Just as you know the difference between Hamlet and the gravedigger from speech alone, so in Don Giovanni you can tell who's who by the music they sing. Key changes and style reflect class and emotional status: the wayward nobility of Donna Anna versus the coquettish immediacy of the peasant bride Zerlina. Any number of post-doctoral theses will debate the point for you, but in the theatre let instinct be your guide. So acute is Mozart's ear for drama, you understand each twist and turn of the plot, every shift from minuet to canzonetta, from major to minor, simply by opening your ears.

This is just as well, since Kasper Holten's new staging for the Royal Opera House strips away much of the social nuance and has the characters roaming around a two-storey house with much upping and downing of staircases – a Piranesi game of facade and interior. Es Devlin's handsome, blank set is swathed and reinvented endlessly by Luke Halls's video designs. Scribbles and squiggles, drippings, seepings, tricklings and oozings cover all beautifully and kaleidoscopically.

The downside of all this manic visual activity is to distance and flatten the relationship between characters, as well as to challenge the eye as to where to look. If you had no signs of attention deficit at the start of the evening you may require medication for it by the end. Seeing the production on the second night, and sensing already via social media that audience response had been divided, I was expecting excess. A recent Don Giovanni (Garsington's in 2012) opened with female bondage and leather, from which the only direction is down.

Instead Holten has avoided gratuitous sexual gesture. In an effort to reconcile Enlightenment mores with modern-day attitudes, he has given the women more complicity in their own seduction. No longer can we believe they are as innocent as they protest. Anna is as furious at being rejected in love as she is grief-stricken at realising her lover is in fact her father's murderer. Elvira is touchingly loyal to the villain. Zerlina is downright naughty, playing with fire then pretending she didn't light the match (she pulls open her dress to suggest more rapine violence than actually occurred). Controversial though this might be given current attitudes towards sexual coercion, it enriches the story.

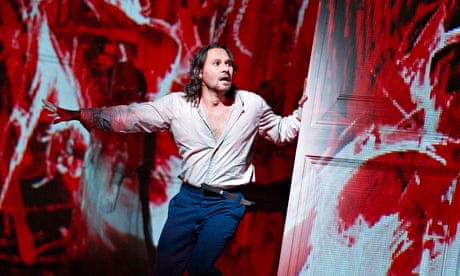

The cast is generally secure rather than exciting. As the Don, the Polish baritone Mariusz Kwiecien sang with assurance but did not fill this larger-than-life role as, say, Bryn Terfel once did. Alex Esposito charmed as Leporello, but neither he nor Kwiecien raised the chilly laughs their master-servant relationship can provoke. The Swedish soprano Malin Bryström's Anna, impassioned but weak at the top, and the French soprano Véronique Gens as the sadly obsessive Elvira, brought dignity rather than rage to their roles. Elizabeth Watts sparkled in her debut as Zerlina. The ROH orchestra, under Nicola Luisotti's usually brisk baton, played superbly as ever and the chorus was strong. There was no dinner with the "stone guest" or hellfire to add excitement at the end. Instead the Don writhed, alone and finally beaten, in the inferno of his own deluded psyche. With so much of the narrative stripped away, this staging might be puzzling for a newcomer. Try it first at the cinema on Wednesday. And take note of the women's fabulous costumes by Anja Vang Kragh, exquisitely made as if crafted from melted wax and spiders' webs, each a work of art.

The other long-awaited event of the week was the world premiere, given by the London Symphony Orchestra and conductor Antonio Pappano, of Peter Maxwell Davies's Symphony No 10. Opening with Elgar's dreary In the South (even some lovely flute and viola solos could not make this work sound vivacious), the LSO then provided sensitive, poised accompaniment to Maxim Vengerov, soloist in Britten's Violin Concerto. Vengerov first played and recorded this work early in his career. He tackles its technical horrors with absolute command and ease. It was a thrilling performance.

Given the supposed curse of Ninth symphonies – for several composers it has proved their last endeavour – anyone tackling a 10th earns nervous respect. Maxwell Davies wrote his under what he thought was sentence of death, completing much of it in hospital. He has since, mercifully, recovered, and was at the Barbican last week to hear the LSO, who commissioned it, give a lustrous performance of the four-part work inspired by the life of the Italian architect Francesco Borromini (1599-1667).

The work opens gracefully and slowly, a truncated horn cry blurting over the soft quivering of two marimbas. The first section moves in upward bursts of trumpets, piccolo, metallic percussion, joined by strings and eventually some massive brass chords. "I feel I'm building a church in music," writes Maxwell Davies, and that sense of construction is precisely how it sounds. After the urgent choral statements of Part Two, the third section is rich in instrumental detail and some of the brilliant aural effects familiar from Max's prodigious oeuvre. Part Four records the moment a despairing Borromini contemplated suicide, throwing himself upon his sword, then crying for help. Vocal and purely instrumental passages alternate, with dense, choral passages passionately sung by the London Symphony Chorus.

The large orchestra makes keen use of low woodwind and brass – contrabass clarinet, contrabassoon, bass trombone and tuba – and the percussion writing, requiring six players, delights in the use of bells, gongs and flexatone alongside crotales, temple bowl and more. This immediately approachable, substantial work ends with chorus and baritone soloist (Markus Butter) in slow, hushed prayer, uttering the name of music's patron saint, Cecilia. Creativity, mortality and renewal: this was the collective message that imprinted itself on our hearts as Max took his bow and beamed at his cheering audience.

Star ratings (out of 5)

Don Giovanni ***

Peter Maxwell Davies Symphony No 10 *****

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion