In his production of Idomeneo for the Royal Opera, Martin Kušej presents the earliest of Mozart’s great operas as a study in the limits and illusions of regime change. “Utopias fade. Rebellions decay. The people remain,” proclaims the slogan projected on to the curtain at the end of the opera, when Marc Minkowski conducts a truncated version of the opera’s ballet music, before a series of tableaux on designer Annette Murschetz’s revolving set underlines the points that Kušej is making.

The Crete to which Idomeneo has returned after 10 years fighting the Trojan war has become a modern police state, controlled by the High Priest and his retinue of leather-jacketed, gun-toting thugs. Idamante’s decision to set free the shipwrecked Trojans is the spark that ignites the dry-tinder of rebellion – Idomeneo’s insistence on offering his son as a human sacrifice to Neptune is intended less as an act of propitiation here than an example to those who defy the regime, and the “sea monster” who ravages the land at the end of the second act is rendered as an outbreak of unprovoked violence by the regime against its people.

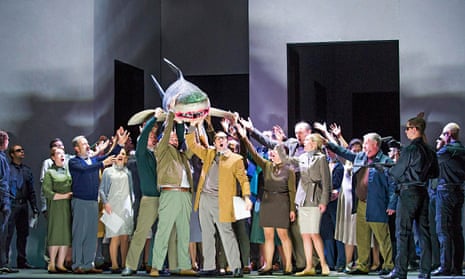

Some of the subsidiary details are thought-provoking, others just puzzling – why do the Cretans gather around a shark washed up on the beach? Why does Arbace carry around a piano accordion? What has the astrological sign of Pisces got to do with it all? But there’s no lightness about anything, just a deadening seriousness, with most of the dramatic life sucked out by the didacticism, and the protagonists only characterised in the most generalised way for what they represent rather than for who they are.

Musically it takes a good while to come alive as well. Minkowski reserves his most convincing, energised conducting for the ballet music, and much of what comes before it manages to be simultaneously precious and dull, with some particularly intrusive fortepiano continuo that’s distracting rather than decorative. The singing is decent if rarely exceptional. Matthew Polenzani is Idomeneo, secure in his arias but, thanks to the production, just a cipher on stage. Rather than the soprano or tenor we usually hear nowadays, Idamante is a counter-tenor, Franco Fagioli, who might have made the switch more convincing had at least a few of his words been intelligible. Sophie Bevan’s Ilia is another character circumscribed by the production, while Malin Byström is the cool but sexy Elettra. The best performance, despite the accordion and an eye-patch, comes from Stanislas de Barbeyrac as Arbace, singing his aria with sustained beauty of tone, and bringing real presence whenever he comes on stage. There’s too little of that elsewhere.