Fine singing overcomes heavy-handed Freudianism in BLO’s “Flying Dutchman”

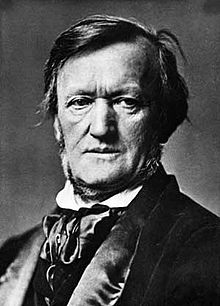

Richard Wagner’s original version of “The Flying Dutchman” was performed Friday night at Boston Lyric Opera.

The Boston Lyric Opera is ending its season by presenting a retooled version of Wagner’s The Flying Dutchman, which opened Friday night at the Shubert Theatre. In reality, this 1841 critical edition is the original version composed for Paris, which was never performed in Wagner’s lifetime, and predating Wagner’s additions that clarified the opera’s focus on love and its salvific powers. This edition, as interpreted by the BLO, is dark and ambiguous. Aided by strong singing and incisive conducting, Wagner’s opera sheds its romantic trappings to reveal a work that seems at once modern and psychological.

The opera’s name comes from the eponymous myth, about a sea captain, the Flying Dutchman, cursed to sail without rest unless a woman chooses to love him faithfully. By accident, the Dutchman meets fellow captain Donald, who agrees to betroth his daughter Senta to the Dutchman. Senta, it so happens, obsesses over the legend of the Flying Dutchman and dreams of being the woman who saves him. She agrees to the marriage—but when the Dutchman overhears her spurned suitor George reminding her that she had pledged herself to him, the Dutchman considers himself lost. To prove herself loyal, Senta commits suicide. Here, the BLO’s version ends; in traditional versions, Senta and the Dutchman ascend to heaven, saved by her sacrifice.

BLO has decided to frame their production of The Flying Dutchman around Senta, her troubled mental health, and her even more troubled relationship with her father. This new focus is signaled by younger versions of Senta wandering the set, ignored or unseen by those actually on the stage, and by pantomimes that include Senta suffering migraines and smearing blood on her hands.

There is some heavy Freudian business going on, especially when, late in the opera, the Dutchman and Donald are seen to sing the same lines. It is a fascinatingly Gothic and refreshing interpretation, but too often a heavy-handed one.

Regardless the singing propelled the drama, and once again the BLO has assembled a fine cast. Allison Oakes as Senta anchored the opera. Her warm soprano cut cleanly through the orchestration during Senta’s passionate declamations, and her softer singing was poised and beautifully phrased. Her Senta was one of those performances that grew steadily over the course of the evening.

Alfred Walker as the Dutchman seemed, at the outset, poised to be the standout of the night. His huge bass-baritone easily filled the house and thundered through the Dutchman’s first scene, in which the accursed captain bemoans his plight. But though Walker was never less than expressive, there was something too generalized and even unfocused about his Dutchman, perhaps inevitable when playing a character that might actually be a figment of someone else’s imagination.

Chad Shelton’s spurned George is the smallest of the four leads, but plays a crucial role. It was the warmth and spontaneity of Shelton’s portrayal that threw open the human dimension in a production that was becoming dangerously preoccupied with its own metaphysics. Not only did Shelton’s sizable tenor dispatch Wagner’s music with aplomb, he colored his voice expressively to differentiate between George’s ardor and foreboding.

Gregory Frank’s Donald was, like his character, the most mysterious of the evening. Early on, there seemed to be dry spots in his instrument, but he went on the produce some of the most penetrating sounds of the evening. His stage presence was dynamic, and his portrayal round: this Donald was what the music made of him, a sea captain cheerfully willing to sell his daughter for riches. In the small role of the Steersman, Alan Schneider provided beautifully shaped singing, as well as excellent diction.

David Angus’s direction also deserves praise. His orchestra is not Wagnerian in the usual sense of the word, but under Angus’s direction, the smaller scale becomes an asset. Wagner’s numerous orchestra effects are thoroughly essayed, but here the orchestra is in service of the singing and the drama (and the chorus, which sang like a veritable force of nature). Angus tightens the tempo and shapes dramatic climaxes so that we hear an opera not about love, but about the harrowing power of human passion.

The Flying Dutchman continues through May 5 at the Shubert Theatre. blo.org

Posted in Performances

Posted May 04, 2013 at 4:34 pm by amy nicholls

saw the opera last night the music was sublime but after the first fifteen minutes I closed my eyes so I wouldn’t have to watch the stage….this production was beyond ponderous…why was the Dutchman in a silver trenchcoat…who were these red dressed girls wandering the stage …why were people wandering in and out and off stage right and on stage left, and it was too painful to open one’s eyes…..so I just closed them….the music was sublime, the soprano breathtaking, the voice of Donald superb…..but the set and the staging was ridiculous….felt like I felt when I watched a French production of Xerxes in Paris 15 years ago…..and believe me I love contemporary works when staged well–like Nixon in China or Faust at the Met. And my friend says that’s it, no more Wagner for him no matter what I say. Shame…I knew what they were trying to do, and it just was too heavy and dark….even for Wagner