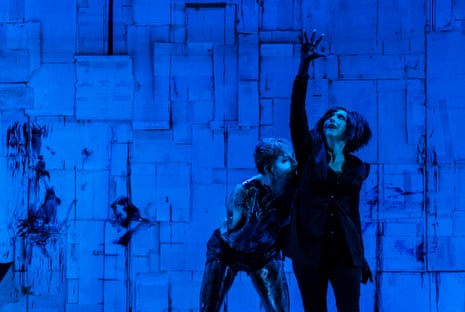

It’s a helluva thing to be born to play the devil … but there’s the cabaret star Meow Meow, all fingers, black and spindly limbs and hair, owning her every evil second she’s on stage in The Black Rider – the moral little opera created by William S Burroughs and Tom Waits.

Satan purrs as she sings; known as “Pegleg” in the text, she still manages to creep as she limps in thick black heels. She feeds silver bullets to the hapless hero even as she nibbles at his soul.

“You can’t cheat an honest man,” warns the devil. But who would want to stay honest when temptation appears at the crossroads in the form of Meow, sharp in shoulder pads and flawless comic timing?

She’s the best thing among many good things in Matt Lutton’s production of Burroughs and Waits’ “musical fable”, itself based on the German romantic opera Der Freischütz. Originally created by the Beat writer Burroughs and the musician Waits, with the theatre auteur Robert Wilson in 1990, a production of their collaboration first visited Australia for the Sydney festival in 2005.

But Lutton’s is his own take on the work, with an original design, musical direction from the excellent Iain Grandage and a cast drawn from opera, theatre and cabaret.

The story follows a bookkeeper who falls in love with a forester’s daughter. The father will not allow her to marry this man who cannot hunt, so the bookkeeper takes to the forest to teach himself to do so.

Here he meets Pegleg, who offers him magic bullets that will always find their target; the first supply, she makes clear, is always free. Soon, the bookkeeper is wading through the blood of his kills, demanding more bullets. These ones, of course, come at a cost; Pegleg will provide him seven bullets – six for him, but one for the devil to direct. Tragedy ensues.

The metaphors read from Waits and Burroughs rendering of the story is usually one of addiction. Burroughs’ own drug-addled violent history – he killed his wife in a drunken game of “William Tell” – is a match for the The Black Rider’s allegory of desperate acts, irreversible loss and consequence.

Wilson’s original production drew heavily on German expressionism: distorted angles and bold colours in the design, with faces blurred by facepaint – a reflection of the internal melodramas of a distorted mind. Lutton retains an expressionist frame but, whether deliberate or accidental, the contrast in the performances of the stage veteran Richard Piper as the father and the opera singer and Kanen Breen as the tragic hero offer a feminist reading of the story. Piper’s articulate, authoritarian insistence that the sweetly singing Breen adopt a masculinity defined by its capacity for violence is the act that destroys the hero’s soul and the father’s family.

Theirs are two excellent performances among a cast who manage to contribute consistently good ones without ever seeming to be entirely within the same show.

Perhaps it’s the variety of performance styles, but while Paul Capsis sings like an angel, the duet of the The Briar and the Rose between the lovers is exquisite, and Piper nails his every word, the unevenness disconnects the performers from the audience – a sensation enhanced further by Lutton’s stark, stilted stylisations of movement, of gesture, of design.

It looks beautiful, but it feels cold – like a diorama performed behind the glass door of a cabinet. Such would be in keeping with Lutton’s long-demonstrated preference for macabre, minimalist aesthetics but, while unleashing Meow Meow in full cabaret conversation with the crowd, it seems a waste to restrict Capsis.

Unevenness aside, it’s a show worth seeing. Fans of Waits’s music are treated to his range of dark, hoarse evocations, as well as moments of surprising lightness and beauty. Burroughs’ book is sprightly, its unpredictable expressions paralleled in the design of a set that explodes with interesting juxtapositions and events.

Perhaps its greatest recommendation is the timely moral instruction within its story of corrupting trade-offs and death. In a world where the egregious and immoral schemings of reality TV stars win elections, perhaps its high time to reimpart some stiff German lessons, if expressed in the world-weary words of the Beats. The devil shapeshifts its form yet choices at crossroads remain.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion