Florentine’s ‘Sister Carrie’ Is a Triumph

World premiere boasts strong score, great cast, uneven drama.

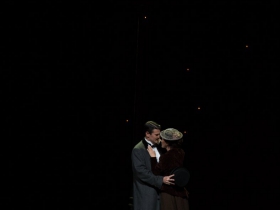

Sister Carrie at the Florentine Opera. Scenic design by Kris Stone, lighting design by Noele Stollmack, costume design by Rachel Laritz , wigs and makeup by Dawn Rivard. Photo by Kathy Wittman

Magnificently sung and acted by its two leads, the world premiere of Sister Carrie was presented by the Florentine Opera on Oct. 7 and 9. It was simultaneously recorded live for the Naxos classical label, meaning the larger global public can soon enjoy it and needn’t rely on reviews by the show’s critics.

Except for not seeing the visual staging elements, the public can decide for itself where to place Robert Aldridge’s music and Herschel Garfein’s libretto among the new operas aimed at the highest echelon of the international repertoire.

Even though we often demand more of the new repertoire that we did of the old, I place the opera high for the dramatic elements as well as its virtuoso demands on the human voice. It is not at the apex – the first act is better than the second — but certainly among the top efforts to revitalize and deepen Americana themes and musical syntax.

This is not an opera that can be judged entirely on the size of the voices and the opportunities to show them off, though those are considerable. It is hard to imagine a better Carrie than mezzo Adriana Zabala nor an improvement to baritone Keith Phares as her imploding lover, George Hurstwood. It is even harder to imagine a score that could more successfully demand acting of such subtlety and singing power.

The staging is essential to master the broad expanse of Uihlein Hall in the Marcus Center for the Performing Arts. It also must reflect the constant motion and contradictions of urban America that dominate the original Theodore Dreiser novel, published at the turn of the 19th century into the 20th. Though students are still ordered to read Sister Carrie in college, many opt for the CliffsNotes. The detailed naturalism, the step by step pattern in the highs and lows of urban society plus the author’s refusal to pass judgment on “fallen women,” was a style ahead of its Victorian time that has over a century sadly fallen out of favor.

Fortunately, Aldridge and Garfein are intense and loving readers who also recognized how those times and this tale are stirringly relevant to modern conflicts – and could be enhanced by the spectacle elements of opera.

The music and words become a symbolic marriage with Dreiser’s original, elevating its naturalism into operatic form.

Aldridge understands the era while ranging across his own opera signatures (as anyone who recalls the same team’s Elmer Gantry will realize). In tonality it is close to the period yet deliberately fresh in unexpected extension of notes and adventurous inversions on the way out the door. The compositional arias are not “stand on your hind legs and sing out,” but intricate pacing within the behavior.

The overture establishes a metallic crash and surge of brass and percussion struggling against lyrical movements and unresolved romantic conclusions.

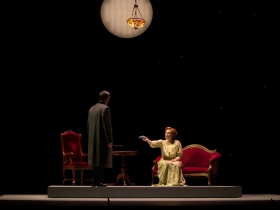

It is a constant clash. The characters may be drawn into the big city allure of wealth and celebrity, yet are left strangely empty, isolated by the spotlight progression and dark pools provided by lighting designer Noele Stollmack.

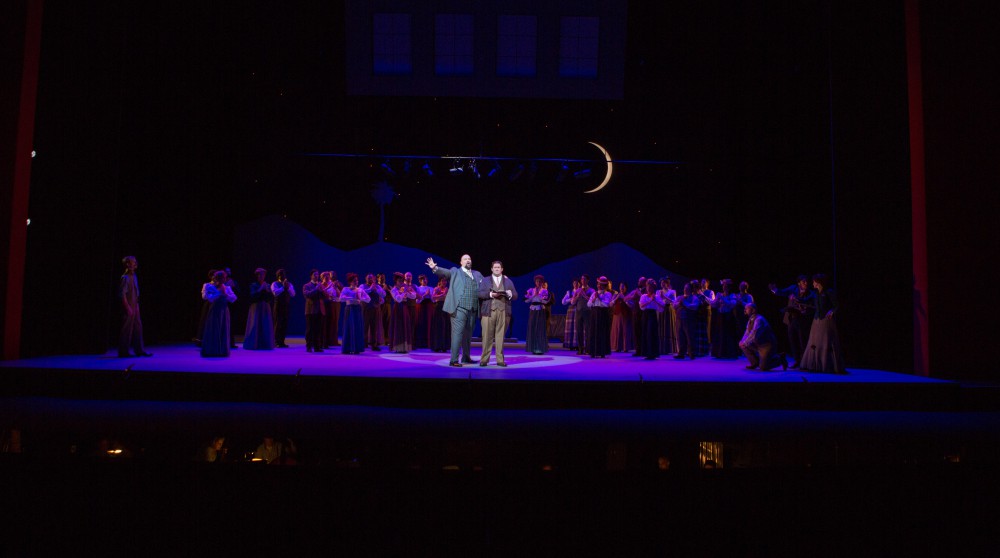

Scenic designer Kris Stone continues the metaphorical clash. While most of the action takes place on platforms rolled onto the stage, and less successfully with theater lights and other droppings from the ceiling, behind it all looms an enormous rail bed of toothed wheels and gears. The gears symbolically mesh the shoe factory floor, the train station, the lonely streets, the nightclubs, the mechanically surging mobs — the entire urban hub that draws Carrie in from Wisconsin and spits her out into ever advancing entanglements. Like Dreiser, the opera never judges or looks away. But it does land some pointed suggestions.

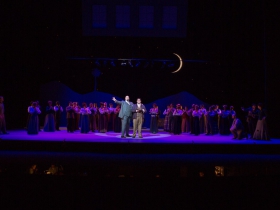

Given all these rolled-on locales, the stage cannot constantly drip with trappings of jewels and similar wealth – though costume designer Rachel Laritz certainly can when permitted elegance. So the music and lyrics provide. They raise the nightclub dining and five-course meals into arias and chorales. Then at the other social extreme are the homeless wandering Times Square. Just as Dreiser was unflinching in his portraits of the times, so has librettist Garfein extended the trivialities of good eating, or the mechanics of a female assembly line, or angry men huddling and cursing on the street into major musical numbers.

It’s a little jarring at times – the assembly line in particular is too long, as if a clip from Modern Times was stuck in the projector. But the method later has winning moments. Everyday words are given an amplified and meaningful repetition — a musical opportunity Aldridge seizes.

Stage director William Florescu has to manage a complex flow of scenes and people – including the large Florentine chorus. The production is almost too busy in the second act, but Florescu recognizes that the opera rides on the strength of his lead performers. They have an empathetic connection to us, even when apart in contrasting scenes. The director strives not to let the complications of the plot interfere with this emotional bond, but eventually calls in too many big guns of stage drops and panel manipulations.

Our eye always seeks out the center – the doomed Hurstwood and especially Carrie. The warm tenor of Matt Morgan as Drouet introduces this unhappy factory worker to a seductive world, though Morgan’s carrying power is notably less than the two leads. He disappears from the story soon after smoothly leading Carrie into corruption (a sequence involving some of Garfein’s neatest repetition of lyrics).

From kept woman to sought woman to pursued woman to pretend new bride to Broadway star, Carrie is carried along by the desires of men in a man’s world — until she stands alone and even aloof in her success.

The parallel story is the melting of a man of means and proper family into a thief, a braggart, a homeless derelict and striker scab, with a garret gas pipe waiting at the end. As Hurstwood falls, Carrie climbs, never losing her central appeal and curious form of innocence, even while growing in her cynical self-sustainment.

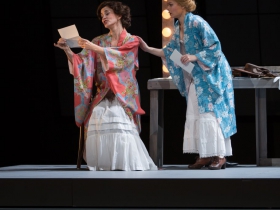

The music creates remarkable room for a singer to elongate a “yes” or hurl accusations. Zabala’s posture becomes an acting element, conveying allure, demands, humor — whatever role Carrie has molded herself into.

Opposing musical moments pinpoint her transformation — her “everything is paid for” wonderment as she is introduced into higher standards of living, then her determined decision at the end that, however untrustworthy, “money is everything” and all one can expect from this world.

Despite what patrons are seeing and hearing about Carrie, they remain as enchanted as the Broadway johnnies and rich men who have shaped her life

Phares as Hurstwood has the reverse – a descent but an equally difficult and riveting acting-singing challenge. He moves from the confident baritone booming his power at a posh Chicago eatery to a slovenly layabout boasting he’s still an important man of the world (a wonderful aria/soliloquy).

The roles require elaborate singing throughout their ranges, vocal passions turning dispassionate. The first act ends in a haunting unusual duet on a train forecasting emptiness down the track.

At first Manhattan provides an inviting nightclub party to introduce the couple, including a welcoming giddy soprano sequence for powerful Ariana Douglas. It’s a second act that gets looser, not more focused in character progression – almost as if Aldridge and Garfein felt compelled to add the more traditional demands of opera and play excessively with the large chorus and most amusing words (which appear above the stage in supertitles, largely unneeded but occasionally different than the words being sung onstage).

For anyone who might long for the bel canto trills of classical opera, these are provided in rapid abundance during a backstage “mash notes” duet by Zabala and fine soprano Alisa Suzanne Jordheim as fellow chorine Lola.

To detail Carrie’s advance in theater there’s a mock Arabian nights tale with ditties much as if Sigmund Romberg’s The Desert Song was being interrupted by flippant counterpoints from modern music.

Similarly a defiant march – another light dash of Romberg but flipped in meter and purpose — rises among the homeless, the strikers and the strikebreakers. In coarse angry words it is a persistent blunt reminder that the common man was paying quite a price as Carrie rises. It becomes another clashing theme against Carrie’s music hall ascendance and Hurstwood’s fall.

When circling hordes and picket signs flood onto the stage their complex interweaving of musical lines is not as clearly sung as should be by the chorale or its soloists. Here, too, the accomplished orchestra – much of the Milwaukee Symphony under conductor William Boggs’ otherwise impeccable care — adds to the imbalance.

But the intended purpose is crystallized in the finale. Carrie and her chorus girls stand under her name in lights on one side of the stage as Hurstwood recedes into darkness on the other side. The bitterness of the march echoes from the rafters as the orchestra combines clangs and crashes with a sweet, sad and dangling musical line.