What am I supposed to do with myself now that it’s over?

That was my immediate thought as I stumbled out of the State Theatre at the conclusion of my first ever Ring Cycle, clutching an archival print of the original Bayreuth scenic design backdrop I had bought at the Ring Cycle pop-up shop.

When Opera Australia and Neil Armfield’s Der Ring Des Nibelungen first premiered in Melbourne in 2013, I had just returned from two years overseas seeking fortune and inspiration – bringing back much of the latter and a severe deficit of the former. My mother and I, poor as church mice, crowded around a tiny radio in her forest cottage and listened, enthralled, as ABC Classic FM broadcast the entire cycle: Das Rheingold, Die Walküre, Siegfried and Götterdämmerung – four operas which amount to around 16 hours of music in all.

Summarising the story of Wagner’s epic takes some doing – though it may remind the casual reader of that other famous tale of a magical ring. It begins in prelude, when the scheming dwarf Alberich denounces love in order to steal the precious “Rheingold” – a treasure that can be forged into a ring of great power – from its guardians, the Rhinemaidens. The gods, led by Wotan, are struggling to repay the giants Fasolt and Fafner for building their godly castle, Valhalla.

Word gets out about the existence of the ring, and the fate of the gods – and humankind – is set in motion.

Throughout the coverage of that earlier production, I saw a few photos of Armfield’s interpretation – particularly the rainbow bridge that closes Das Rheingold – and was sad that I wouldn’t get to see such a magnificent staging in real life. So, when Opera Australia announced a return season in 2016, it was one of a handful of “dreams come true” moments in my life (the other being when Steven Spielberg replied to my fan letter in 1994).

Many present at the opening night of the revival had witnessed the 2013 production as well, and seemed more muted in their excitement than I. But as the lights dimmed before Das Rheingold, and maestro Pietari Inkinen emerged, a woman near me instructed her friend: “Listen for the first sound.”

I have never heard a theatre so silent in anticipation.

And then, there it was: 136 bars in E flat major, a drone set to create the universe before us. Buoyed by Wagner’s Vorspiel (prelude), Armfield’s vision of the waters of the Rhine as represented by hundreds of lazy bathers – like a lost, full colour Max Dupain photograph come to life – was almost overwhelming.

When the Rheingold appeared as bunches of bright golden tinsel rustled above the bathers’ heads, it was as though Armfield had returned us all to the Christmas mornings of our childhood.

Whether or not one “bought” this opening – with the Rhinemaidens in seafoam sparkles, like Tivoli Lovelies en route from a beachfront spectacular – seemed to set the tone for one’s reaction to the rest of the Cycle’s staging, which is contemporary – if not occasionally experimental.

In collaboration with set designer Robert Cousins, costume designer Alice Babidge and lighting designer Damien Cooper, Armfield favours a “poor theatre” approach (a performance style that focuses on the actor’s voice and body rather than theatrical excess). Nowhere is this more compelling than in the “black box” presentation of Die Walküre’s third act, the bare stage amplifying the magnitude of both father and daughter’s sorrow, as Wotan kisses Brünnhilde’s eyes with sleep. This approach also makes this Ring’s occasional moments of spectacle all the more arresting.

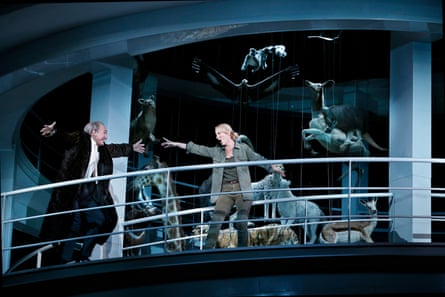

In Das Rheingold, the giants Fasolt and Fafner tear through a replica of the original Bayreuth backdrop in twin cherry-pickers, like brutish property developers; in Die Walküre, Wotan, Fricka and Brünnhilde spar upon a Jeffrey Smart-esque spiral exit ramp filled with suspended taxidermied animals; and in Siegfried, a lightbulb-ringed false proscenium with a blazing gold curtain represents the flames that separates the eponymous hero from the sleeping Brünnhilde.

And of course there’s that rainbow bridge: a stairway to the heavens populated with dancers reverently waving feathered fans in every colour of the rainbow as they usher the gods to Valhalla. It is mirrored in Götterdämmerung’s final image, as humanity gathers upon the steps to watch as Siegfried and Brünnhilde’s funeral pyre, built upon a carpet of cheap bouquets like those laid after the Lindt siege, ushers in the fall of the gods.

Given global political developments during the intervening years since the first presentation of this production and now, Armfield’s interpretation of Wagner’s cautionary tale about the pursuit of wealth and power feels even more urgent. For much of this we have the cast to thank – many of them new to the production.

Lise Lindstrom’s Brünnhilde, her first full Cycle in the role, should install her as one of the greats. Her tears at the standing ovation of her Götterdämmerung curtain call suggested a mix of relief and surprise at having conquered one of opera’s most punishing challenges.

James Johnston, compelling but lacking in power throughout Das Rheingold and Die Walkure, emerged in heartbreaking full voice as Wotan became the Wanderer in Siegfried. And as the doomed twin lovers, Bradley Daley and Amber Wagner are revelatory.

Returning as Siegfried, Stefan Vinke makes the headstrong man-child – a difficult role, and often one that can make Brünnhilde’s love of him seem baffling – more innocent than infantile. (His attempt to converse with the Woodbird, a spritely Julie Lea Goodwin, is delightful.)

Even though I was well aware of Siegfried and Brünnhilde’s fate, through Vinke and Lindstrom’s raw, generous expressions of their love I found myself clinging to the same false hope that a great performance of Romeo and Juliet stirs in me: maybe this time it will be different! Maybe the magic potions and disguises and interferences will all just be a big misunderstanding!

They are supported by an ensemble so towering in its talent that listing individual highlights becomes a Wagnerian task in and of itself. It is an expertly cast collection of performers, among them some of the country’s finest “singing actors”, that further deepens the vision that Armfield first laid out three years ago.

Though not a Wagnerian by any stretch of the imagination, I already appreciated the music of Der Ring before I saw it, but was unprepared for the magnitude of its live power. To watch the entire cycle, presented in the manner Wagner intended (complete with dinner breaks), is to go on a mammoth journey with the people around you. You don’t just experience a Ring Cycle, you survive it.

Under Inkinen’s watch, the Melbourne Ring Orchestra is in superb form, in particular the lower brass that is the Ring’s thrilling engine (and shout out once more to the Ring feature that so delighted me back in 2013, the “anvil orchestra”: an offstage room full of, well, playable “anvils” that soundtrack Das Rheingold’s descent into Nibelheim).

I was also reminded what it was like to watch something beautiful that you can never see again except in memory. We have become so used to accessing what we want when we want it – the movie you enjoy will end up on a streaming service; the concert or play will be filmed and released on DVD – that true one-offs are rare.

One of the great sorrows of any Ring Cycle is that the ticket prices typically reflect the monumental undertaking of the production. (A considerable irony, given the anticapitalist themes Wagner presents.) Could there ever be an egalitarian Ring Cycle, one that exists outside of profit margins and presents this godly masterpiece for the mortals? Perhaps one day, though the recent news that an anonymous donor had subsidised the remaining C-reserve seats for this Ring, halving the price, was thrilling; now that’s what I call philanthropy!

As for this former Ring virgin: over the past week the coupling of Wagner’s music with Armfield’s vision have inspired, thrilled and saddened me all at once. It’s easy to see how a “Ring-nut” is born.

Before the lights dimmed to herald Das Rheingold, a lady two seats away from me leaned across, her seatmate having told her this was my first Ring Cycle. “How wonderful,” she said, nodding solemnly. “This is an adventure that will last the rest of your lifetime.”

Sixteen hours later, I hope she’s right.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion