Australian theatre director Adena Jacobs says her new production of Salome – opening at the London Coliseum later this week – will be “mythic, feminine and brutally contemporary”. Richard Strauss’s 1905 opera, based on Oscar Wilde’s play, was always contemporary, always brutal. Any tale involving a severed head, a pathological, nubile virgin and her perverted stepfather runs that risk.

It is unlikely Jacobs will recreate the shock that Strauss’s opera – and Wilde’s play – generated more than a century ago. The opera premiered in Dresden on 9 December 1905 and, despite – or because of – its lurid subject matter, was immediately taken up by other German-language houses. Before the first British production, in 1910, the Daily Mirror devoted a front page to the scandal of an opera about the girl who demanded the head of a prophet, then spent the final 10 minutes kissing her bloodied trophy. Censors objected to the staging of a Bible story. Bishops frothed at its necrophilia, blasphemy and general revoltingness. The Metropolitan Opera, New York, suffered its first budget deficit after cancelling the US premiere run: John Pierpont Morgan, the fabled banker, was on the board at the time and yielded to his daughter’s plea for subsequent performances to be banned. It still provokes shock. As recently as 2002, a staging directed by Atom Egoyan for the Toronto Opera Company caused an outcry for perceived antisemitic elements.

Taken from a few lines in the New Testament, the plot describes events in first-century Galilee. Salome is the daughter of Herodias and stepdaughter of her husband, Herod Antipas. The head that Salome demands in return for dancing at Herod’s birthday feast is that of John the Baptist (Jokanaan in Strauss’s opera). He is imprisoned downstairs in the cistern, shouting out his moral apothegms with limited charm, which nevertheless dazzles Salome. For the first time in her life, she experiences love and wants it, alive or dead. Even her depraved parents are horrified: Herod condemns her to death.

Leaping forward a millennium, bypassing Salome’s darting, archetypal appearances en route – as huntress or witch in medieval imagery, as a sultry temptress in renaissance paintings by Caravaggio and Titian, as a figure in sculpture, poetry and plays – her moment came at the end of the 19th century, especially in the decadent culture of fin de siècle France. Wilde was only the last of a stream of writers, from Heinrich Heine and Jues Laforgue to Stéphane Mallarmé and Gustave Flaubert, who took inspiration from this potent female, a subject ripe for misogyny, sadomasochism and daring eroticism.

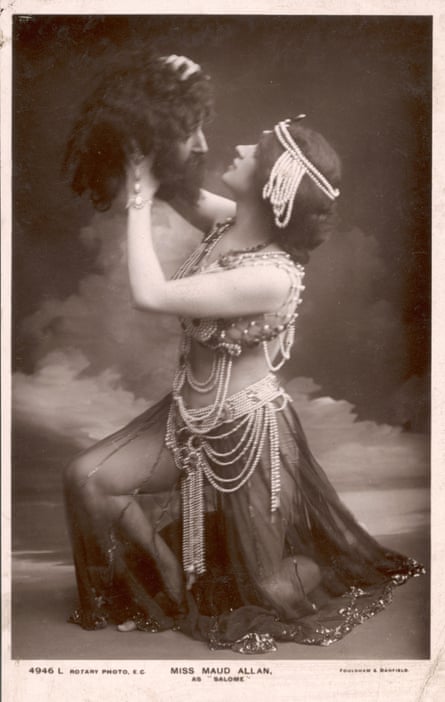

A parallel craze developed for Salome dancers, often performing in music halls. While men may have salivated, women enjoyed the freedom of performing with very little on, among them Loie Fuller and Mata Hari. Most prominent was the Canadian Maud Allan, who became embroiled in a court case in 1918, after an article by the British MP Noel Pemberton Billing entitled The Cult of the Clitoris, which was rife with implications of lesbianism and German conspiracy.

Wilde, however, must take credit for introducing the dance of the seven veils – probably originating in ancient tales of the Babylonian goddess Ishtar – which lies at the heart of Strauss’s opera. It is the moment when slumbering audiences sit up. This luscious, lubricious orchestral interlude quickens into a frenzy as each veil is cast aside and leaves Herod panting.

The Scottish mezzo-soprano Allison Cook is singing the role for the first time in the English National Opera’s new production. Having already sung the Duchess of Argyll in Thomas Adès’ Powder Her Face, another wild woman associated with headless men, Cook could be said to have form.

“This has been a long time in the pipeline,” she says. “The sheer stamina you need, technically, to sing it safely and not damage your vocal cords is like preparing for a marathon. I’ve been singing it every day for four months. And I’m only talking about the music, never mind the rest of it.”

Strauss once described the role as “a 16-year old princess with the voice of Isolde”. Salome has to have the vocal heft to rise above a large orchestra. She also has to keep focus and energy in reserve for the demanding solo finale. This has caused problems in casting. Strauss’s first Salome, Marie Wittich, refused to dance or kiss the severed head on grounds of decency (her own), though eventually agreed to perform, with a local ballerina substituting her in the dance of the seven veils.

These days, there are enough singers game and physically able to do it. One of the first was Maria Ewing at the Royal Opera House, London, who danced until she was naked in a steamy, but otherwise well-clothed, production directed by her then husband, Peter Hall, in 1992. One reviewer mentioned her in the same breath as a Vegas pole dancer. Yet, you don’t have to be a prude to think twice about dancing naked in front of a couple of thousand beady-eyed opera lovers. The American singer Deborah Voigt, interviewed in 2006, said she would not have taken on the role had she not had gastric bypass surgery to assist her weight loss.

The most memorable of recent Salomes is the Finnish soprano Karita Mattila, whose orgasmic carryings-on with the head in the final monologue “like a ravening animal”, in 2003, left the Guardian critic overwhelmed.

How different will a production directed by a woman be? Jacobs, whose Melbourne-based company, Fraught Outfit, makes a speciality of tackling biblical and classical mythologies, says this staging will “present a dreamlike journey through Salome’s psyche, in a claustrophobic space in which female desire replicates the violence of the patriarchal world”. Given that this is a central tenet of the piece anyway, we must wait to see what this means for Jacobs, or for Cook’s performance.

Cook won’t reveal much: “But I will say it’s very beautiful and, given the director, designer and lighting designer are all women, undoubtedly it’s being seen through female eyes but not in a militant way at all. There’s a softness in the approach.” She is enthralled by Strauss’s rapturous, ingenious score, which made him his fortune. “It’s so rich and lush, like a pool of melting dark chocolate. Yes, it’s horrific in parts,” says Cook. “It’s intense, uneasy, psychologically complex, but there are so many moments of sheer, ravishing beauty.”

Will Cook dance? “I won’t shimmy and I won’t do a fandango. I’ll certainly dance but I don’t think anyone will be inviting me on Strictly.” And will she take all her clothes off? “Buy a ticket and find out,” she says, resolutely buttoned up, revealing nothing.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion