Moses und Aron (Welsh National Opera)

The ineffable nature of faith and the infallibility of belief are the two ideas that form the crux of Schoenberg’s monumental, unfinished opera Moses und Aron. Composed to his own libretto, the composer’s exploration and exposition of these two fundamental cornerstones of human nature stands as one of the most important operas of the twentieth century. Given the complexity of the score and the huge demands it makes on any company bold enough to stage this work, performances are rare.

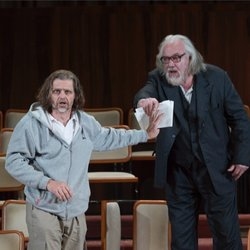

© Clive Barda

The last staging in London was by The Royal Opera in 1965, so this pair of performances by Welsh National Opera gave those opera goers with an adventurous streak a rare opportunity to experience Moses und Aron first hand. Needless to say, the demands the composer makes on the audience are nearly as great as those on the performers. Two and a quarter hours of serialism and Sprechstimme require a huge amount of concentration on the part of the listener, and whilst this compositional style can often come across as arid, Schoenberg creates such an arresting palette of orchestral colour within which the choral and vocal lines intertwine that the opera becomes a living, breathing d0rama.

WNO turned to Stuttgart for its mise-en-scene, with Jossi Wieler and Sergio Morabito’s modern take on the work mercifully sparing us of a Cecil B DeMille faux biblical setting They choose instead to tell the story as a modern-day battle of wills and ideologies played out in Anna Viebrock’s striking single courtroom set. Here a dishevelled, almost Beckett-like Moses pits his wits against a sinister group of followers and his brother, Aron, before setting off on his travels to receive the word of God.

Left to his own devices Aron begins the insidious process of turning the crowd against God and Moses, before Moses returns only to destroy the commandments. The contemporary metaphor that the directors so skilfully portray is how we react to, and perceive, the notion of faith and what it means to be a believer. Despite the fact that their approach at times felt too sterile in the first act, the staging remains full of deft touches. Given the setting, the sacrificial orgies and building of the golden calf are banished; instead Aron treats the assembled throng to a skin flick, which the crowd watch gazing out into the audience as if we were behind the screen. It works brilliantly, especially given that there’s enough orgiastic excess emanating from the pit to enliven the senses.

Moses is the perfect role for John Tomlinson at this stage of his career as it involves no lyricism and precious little singing. Most of his text is declaimed in Sprechstimme, a half-sung/half-spoken way of articulating the words and notes, so the wear and tear on his voice which has blighted so many of his recent performances is used here almost as an advantage. As ever he’s a magnetic stage presence.

Rainer Trost gives a febrile, fervent performance which verges on the deranged as his brother Aron, whilst the supporting cast is without a weak link, each soloist grabbing their opportunity to shine.

But it’s the Chorus that is the true protagonist in this work, and the augmented Chorus of WNO delivers a blistering account of this impossibly difficult score. At full throttle they’re spine-tingling, but even their hushed incantations had a similar intensity whilst their acting was fully in keeping with the fervour required of them.

Lothar Koenings and the Orchestra of WNO deliver an impeccable reading of this work; their performance was nuanced, overpowering and played with pinpoint accuracy. It’s been a fantastic season at Covent Garden, and this visit from WNO is the icing on the cake. Unmissable.