore me / So Christian Dior me from my head to my toes") that turns Eva from actor into national symbol. And Byrne and Slim, whose Imelda musical has been described as a "disco Evita", seem to be acknowledging the influence in the song "Walk Like a Woman" when Imelda turns from country girl into first lady: "I'm going to learn how to walk like a woman / I'm going to learn how to dress." Thomas and Turnage make these fairytale echoes explicit by including the words "once upon a time" in an Anna Nicole aria.

Both Eva and Imelda were (in common with Joan of Arc and Inês de Castro) Roman Catholics and, in the cult of national mother that Perón and Marcos encouraged around themselves, they were drawing on the iconography of their church's worship of the Blessed Virgin Mary, although perhaps downgrading chastity as a virtue.

Smith, nominally a Baptist, was less religious than the other women but the opera turns her into a quasi-saint by incorporating, in the opening scenes, the words Requiem aeternam dona eis, Domine ("Grant them eternal rest, O Lord") from the Catholic Mass of the Dead; a phrase that Rice and Lloyd Webber had earlier borrowed for a parodic requiem for their diva in Evita.

Most curiously, this trio of divas have all been involved in corpse-related oddities. Perón's body was embalmed and, following a trend set by Lenin, kept on public display. However, following the removal of her widower in a military coup, the remains were spirited away by the army and buried in Milan under a pseudonymous gravestone. When the Perónistas returned to power, Eva was exhumed and displayed for some time on a platform in the home of her husband.

A similar posthumous constancy was shown by Marcos, who kept her stuffed hubby in the basement of the family house in a refrigerated glass casket which, in a photo-op ghoulish even by political standards, she was pictured kissing when announcing one of her bids to run for office. The title of Here Lies Love is taken from a remark Imelda made when contemplating her husband's dead body.

Smith, found dead in a hotel room at 39, was less lucky with her after-death, reportedly decomposing with such unusual rapidity – possibly due to the volume of drugs that the autopsy discovered in her body – that, unusually for an American Protestant funeral, she was displayed in a closed casket. These obsequies are routine, however, in comparison with those of that frequent musical heroine Inês de Castro, whose body was exhumed and crowned queen by her grief-stricken royal lover, with the court reputedly ordered to kiss her decaying hand.

A surprising number of modern historical women have already gone to their operatic reward, partly because the American composer Michael Daugherty incorporates a quartet of strong candidates – Jackie Onassis, Maria Callas, Princess Grace of Monaco and Elizabeth Taylor – in his Jackie O (1997). And Hillary Rodham Clinton, surely a key subject for future biographers of historical women, inspired a mezzo-soprano role in Curtis K Hughes's Say It Ain't So, Joe (2009), which musicalises her failed bid for the presidential nomination.

But, with the exception of Liz Taylor, all of those women come from the US, and – although Evita, Here Lies Love and Anna Nicole were wholly or partly composed by British talent – their protagonists are Argentinian, Filipino and American.

So which women from recent UK history may inspire pieces of musical theatre? The likeliest contenders would seem to be Diana, Princess of Wales and Margaret Thatcher, who have already attracted interest. Thatcher's friendship with the Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet was the subject of Esteban Buch's opera Allies, premiered in Paris last year. And Diana has featured in two operas – Jonathan Dove and David Harsent's TV piece Death of a Princess (2002) and A Lady Dies (2000), a German work by Stefan Hippe and Gerhard Falkner – and a ballet, Diana the Princess (2003), created by the Danish choreographer Peter Schaufuss.

The dance piece was seen in Manchester but none of the Diana shows has yet appeared on a major London stage, possibly for reasons of institutional sensitivity, as the princess's former husband is the patron of the Royal Opera House and the Queen's cousin, Princess Alexandra, has the equivalent role at English National Opera.

During Evita's original London run, from 1978-86, audiences and satirists were tempted to make comparisons with another unprivileged girl turned imperious leader who, for most of those years, occupied No 10. The connection became even more compelling when, in 1982, Maggie went to war with Eva's nation over the Falklands. What an extraordinary operatic moment the clash of the Thatcherites and the Perónistas may one day provide.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion