Children may be more open-minded as audiences than the adults who accompany them but they expect certain routines: rude noises, wiggly bottoms, a man with a knotted handkerchief on his head, clumsy walks, visual transformations and at least one explosion which makes them jump though they feign nonchalance. Julian Philips's How the Whale Became, with a libretto by Edward Kemp based on animal creation stories by Ted Hughes, has all these elements and more. The recipe works in parts.

The Royal Opera House describes this new work as a "family-friendly opera" for the over-fives. I would say over-sevens, with prior knowledge of the Hughes stories, will gain most pleasure from it. With much of the text inaudible, it was hard to follow except in broad, how-do-we-become-who-we-are outline. Given the Linbury acoustic, mic-ing might have helped, even if it goes against the operatic grain. Natalie Abrahami's staging, exquisitely designed by Tom Scutt with the kind of lavish detail that gives a child something to examine in the slow or boring bits, places the action in the round, as far as the Linbury allows.

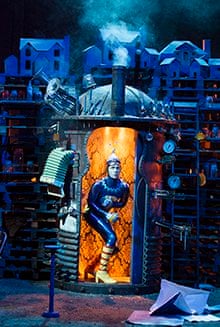

It all gave the illusion of being ramshackle and risky, like the teetering constructions children love to make stuck together with glue and hope. Here was a world in miniature: pint-sized houses with gardens producing king-sized vegetables in satisfying rows, and lights that glow across the hillside as the sun goes down. Scutt won a best set designer award this year for Constellations at the Royal Court, and on this evidence you can see why.

Opera for children – rather than opera to be performed by children, a different matter entirely – is no easy genre. Oliver Knussen's Sendak double bill of Where the Wild Things Are and Higglety Pigglety Pop! has gem-like perfection. Jonathan Dove's The Adventures of Pinocchio (2007), to a libretto by Alasdair Middleton, won widespread praise, and The Firework Maker's Daughter (2013) by David Bruce and Glyn Maxwell, based on Philip Pullman's fairytale, had its fans. So too will How the Whale Became, even if others will want more roar and sparkle and digital sleight of hand.

A small ensemble of musicians and singers play, act and clamber over four large pallet structures, vanishing inside a Tardis-like "making machine", playing a honky-tonk piano painted in bright colours, or employing kitchen utensils to make imaginative percussive sounds. The accordion (Rafal Luc) has a dominant aural role, but so, too, under the music direction of Geoffrey Paterson, do woodwind, toy and grand pianos, garden hose and dustpan and brush. A ginger cat (Isla Mundell-Perkins) plays the violin beautifully in the most extended music of the evening.

With a coloratura frog and a brilliant peacock able to leap from tenor to falsetto, the score offers every variety of operatic voice, mostly in short bursts rather than songs. This was not (phew) an audience participation kind of event and there were no children in the cast. Perhaps that was a missed trick: seeing a talented child perform with adults can hook the young into a performance, as with the boy in Menotti's Amahl and the Night Visitors (1951). That piece about a disabled child miraculously cured may be simple and sentimental and mostly in C major, but it works – and still appears in lists of "most performed operas in the world".

In How the Whale Became, a joyful cast of five took on multiple roles: Fflur Wyn as Girl/Polar Bear/Cow, Donna Lennard (Frog), Andrew Dickinson as Boy/Wild Bull, James McOran-Campbell as Poor Thing/Leftovers and Njabulo Madlala as Whale/Elephant. Charm never toppled into mawkishness. There were plenty of children in the audience who seemed absorbed and attentive, rather than awestruck or amused. The first half lasts nearly an hour – longer than the entirety of Amahl. That would have been enough for many.

Luckily I was able to consult my friend Charles Rowley, 7, from Bow, east London, for the low-down. At the interval he said: "I think it was probably perfect." Pushed, he added: "If I were old I wouldn't like the noises." (It's OK, Charles, they were quite fun.) What about the singing? "It was perfect. Well not the bit the lady did which was wobbly – I don't think she could handle it." At the end, before rushing off to write his review, or maybe go to bed, Charlies summed up the second act: "It was a bit the same. It was OK. I liked the first half better. But I liked it all a lot."

Charles might have been quite taken with Remember Me: A Desk Opera, an opera in miniature by the composer and sound artist Claudia Molitor, co-commissioned for Sonica and Huddersfield contemporary music festival with support from the PRS for Music Foundation and the RVW Trust. Given the pittance composers earn – maybe £3,000 on average for a commission that might take a year to write – these funding bodies deserve mention at least once a year. They are the invisible backbone of British contemporary music.

First seen in Glasgow last year, Remember Me featured in this year's ever eclectic Spitalfields Music winter festival. Molitor's delicate, elusive piece combined her inheritance of a desk from her grandmother with two doomed operatic heroines, Dido and Eurydice. The composer's own wan, ethereal presence guided proceedings, in which rose petals were scattered on the floor, and video was projected on her outstretched scarf. Small objects were moved around a desk to tell stories. The pre-recorded music, fragile yet strong, was strange and unsettling. Molitor whispered a message to each of us as we departed one by one, a distorted version of Dido's Lament sounding in our ears as if across a windy plain. Charles would have grasped it all instantly.

Star ratings (out of 5):

How the Whale Became ★★★

Remember Me: A Desk Opera ★★★

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion