A symbolic fairytale opera about fertility, pickled in the imaginations of two middle-aged men, is bound to have problems for a modern audience. In Richard Strauss's Die Frau ohne Schatten, with a libretto by Hugo von Hofmannsthal, the woman of the title has no shadow, a sign of her barrenness. Eventually, after many convolutions including flying fish, a choir of unborn children and some exceptionally good behaviour, she is blessed with offspring. Try explaining that to the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority.

Strauss's four-hour epic remains a rarity, not so much for distaste over the plot, though that too, but because of the perils of casting it: three explosive, demanding roles for women, and a high tenor part to challenge the most athletic vocal capability known to man. In the Royal Opera's grandiose new staging the cast – led by Emily Magee, Johan Botha, Michaela Schuster, Johan Reuter and Elena Pankratova – rises to the challenge of these impossibly wide-ranging parts, scaling the highest and lowest notes with barely any signs of strain. This co-production with La Scala, Milan, sharing most of the same singers, is a significant achievement in Strauss's 150th anniversary year.

Musically, under the fervent baton of Semyon Bychkov, it thrills. The enormous Royal Opera orchestra, an army of percussion spilling out into side boxes and amplified with additional brass, organ, low woodwind, wind machine and glass harmonica, shine stupendously. Fortissimo passages, of which there are many, made the floor shake. Even Wagner sounds pallid in comparison.

Not all is noisy. The chamber writing – solo instruments embroidering filigree sounds around each other, strings divided to enrich the texture – sounded magical. Those passages alone, as in the sextet from Capriccio, could define Strauss's musical style.

Reading on a mobile? Click here to view

Despite Christian Schmidt's handsome and careful designs, Claus Guth's production fails to clarify. The Royal Opera's last, long-lived Frau, directed by John Cox and new in 1992, had psychedelic, bright designs by David Hockney. The effect was helpfully hallucinogenic, effectively blurring the story. A recent Edinburgh festival staging turned it into a kitchen sink drama complete with washing machines and refrigerators. Both extremes worked.

Guth, making his ROH debut, underlines the sadosexual aspects of the story. Rather than let the fairytale do its work, he spells out its darkness, in case you miss it. The empress (a majestic Magee), writhing in bed a good deal, apparently dreams events as they unfold. Her nurse (Schuster), evil in black and with a sausage-shaped top-knot, is omnipresent and demonic. Barak's wife (Pankratova), also childless but unlike the empress bursting with earthly desires, is dressed identically to add to the confusion. A gazelle – the empress in her former, spirit life – a falcon and a magnificent ram haunt the stage. Many people run in and out wearing top hats and black wings, looking gothic.

When the children finally appear, they wear baby gazelle heads. It's Goya's Witches' Sabbath, Beatrix Potter and Magritte rolled into one. To enjoy this extraordinary work, you have to rise above the story – if you can find it. Strauss praised Hofmannsthal for his economy of text. Yet for most of us it remains frustratingly opaque. It is also, and this is part of Strauss's paradoxical appeal, magnificent, enthralling and one of the best scores he ever wrote. Explain that if you can. Listen to the live broadcast on Radio 3 Saturday 29 March from 5.50pm.

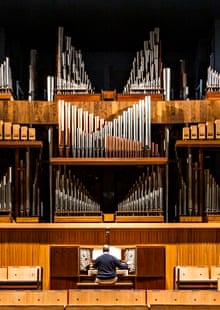

This week's other outsized, or oversized and overlong, event was the relaunching of the Harrison & Harrison organ at the Royal Festival Hall after nearly a decade of restoration. The hall was packed, expectations high, four top organists lined up to play: John Scott, Jane Parker-Smith, Isabelle Demers and David Goode. Above the console, a spectacular phalanx of thousands of pipes, from the size of a pencil to the height of a tree, gleamed in readiness. Foot pistons and swell pedals, bellows and pumps, stops and divisions, tierce, dulzian, diapason, vox humana – for non-players the organ is another and exotic country.

Indeed its presence is so astounding, visually and aurally, it requires no ketchup, spice or chutney. The instrument's grandeur – especially in works by Franck and Dupré – was never in doubt. If only we had had more time to hear it. Galas are about thanking donors – some 60,000, listening on Radio 3 if not in the hall – and creating an "event". So trumpeter Alison Balsom joined in with a Bach arrangement. World premieres by Peter Maxwell Davies and the late John Tavener were engaging but required, in Max's case, a charming children's choir and brass ensemble, and in Tavener's an adult choir. Only five works were for organ alone. Fortunately the Southbank's Pull out All the Stops festival lasts until June. You can take organ lessons, learn about pipes or go to a Wurlitzer tea dance. Do better. Savour the instrument at leisure in a solo recital. Let nothing distract you from the glory of this giant beast.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion