The Royal Opera’s latest attempt to connect with a wider audience takes it to the Roundhouse in north London, with its first ever staging of the earliest of all operatic masterpieces. The director, Michael Boyd, is making his operatic debut with Monteverdi’s Orfeo too; his production, designed by Tom Piper, updates the opera in a way that maintains connections with its historical and mythical roots yet allows the human dimension of the ending to pack a powerful punch.

Piper’s set reimagines the Mantuan court of the Gonzagas, for whom Monteverdi composed Orfeo in 1607, with the ruler and his consort (who are also Pluto and Proserpina in the fourth act) looking down on the circular performing space from a gallery. Orfeo, Euridice and their friends begin the first act in chains, casting them off for their wedding ceremony, while the shepherds of Monteverdi’s scenario are recast as priests, pastoralists becoming pastors, and there is the pervasive sense of the action taking place in a society in which religion has an oppressively controlling role. It is not Apollo who consigns Orfeo to the heavens in the final act but a priest, and the pain of his final, forced separation from Euridice provides the opera with a searing final image.

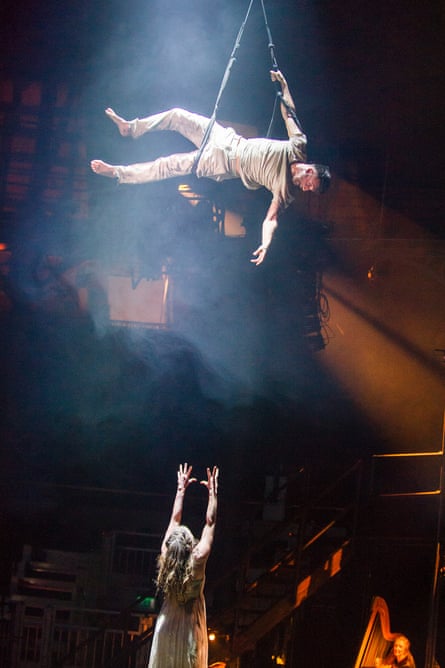

With the audience surrounding the action, and discreet amplification of the voices ensuring that every word of Don Paterson’s often striking English translation of the text comes across, there’s a tingling directness about the whole performance, which makes it compelling, especially from the third act onwards, beginning with Orfeo’s confrontation with Charon and his bouncer-like henchmen. Orfeo’s great aria at that point, Possente Spirto, is the opera’s climax, and it’s sung with mounting, almost desperate fervour by the baritone Gyula Orendt; everything human about the drama is suddenly engaged and from then on Boyd’s production never falters, and his theatrical ideas, such as the movement group (East London Dance) suggesting the swirling waters of the River Styx seem both beautifully simple and superbly effective.

The Guildhall School of Music and Drama supplies the chorus, and the orchestra is the Early Opera Company’s with a pungent continuo group of three lutes, harp and keyboard; the conductor Christopher Moulds ensures that this is always muscular, vivid Monteverdi playing and singing. There are no weak links among the soloists either; Susan Bickley combines the roles of Silvia and the Messenger, while Mary Bevan is both the touching Euridice and La Musica in the prologue, which she sings cradling the body of Orfeo in her arms, anticipating the end of the opera, when Orendt’s Orfeo holds the dead Euridice. It’s a typically neat, effective Boyd touch; the production really doesn’t get very much wrong.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion