Blood, sand and tears: A foreign correspondent’s view of the opera ‘Fallujah’

LaMarcus Miller, foreground, Zeffin Quinn Hollis, left, and Ani Maldjian perform a scene from the opera “Fallujah” at the Army National Guard in Long Beach.

The Iraq war hunkered in the soul as the air filled with scents of gunpowder, burning tires and death.

Helicopters flecked the dusk as boys played soccer in the dirt and the pigeon men released their flocks against the setting sun. I craved that time even though I knew what night would bring. Radios squawking, American soldiers, their boots the color of sand, sweated in helmets beneath the stars. Insurgents moved like breezes through cities and villages. A clatter, a breath. Flashes broke the darkness and fallen bodies were hustled past wild dogs on the prowl.

The Long Beach Opera’s production of “Fallujah” is a trip into the torment endured by U.S. troops and Iraqi civilians. Performed at Long Beach’s Army National Guard armory, it captures with the vividness I recall as a correspondent and the anguish, rage and bewilderment of disparate cultures and lives trapped by larger designs. Told through the haunted mind of Lance Cpl. Philip Houston (LaMarcus Miller), the opera, composed by Tobin Stokes with a searing libretto by Heather Raffo, is the story of Iraqi and American mothers trying to save their sons from perilous fates.

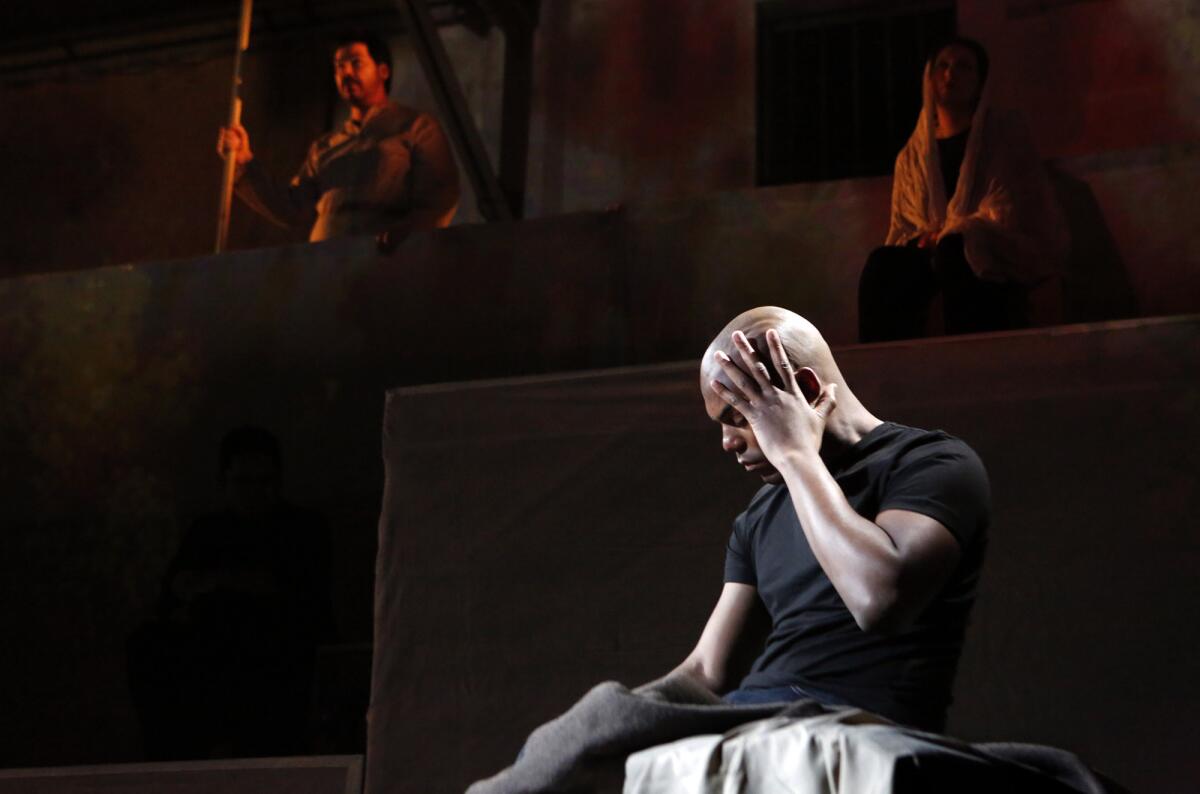

Clockwise from top, Zeffin Quinn Hollis, Ani Maldjian, LaMarcus Miller, Jason Switzer and Jonathan Lacayo perform a scene from the opera “Fallujah” at the Army National Guard in Long Beach.

The U.S. invaded Iraq in 2003 with the bluster of a superpower, but as the years went by the war for many Americans became an unfinished distraction that carried the whiff of failure. Much of that frustration unfolded in the desert city of Fallujah, an evocative namesake for an opera that ambitiously veers from combat to the seen and unseen scars it leaves behind. Unlike movies about Iraq and Afghanistan, such as “American Sniper” and “Lone Survivor,” “Fallujah” is scoured of jingoism and lays bare the suffering on both sides.

Rising along the banks of the Euphrates River, the city of Fallujah riveted the American consciousness in 2004 when four U.S. contractors were ambushed, their bodies hung like charred ornaments from a bridge. The grisly images were a sign that President Bush’s “Mission Accomplished” slogan was premature and that U.S. forces were slipping into one of America’s longest wars, a mesmerizing landscape of insurgents, jihadists, kidnappers, tribesmen and bomb-makers.

Fallujah was a visceral touchstone to American hubris and plans gone bad. With Baghdad to the east and the Syrian border to the west, the city appeared untamable, its defiance resounding across a sweltering territory known as the Sunni Triangle. After American troops withdrew from Iraq in 2011, Fallujah, whose history stretches to Babylonian times, was under nominal control of the Iraqi government until 2014 when the Islamic State swept through its streets.

An opera bearing such a name conjures a swirl of allusions even before the first note is struck, the first word uttered. The city has disfigured — physically and psychologically — a generation. It has trapped Iraqis in sectarian and extremist bloodletting and reminded Americans that the echoes of battle reverberate through the homes of veterans and the clinics that fit them with titanium limbs and treat them for post-traumatic stress.

“Can’t rest/can’t dim the lights,” sings Lalo (Gregorio Gonzalez), a senior lance corporal in desert fatigues. “Left a piece of myself there/can’t be anywhere but there.”

The voice is at once piercing and broken, as if a call from a Greek warrior across the centuries. It carries immediacy but is freighted in new wounds rising from ancient lessons not learned.

American soldiers took heavy casualties in Fallujah, and the city’s eventual succumbing to the Islamic State was regarded by many veterans as a failed mission and a sacrilege to comrades lost. About 4,500 U.S. soldiers were killed in Iraq; there has been talk in the presidential campaign of sending troops back to defeat militants.

But “Fallujah” echoes with the pain of the other side too. Hundreds of thousands of Iraqis have died since 2003, many of them civilians like the opera’s Shatha, a mother surrounded by brutality and worried for her son, Wissam. They represent the counterpoint to the American narrative; while U.S. soldiers raced through villages in Humvees beneath the glare of snipers, Iraqi families hid in the smoke and heat and tried to keep sane amid rolling battles and mortar rounds.

“Wissam, today my shoes were covered in bits of flesh,” Shatha sings. “Today I saw a death so terrifying, it tears you into pieces / your feet not where you were last standing / your hands not holding the hands of those you loved / And worst of all, it can spare you / and take your son instead.”

Watching “Fallujah” one is reminded of the misery and inscrutable fault lines across the Middle East. The Iraq war was followed by the false hopes that Arab uprisings in Syrian, Libya, Egypt and Yemen would lead to stability and a semblance of democracy. But extremists and intransigent Syrian President Bashar Assad filled the vacuum as refugees spilled across Europe and terrorist attacks led to fresh graves in Paris and San Bernardino.

The opera is also a testament to the scars of American soldiers, many of whom returned to a country that had grown weary of their mission and aloof to their suffering. When “Fallujah” opens, Cpl. Houston is on suicide watch in a veterans’ hospital. His shoes and belt have been taken. His mother waits outside. He plays and replays the things he witnessed and the blood he shed in a distant land.

“Can’t feel what’s wrong / can’t heal what’s gone,” he sings. “Wanna hurt / but nothing hurts / too dangerous to be alive / dangerous to be outside / where nothing hurts / find hurt / to stop me from going numb.”

Twitter: @JeffreyLAT

------------

‘Fallujah’ at Long Beach Opera

Where: Army National Guard, 854 E. 7th St., Long Beach.

When: 2:30 and 8 p.m. Saturday, 2:30 p.m. Sunday. Friday night’s performance was broadcast live on KCET and Link TV and may be viewed online at kcet.org/shows/fallujah.

Info: (562) 432-5934 or www.longbeachopera.org

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.