Some historical periods immediately conjure up the sound made by their orchestras. Think of high imperial Vienna and a Strauss waltz starts to sound, while Edwardian England calls up Elgar. Another is, surely, Weimar Germany. Its characteristic sound is a small orchestra, heavy on the brass and wind, a banjo and a guitar at work. They are making a busy, sour, staccato fugue. Soon a woman will start declaiming in a harsh voice. It’s the sound of Brecht and Weill – and nobody summons up the sound of helpless, furious laughter on the precipice of catastrophe more vividly.

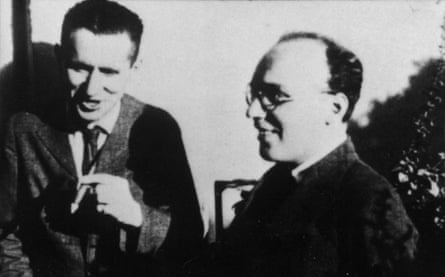

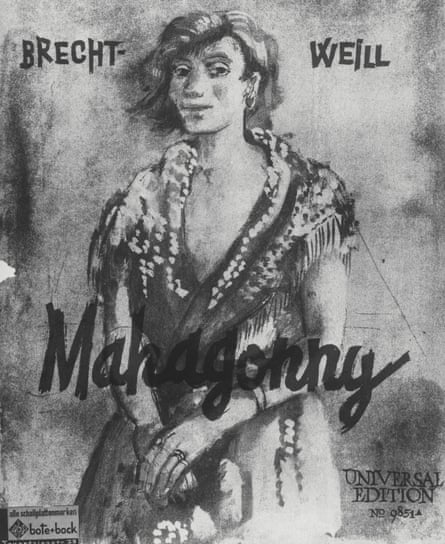

Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny is about to be mounted at the Royal Opera House in London. It’s a rare outing for Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weill’s most extensive and demanding collaboration, itself the culmination of a series of joint works: The Mahagonny Songspiel, The Threepenny Opera and Happy End. The collaboration was problematic – Brecht and Weill came from very different places, and had very different ambitions. What happened after the March 1930 premiere in Leipzig permanently hobbled the piece, and it has never quite recovered. With the exception of Alabama Song, covered by everyone from Gisela May to the Doors, its songs have not seeped into the mass consciousness like Bilbao Song and Surabaya Johnny, survivors of the wreckage of Happy End.

It was performed before the war a couple of times more, notably in Berlin, and then disappeared. Only after the war did opera houses begin, here and there, to revive it as a curiosity. It wasn’t performed in the UK until the 1960s, or in the US until the 1970s, and has remained a rarity, while its distinctive Weimar Republic sound and vision, suitably watered down, took over the world in the form of Kander and Ebb’s Cabaret.

Brecht and Weill’s first collaboration was a setting of nine poems by Brecht, apparently about the founding of a city by pleasure-driven, aimless refugees. The Mahagonny Songspiel, first performed in Baden-Baden in 1927, was a statement of radical theatrical and musical tendencies. The work was staged in a boxing ring. In accordance with the theories of the “proletarian people’s stage” that Erwin Piscator was evolving in Berlin, placards were held up declaring the political programme, and the names and titles of the numbers were baldly announced. The first performance had an argumentative but ultimately rather successful reception. Lotte Lenya, Weill’s wife and a performer in the Songspiel, had no idea whether people had liked it or not until, in the bar afterwards, the conductor Otto Klemperer tapped her on the shoulder and said, “Ist hier kein Telefon?”, one of the lyrics.

Work began almost immediately on a full-length opera, filling out the story of the founding of Mahagonny, its surrender to pleasure, and its collapse. It was interrupted by the quick writing of a radical anti-opera, The Threepenny Opera, which put Piscator’s theories into a form that would prove wildly popular. Brecht and Weill were engaged in a similar endeavour, but the brevity of their collaboration – less than five years – shows how different they really were.

Weill was the extraordinarily gifted pupil of Ferruccio Busoni, the German-Italian virtuoso pianist and composer. Busoni had evolved a theory of what opera ought to be that stood out against the passionate expressivity of Wagner and his followers. His music valued clarity of line, Bach-derived but intensely modern counterpoint, and a harmony that expanded tonality rather than, in the vein of Schoenberg and his followers, abandoned it. Weill studied with Busoni while he was working on his great opera Doctor Faust. He would keep to all these precepts.

Brecht was less disciplined, and his energy took a slightly different form. He wanted theatre to be openly political, even at the destruction of the audience’s pleasure. Troubled by the popular success of The Threepenny Opera among the Berlin public, he killed the chances of the successor, Happy End, by getting his wife, Helene Weigel, to pull out a Communist party pamphlet in act three and read it out, at length. Weill, who later observed that he could not set the Communist Party Manifesto to music, was not consulted in advance.

The tensions in the working relationship were impossible to resolve, and Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny hit another barrier at its premiere. Brecht and Weill may be the sound of Weimar Germany to us, but that doesn’t mean Weimar Germany approved of them. The brownshirts took exception to the piece before it was even performed, and mounted protests outside and inside the opera house. Most of this had nothing to do with the opera itself. Leipzig was the hallowed ground of German musical culture, and the Gewandhaus Orchestra was being soiled by association. Opera was much more central to national life then than now, and Leipzig was near the pinnacle of a substantial pyramid. Weill had started his career as the staff conductor at the opera house in Lüdenscheid, which tells you something: Westphalian towns you have probably never heard of could support the permanent presence of an opera company.

The brownshirts mounted a protest against this “composer who purveys such totally un-German pieces”, as the Völkischer Beobachter, the newspaper of the Nazi party, described him. The violent riot at the premiere, though less famous in 20th-century music history than that at the first performance of The Rite of Spring, had more lasting effects. Police stood inside the theatre at the second performance. A production followed in Kassel, and later one in Berlin, at which the singers were actors and cabaret artists (among them Lotte Lenya), rather than the opera-singers the score seems to require.

After that, it was over. Brecht and Weill left Germany, separately, after the burning of the Reichstag in 1933. Weill ended up in America, where he wrote a series of Broadway musicals, some of surpassing quality, before dying at 50 in 1950 – he was the only Broadway composer then, or perhaps since, to do his own orchestration. Brecht had years in exile before returning, triumphant, to east Berlin, having managed to hang on to his Austrian citizenship and overseas bank accounts. He established the Berliner Ensemble theatre company in 1949, before dying in 1956. Lotte Lenya is perhaps most famous – apart from her inimitable Brecht/Weill performances – for playing Rosa Klebb in the Bond film From Russia With Love, an enchanting cabaret turn in a charming movie.

Mahagonny spoke to its original audience with great violence. Its argument about the consequences of irresponsible pleasure-seeking was almost too accurate for audiences and the new political establishment to hear. What about today? Drinking, eating, fighting, whoring – the way of life in the liberated Mahagonny in the second act – are ordinary sights in quiet market towns come Saturday night, as they were in Weimar Berlin. The consequences of financial collapse that hang over the drama’s fleeing rogues and whores are framed by memories of the very real collapse of the deutschmark not 10 years before. Now, the collapse of a Europe-wide currency seems a possibility, and a production of Mahagonny set on a Greek island like Mamma Mia! would seem to the point.

Nobody is going to immortalise the nation of David Cameron in exquisitely calibrated orchestral fugues. Satire itself is terribly out of fashion, and widely regarded as in bad taste or “snarky”. Nobody would notice today if someone tore up the conventions and manners of opera in the way that Mahagonny and The Threepenny Opera did, for the simple reason that those conventions don’t matter any more, and nobody knows what they are anyway.

But Mahagonny remains a live, dangerous, insulting presence when the other classics of 20th-century protest have been successfully and expensively tamed. Brecht and Weill are still full of affront and offence – and might still provoke a walkout or two.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion