The famous portrait of Mussorgsky by the Russian painter Ilya Repin, currently on show at the National Portrait Gallery, tells you all. Bloodshot eyes, matted hair and beard, skin puffy and sallow, eyes distant yet wild: within days, Mussorgsky (1839-81) would be dead of drink, aged 42. He received no proper training in composition. Nor did he ever earn his living from music. Born into Russian nobility, he went into the army then spent his increasingly dissolute life as a government clerk, suffering alcohol-induced epilepsy, bouts of madness and destitution. The rumour that his grave is now under a bus stop is hard to verify but completes the sad picture.

Yet he had friends and admirers, most of them fellow composers. Many went to extreme lengths to support him. Rimsky-Korsakov – that great enabler and wizard of orchestration – and much later Shostakovich each had two attempts at making Mussorgsky’s only completed opera, Boris Godunov, “better”. He was working for the forestry department when he wrote this awkward, misshapen masterpiece based on Pushkin. It was rejected by St Petersburg’s Mariinsky theatre in part for its lack of a leading female role. The usual Boris we hear – to give a Snapchat version of the work’s protracted history – is the epic, expanded 1874 score. In a compelling new staging by Richard Jones, conducted by Antonio Pappano, the Royal Opera has dared – for the first time – to go back to the 1869 original, in all its rawness.

Mussorgsky’s orchestration, at once shining and murky, creates great blocks of chords, moving with unadorned, almost clumsy simplicity (exactly the characteristic of this composer which Rimsky was keen to polish and refine). You can see why he was misunderstood, music’s equivalent, perhaps, of his younger contemporary, Van Gogh in Starry Night mood. If you wondered what violas sound like, after hearing this score you need never do so again. They dominate the string writing, mellow and resonant, warmly played in an evening of excellence all round from the ROH orchestra. Pappano wrung every ounce of variety from the music, and entirely justified the use of the original, which ends so abruptly, without redemption, with Boris’s death.

The bass-baritone Bryn Terfel sings the title role for the first time. Whereas the later version places the emphasis equally on the suffering of the Russian people, here the action is truncated, bald, almost static. The tsar’s torment drives the piece. Terfel must carry the drama, which he does, superbly. Once anointed tsar, with a triumphant chorus and clamour of bells, Boris does little except brood and stare at a king-sized map of sprawling, unruly Russia. He is a good and honourable leader but is stained by his part in the murder of the young tsarevich Dmitry, which enabled him to take the crown. The dilemma of power and the dark path that led to it haunt him.

Plague and famine appear to prove Boris’s guilt, and leave the people – here an enlarged and excellent chorus of peasants in all versions of subfusc – starving and rebellious. Mussorgsky may have used rough tools when it came to orchestration, but he knew what he wanted from his voices, giving detailed indications on phrasing and dynamics. In his vital “hallucination” scene, as Boris grows deranged, Terfel sings with a ghostly lightness, as if his great, golden voice had been reduced to a sickly pallor. The effect is terrible and terrific. In Terfel we have a powerful new Boris, sure to turn out more reliable and enduring than the historic character he portrays. He was joined by a top ensemble cast, with John Tomlinson, once himself the ROH Boris of choice, a popular presence as the drunken monk Varlaam, John Graham-Hall insinuating and snakish as Shuisky, Ain Anger a towering Pimen and Ben Knight clear and touching as the young Fyodor. Two ex-Jette Parker young artists, Kostas Smoriginas and David Butt Philip, deserve praise.

Richard Jones has found a fresh approach to a work locked deep in its Kremlin past. Miriam Buether’s set, a black box embossed with bells and hung with icons, serves as monastery, state room, inn and public square. In a vaulted room above, a dumbshow of the assassination of the young tsarevich is re-enacted, over and over. Nicky Gillibrand’s costumes splice ancient with modern. The coronation scene, with its splashes of bright colour and toy-town cardboard crowns, elicits unexpected grandeur. Lit by Mimi Jordan Sherin, the whole looks handsome. Someone will no doubt explain to me why the boyars were dressed like ushers from 1950s cinemas. It may be a boyar fashion detail that’s passed me by. Try the live screening tomorrow. Then go to the real thing.

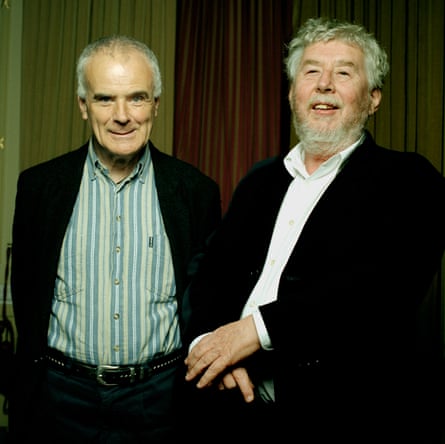

Many generous tributes have been paid to the composer Peter Maxwell Davies, who died last Monday, aged 81. Max has been part of our musical landscape since the late 1960s, first in the Pierrot Players, which became the Fires of London, eventually and unpredictably becoming master of the Queen’s music. His friendship with Harrison Birtwistle, from their Manchester student years in the 50s, helped shape the identity of both young Lancastrians. Later they drifted apart. Last week, I spoke to Birtwistle, who remembered Max warmly, recalling how much he learned from him in those early days, and speaking of their many shared interests, including medieval music, misericords and an abiding, salty sense of humour. Birtwistle said of his death: “The bugger beat me to it.” Max would have chuckled wickedly.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion