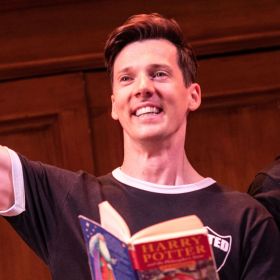

Sally-Anne Russell, Jeremy Kleeman and Emma Matthews; Photo by Jeff Busby.

The doctrine of the affections in music, visual arts and theatre was developed in the Baroque era and put simply, proposes that certain gestural and rhetorical characteristics can be associated with particular emotional responses. René Descartes proposed six basic affects: Admiration (admiration), Amour (love), Haine (hatred), Désir (Desire), Joie (joy) and Tristesse (sorrow), to which anger and jealously were added by others.

Unfortunately, throughout this exercise on Monday night the most defined emotions I experienced were anger, a strong sense of Tristesse and profound boredom. Beginning with the ensemble: instruments and bows were modern (played in a historically informed manner or ‘Vegetarian’ style as it is known in the trade) with an explanatory note in the printed program that this was because of the demands of touring and the variety of changing atmospheres. Baroque ensembles (and indeed far earlier) have been presented by Musica Viva over decades past and have managed the demands of touring with old, indeed, ancient instruments (next week in the Melbourne Recital Centre patrons have the opportunity to hear the specialist Baroque ensemble Concerto Italiano performing Monteverdi using such instruments on a tour to New Zealand, Melbourne and Perth). Modern high pitch and equal temperament were chosen, without explanation.

But more curious still was the involvement of the ARC Centre of Excellence History of Emotions in this project which provided an elaborate questionnaire after the performance for patrons to complete asking for their emotional responses, with questions such as ‘Music makes me want to jump up and down’, ‘It irritates me to be around angry people’, ‘I melt when the one I love holds me close’ (agree or disagree, from 1 to 5).

Please! The latter seemed to dress up the unsatisfactory under the banner of ‘research’. Surely this ‘research’ would need to take into account the fact that the instruments and pitch were not of the period. Similarly, by placing the instrumentalists upstage behind the soloists hindered the necessary rapport for affections to be realized. Finally, the prescribed, reduced orchestration by the late Alan Curtis and Calvin Bowman – the continuo section being reduced to cello and harpsichord – severely limited the expressive and emotional possibilities of improvising lutes and theorbo etc. For this was how Baroque opera was performed, with continuo in close proximity to and before the singers improvising with deep sensitivity and responsiveness to the theatre and drama taking place before them. Instrumentalist and singer could see each others’ eyes. Similar to jazz musicians realizing a chart; music led by words.

The three singers were each excellent artists with accolades going particularly to Sally-Anne Russell’s glinting, golden-toned mezzo and the young bass-baritone, Jeremy Kleeman, an agile and expressive actor who sometimes achieved real beauty of tone, though had a worrying constant vibrato in more excitable music. What was concerning was there appeared to be little governing musical discernment and consistency of ornamentation, with a wide range of styles, some glaringly inappropriate to the period. Singing notes as fast as possible and as outrageously high as possible with no regard for period style was a tiresome, wincing reminder of performance practices past.

Fine Baroque music is far more subtle and complex than putting together disparate components and hoping for the best: first, there needs to be an intelligent, imaginative, sensitive, firm, musical direction, intent and ‘voice’. Surely heard at its best, instruments need to be of the period, the instruments written for by the composer and in prescribed numbers. Next, the pitch and tuning temperament need to be appropriate for the period. Finally, the voices need to work sympathetically within this sound world rather than ‘doing what they do best’ at the front of the stage. Concerto vocale. And those building blocks established, the frills and ornaments can then be carefully worked on. Only then we can begin a discussion on the affections of music.

The libretto (unprinted) was difficult to evaluate, the prescribed musical arrangements were competent, though annoyingly unsatisfying, the set and costume designs were adequate (the rising luminous moon and Selena’s turquoise costume and tiara drew delight), the production was simple but effective (with, perhaps, a dozen too many ‘sustained drawn swords in outrage’) and the traditional lighting seemed elaborate, but clumsy.

I don’t believe that we made it to the moon on Monday night nor anywhere much higher than Southbank for that matter. This wonderful repertoire deserves far, far better.

Rating: 2 stars out of 5

Voyage to the Moon

Presented by Victorian Opera and Musica Viva

Melbourne Recital Centre

Monday, 15 February, 2016

Elisabeth Murdoch Hall

Phoebe Briggs (Musical Director and harpsichord)

Michael Gow, writer and Director

Alan Curtis and Calvin Bowman (Music Arrangers)

Christina Smith (Set and Costume Design, acknowledging the Sydney Costume Workshop)

Matt Scott (Lighting Designer)

Luke Hales (Production/Stage Manager)

Peter Darby (Head Electrician)

Phillipa Safey (Repetiteur)

Michelle Zarb (Musica Viva Operations Co-ordinator)

Emma Matthews (Orlando/Selina), soprano

Sally-Anne Russell (Astolfo), mezzo-soprano

Jeremy Kleeman (Magus), baritone

Emma Black, oboe

Rachael Beasley, violin

Zoë Black, violin

Simon Oswell, viola

Molly Kadarauch, cello

Kirsty McCahon, double bass

A collaboration between Victorian Opera and Musica Viva in association with the Performance Program of the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for the History of Emotions, Europe 1100-1800.