Pink floorboards, yellow chairs, green cupboards and five different sorts of joyously clashing wallpaper: this could be a Richard Jones stage set, especially if you include the garden gnome. We are, in fact, in the director’s south London house – though this meeting is quite a drama. Jones “never” does any interviews and claims to have forgotten how they go.

“If this was for World of Interiors I’d be OK,” he muses, soft spoken, wry and a little nervous. Why the resistance? “Bad experiences.” Why agree now? He evades my question, focusing on the arrival of his cat. The answer – had he given one – might have been: “I guess it’s about time.”

His answer would not be: “Because my new production of La Bohème at the Royal Opera House, replacing John Copley’s adored 1974 version which ran for 41 years, is opening on Monday with a starry young cast conducted by Antonio Pappano.” True to form, Jones won’t reveal anything about his new production. He thinks directors have nothing to say and the work should speak for itself. He hates the idea of “witnessing process. Cameras in rehearsal rooms? No-o-o.”

Born in London in 1953, Jones doesn’t speak much of Damascene moments and doesn’t tell anecdotes. Did he see much opera as a boy? “A bit. I probably went with my mum.” After comprehensive school he studied anthropology at Hull University where he did once spot, without quite knowing who he was, its famous poet-librarian Philip Larkin. “If it’s OK we won’t talk about education.” It’s OK. We don’t.

After university, he put his energies into being a punk. “Or rather, I had a boyfriend who was a punk. We watched the Sex Pistols and hung out in Covent Garden, which was a very different place then, quite scuzzy, badly lit … ” A good musician, he worked as a jazz pianist, playing in bars and for West End shows, which gave him valuable insight into the mechanics of theatre. He performed, too – “I’ve never said this before” – at the legendary Blitz club in Great Queen Street, cult home of Boy George and the New Romantics c1980, so hip it once turned away Mick Jagger at the door.

It was “my own bohemian period. I was a bit aimless. There was still agit prop in those days – theatre as agent for social change, a pretty risible idea now. I loved the tough, cool productions of John Dexter, and classical ballet, too. Still do. Both showed you exactly where the eye should look – perfect tutorials for a would-be director.”

After initial forays in rooms above pubs, Jones made a mainstream theatre splash directing Ostrovsky’s Too Clever by Half at London’s Old Vic in 1988. At the same time, he turned to opera. His version of Prokofiev’s Love for Three Oranges at Opera North and English National Opera the following year, in which scratch and sniff cards were handed to the audience, was deemed irritating and intriguing. Here was something novel, zany and outrageous.

Then in the mid 90s came Wagner’s Ring cycle at the Royal Opera House. Uneven but intelligent, the production also struck many as inept and provoked bilious headlines. Jones is in two minds about it. “I’d love to have another go at The Ring. Nearly 25 years on, I can safely say aspects of that production were catastrophic.” Music director Bernard Haitink was not sympathetic to Jones’s “naked” Rhinemaidens fattened up with Latex body suits, or to Wotan carrying a one-way sign for a spear, or Brünnhilde wearing a brown paper bag over her head. The difficulties were well recorded.

Yet Jones was never out of work, at home or abroad, directing productions in Germany, on Broadway (briefly, with Titanic the musical) and at Glyndebourne. His style is unmistakable, whether in the human zoo in Berg’s Lulu at ENO (2002), the inflatable horrors of Mark-Anthony Turnage’s Anna Nicole at the Royal Opera House (2011) or the exquisite, white-starched serenity of Suor Angelica, part of Puccini’s Il Trittico also at Covent Garden (2011).

“You liked Suor Angelica? I’m glad,” he asks, surprised, as if no one else had. It was universally acclaimed. “I was worried about the nuns. That bit at the end when the madonna and angels come on… But it seemed to go OK. It’s all there in Puccini’s stage directions. They are so detailed, as they are in Bohème, too. Tony Pappano is amazing, very attentive to all that.”

He has collaborated with Pappano many times, calling him “a fantastic colleague and very funny. It’s terrible if a conductor doesn’t have a theatre gene. A lot don’t.” He won’t say which, but points to Edward Gardner and Vladimir Jurowski as among those who do have it.

Jones agrees that after four decades he has established “quite a monotonous method” of directing: “Backstory, biography, where the action is, what the temperature was, what they’re trying to achieve in a scene. I like clarity of intention. It’s not a crime to read Stanislavski. I try to be quite rigorous. It’s hard. But these are top professionals, a brilliant team with none of that ego that can cripple things in rehearsal. Three weeks in a production room and then a tough birth … ”

And then there’s the pressure of replacing the Copley show, a hallowed Royal Opera ritual that enjoyed 26 outings and several hundred performances. “I can’t think about it. The other day I took a peek – on DVD – at the beginning of Act IV of the old production. Then I panicked and turned it off. Not out of disrespect ... I know it’s given people great joy.”

A member of the public asked Jones, perhaps hopefully, the other day whether his Bohème would be traditional. “I wasn’t being disingenuous” – a favourite Jones word – “but said, ‘Please can you tell me what traditional means in this context?’ You have to try to do it for someone who’s never seen the show. Even the performers come with an idea of how it should go, an imago, so they may resist what I suggest. We’re currently having some discussion over … the ending.” He skilfully manages not to spill the beans. “It’s a lot easier doing something like Anna Nicole – a new piece, a blank page.”

He considers La Bohème bullet-proof, “like A Streetcar Named Desire. Some pieces just are.” He’s too canny to mean this in terms of his own production. It’s a practical observation. Other great operas lack that indestructible quality. “There’s a lot of plate-spinning in, say, Don Giovanni, where you have to convince the audience they’re watching a dynamic show. It’s not dynamic in the same way as La Bohème is.”

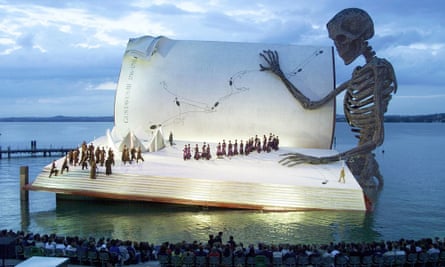

He has directed Puccini’s 1896 masterpiece, based on Scènes de la Vie de Bohème by Henri Murger, once before, in Bregenz. That big outdoors rock’n’roll retelling of the story of the dying Mimì and the poet Rodolfo “didn’t work so well”, he concedes. For the new ROH production, he will rehearse the first of three casts, then hand over to a team of staff directors who will continue it until Christmas. Meanwhile, Jones will head to the Almeida theatre to direct The Twilight Zone, based on the early 1960s American sci-fi TV series “dealing with aliens, nuclear war, anxiety, all rather prophetic” – and all rather up Jones’s psycho-fantastical street.

For an interview sceptic, he has been generous and obliging. As we wind up, he bursts into a paean to La Bohème. “It’s a fantastic play. It’s through-composed. The text is faultless, it’s economic, propulsive. It’s got really ingenious characters. Everyone’s ambiguous morally. Everyone’s good and bad. It’s almost like Chekhov. It’s about the young, the vulnerable. It’s about people falling in love, squabbling, parting, reuniting. Then at the end something devastating happens. That’s an amazing theatrical formula. It makes people’s hearts joyful, and it breaks their hearts. That’s what it’s there for.”

That’s quite a sell, and still his production secrets are safe. Our two-hander drama over, Jones goes off to feed his tabby, quite prepared for whatever sharper claws are out on Monday night.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion