An Enigmatic Evening at The Opera

John Daszak (Alviano), Catherine Naglestad (Carlotta), Christopher Maltman (Tamare), Tomasz Konieczny (Adorno), Alastair Miles (Nardi). Krzysztof Warlikowski, director. Ingo Metzmacher, conductor. Bayerisches Staatsorchester. Nationaltheater, Munich. July 6.

MUNICH — One of the most intriguing events at the 2017 Munich Opera Festival has been the programming of Die Frau ohne Schatten and Die Gezeichneten, both directed by Krzysztof Warlikowski on consecutive evenings at the Nationaltheater. While the Strauss opera is a connoisseur’s piece, it has a firm hold on the standard repertoire; the Schreker, on the other hand, remains little known. That said, Die Gezeichneten is undergoing a renaissance of sorts: Nikolaus Lehnhoff’s 2005 production for Salzburg conducted by Kent Nagano started it all, helped by a commercial DVD release. It had its American premiere at the Los Angeles Opera five years later, followed by productions in Palermo and Lyon. Now we have this lavish production in Munich, with productions in Köln and Berlin beckoning.

Why the sudden interest? 2018 being the centennial of the work’s premiere may have something to do with it. Die Gezeichneten (1911–18) coincides almost perfectly with Die Frau ohne Schatten (1911–15). Both operas are heavy on symbolism and the subconscious—Freud and Expressionism were all the rage then. Both Strauss and Schreker composed in the post-romantic style, with Strauss the more “progressive” one, employing expanded tonalities and a more advanced harmonic language. Hearing these two pieces on consecutive nights—especially under the same stage director—was a fascinating musical and dramatic experience.

Musically Die Frau holds our interest better, building to an impressive climax over three acts. It contains some of the most sublime melodies ever penned by Strauss, supported by a greater variety of tone colours and orchestral textures. The libretto is stronger, with what one would call a kernel of truth in the story—a dramatic crux of the matter that makes one care about the characters one sees on stage. In Schreker, I’m sorry to say, none of the principal characters are likeable, except perhaps Carlotta. This is basically a story of decadence and dissolution, of corruption and deceit. And when it is as provocatively-staged as this production by Warlikowski, it has the capacity to shock. To gain our empathy? I don’t think so.

For those unfamiliar with the opera, here’s a drastically simplified plot. Set in 16th-century Genoa, the nobleman Alviano Salvago is a deformed hunchback who dares not dream of love from a woman. He sublimates his sexuality into building Elysium, a beautiful island paradise for the people of Genoa. Unbeknownst to him, his fellow noblemen friends have been using an underground grotto on Elysium for nefarious sexual purposes with the young women they have abducted. Count Tamare, chief among the villains, has designs on the virtuous painter, Carlotta, who wants to paint the deformed Alviano—she’s interested in “painting his soul.” She rejects Tamare, who swears revenge. Meanwhile, in the painting session, Alviano admits that he cannot suppress his desire for Carlotta, who also confesses her love, although it’s not clear if it is physical or spiritual love. In any case it’s not consummated. The people of Genoa go to the island for the first time, and Carlotta wanders off into the grotto. Alviano goes into the grotto looking for her, only to find her having succumbed to Tamare’s advances. Alviano stabs Tamare and rushes to Carlotta’s bedside while she dies.

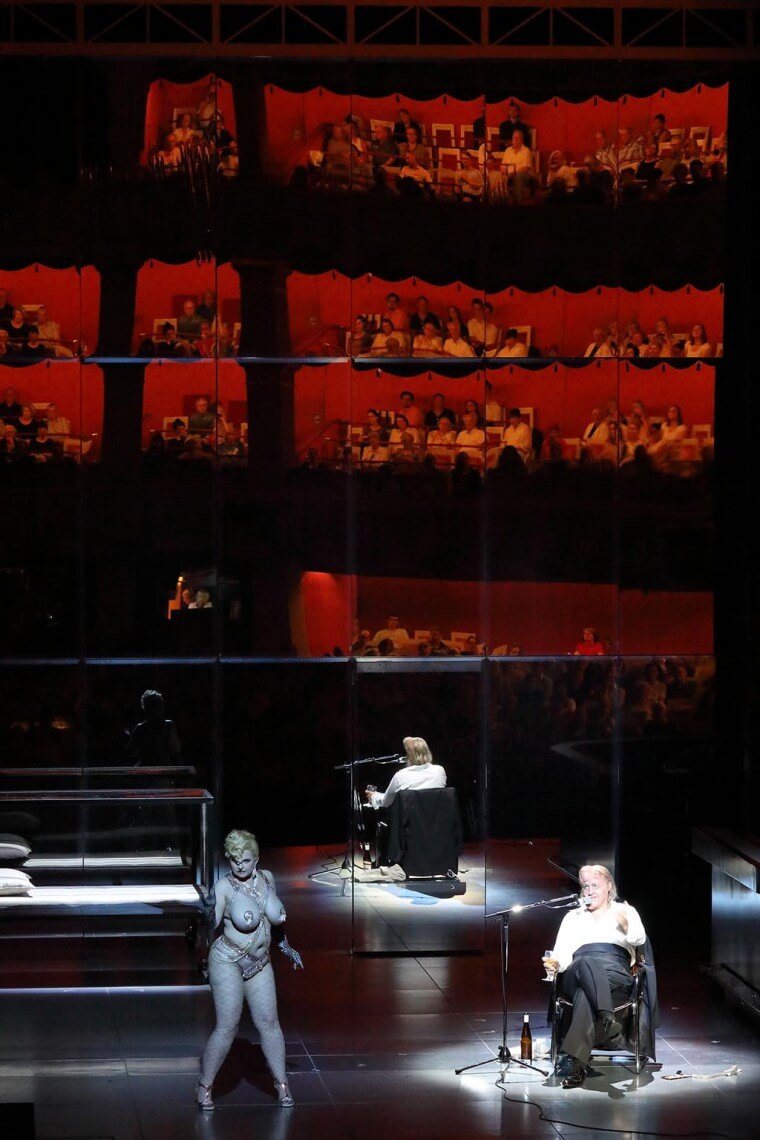

There’s an unrelenting dark core to this piece, and Warlikowski rightly takes aim at revealing its hidden (or not so hidden) darkness and irony. The central theme is of the struggle between beauty and purity (as represented by the paradise of Elysium), and the ugliness and corruption just below the surface, with all the sordid goings-on in this supposed paradise. However, the way Warlikowski chooses to express this darkness is sometimes bewildering: there’s a boxing ring on stage; a corpulent belly dancer gyrating downstage for a good fifteen minutes; ballet dancers en pointe, with half of them men and the women topless; the chorus wears rat heads à la Bayreuth Lohengrin; and there are screenings of silent film footages featuring Frankenstein, Nosferatu, and Phantom of the Opera.

Perhaps the most revealing (and audacious) moment is the monologue delivered by Alviano before the music starts in Act 3: a self-description written by Schreker, calling himself an Impressionist, Expressionist, Erotomaniac, and a Creator of Sound, among other juicy titles. Thank goodness for the English surtitles! Warlikowski is equating the character of Alviano with Schreker himself, an interesting take. I must say overall the dramaturgy leaves me a bit cold, as I find myself distracted from the music, which it’s not supposed to do. The vision of the stage director is meant to be communicated to the audience as fully as possible. But when the director’s vision is so convoluted and cryptic, its power is diminished and the message is lost, without a whole lot of tortuous and laborious explanations. In an ideal world, the audience should sense what the director is driving at instinctively. Given that we are in an age of Regie-driven opera productions, it’s unlikely to change soon.

Musically, Die Gezeichneten is a mix of late and post Romantic styles, accessible and quite appealing with its lush orchestration and sometimes transparent, other times sinuous tone colours. But it does tend to drift along a bit, without sufficient musical development to hold one’s interest for a whole evening, and it’s not exactly a short opera! Conductor Ingo Metzmacher gave a masterful reading of the score, bringing out extraordinary sonorities when called for. The singing was great, particularly John Daszak in the long and punishing role of Alviano. Also outstanding were baritone Christopher Maltman as Tamare and Catherine Naglestad as Carlotta. Baritone Tomasz Konieczny was equally fine as Adorno. The soloists were warmly applauded. I understand there was booing for the director on opening night. But on July 6th, with Warlikowski not present on stage for the curtain calls, there were only cheers.

For more REVIEWS, click HERE.

#LUDWIGVAN

- SCRUTINY | Opera Atelier’s All Is Love Makes Triumphal Return - April 15, 2024

- SCRUTINY | From The Heart: Ema Nikolovska And Charles Richard-Hamelin Offer Unique Program At Koerner Hall - March 26, 2024

- SCRUTINY | The Glenn Gould School Spring Opera Presents A Superb Dialogues Des Carmélites - March 22, 2024