The chance collision of budget day and International Women’s Day last Wednesday was a satirist’s dream. What merciless fun WS Gilbert, the writing half of the Gilbert and Sullivan operetta duo, would have had. A sly dig at Essex boy Philip Hammond here, a savage swipe at collagen injections there. The text of Patience, English Touring Opera’s choice for their first ever G&S, does half the job already. There’s a joke about taxes in the opening dialogue (“The love of maidens is, to him, as interesting as the taxes… Would that it were! He pays his taxes!”). And the ageing Lady Jane, who must be all of 39, has an entire terrible aria bemoaning the ravages of time on her wrinkled body. A verbal shot of Botox and she’d have been laughing. So might we.

The sixth G&S collaboration, premiered in 1881, aims its darts at the aesthetic movement of the 1870s. Dandyism and self-obsession, personified by Swinburne, Whistler and Wilde, rule. Maidens are lovesick, sighing over the poet Bunthorne – he who pays his taxes – who is floppy of hair, hat, lyric skills and more besides. The score has lovely things but the work is insubstantial, and clogged with dialogue.

Told straight and in aspic, as ETO and director Liam Steel do here, Patience loses any vestige of contemporary currency. Florence de Maré’s sets, super-sized acanthus leaves a la William Morris, look pretty but give too little information or context. Dismantling and reassembling the piece with top comic script writers might have rescued it. You could make play, for example, of our current obsession with celebrity. Or just turn Gilbert’s misogyny on its head and cast it cross gender. Alas, all was left respectfully intact, with some ill-coordinated movement and somewhat clumsy acting. Iolanthe, with its lampooning of the House of Lords, might have been a better bet.

Musically there was plenty to enjoy. Timothy Burke conducted a nimble performance, with clean orchestral playing and engaging singing, from Lauren Zolezzi sweet-voiced in the title role, Bradley Travis, elastic-limbed and agile-voiced as creepy Bunthorne, and Ross Ramgobin, stiff and stuffy as his rival in dactyls and spondees, Archibald. Andrew Slater, Valerie Reid, Aled Hall and the rest of the ensemble entered the spirit as far as that spirit was identifiable. G&S fans – I can be one too; from-the-cradle credentials available on request – will find nothing to offend and the tunes will stick in your brain for weeks. Sing boo to you, pooh pooh to you. It’s now on tour until 3 June.

The Pirates of Penzance, a stronger piece, is back at the Coliseum in a revival of Mike Leigh’s staging. The improvement on first time round is considerable. G&S works, mysteriously, when you sense a company endeavour, with stars and chorus working together to make comedy out of the mix of situational idiocy and musical ingenuity. Gareth Jones conducted. ENO chorus and orchestra were on fizzing form at the Saturday matinee I attended. Movement was well drilled. Soraya Mafi’s sparkling Mabel, David Webb’s puppy-fresh Frederic, Ashley Riches’s shimmying Pirate King and Lucy Schaufer’s gloriously wearisome Ruth radiated collective humour. John Tomlinson, luxury casting indeed as Sergeant of Police, helmet askew, poured all the combined angst of Hans Sachs, Gurnemanz and Wotan into “A policeman’s lot is not a happy one”.

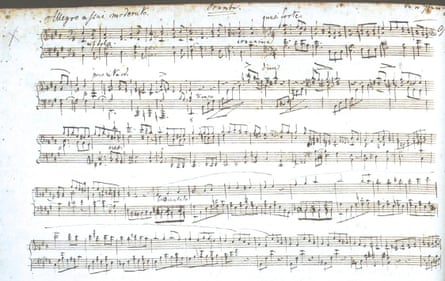

International Women’s Day occupied the rest of the week. Radio 3 dedicated all of Wednesday to music composed by women. It was a noble endeavour. They shouldn’t have had to do it. We understand why they did. Once, to redress the balance of decades, is enough. Now they must adjust their programming accordingly and stop referring to “forgotten women composers” unless they insert “by us”. The day’s highlight was a belated premiere of a piano sonata by Fanny Mendelssohn, once assumed to be by her brother, Felix Mendelssohn. Broadcast live from the Royal College of Music in a performance by the pianist Sofya Gulyak, the Easter Sonata is challenging and grand in scale. It may have the familiar hallmarks of romantic piano music, but the quivers and gleams of a richly individual talent shine through.

The London Oriana Choir has an excellent track record in not forgetting the forgotten. Women’s music has long been central to their concert-making. Their latest venture, five15, is to commission 15 works by five women composers, over five years. On Tuesday at St Martin-in-the-Fields, they gave the world premiere of Cheryl Frances-Hoad’s joyful and rampant The Food of Love – settings of texts by Christina Rossetti and Jonathan Swift – celebrating onions, oysters, melons, plums and other gourmand delights. It was an earthy prelude to an accomplished performance of Monteverdi’s Vespers of 1610, conducted by Dominic Peckham.

Finally a burst of praise for Helen Grime’s Piano Concerto, an enticing chamber work given its premiere by Birmingham Contemporary Music Group conducted by Oliver Knussen. Grime’s fellow composer, Huw Watkins – AKA Mr Grime – was the perceptive soloist. In this gleaming, meticulous work, soloist and ensemble were in sparky dialogue not combat. Life has moved on from the era of Clara and Robert Schumann – husband and wife – or Felix and Fanny Mendelssohn, siblings. Here, gender equality was freely at play.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion