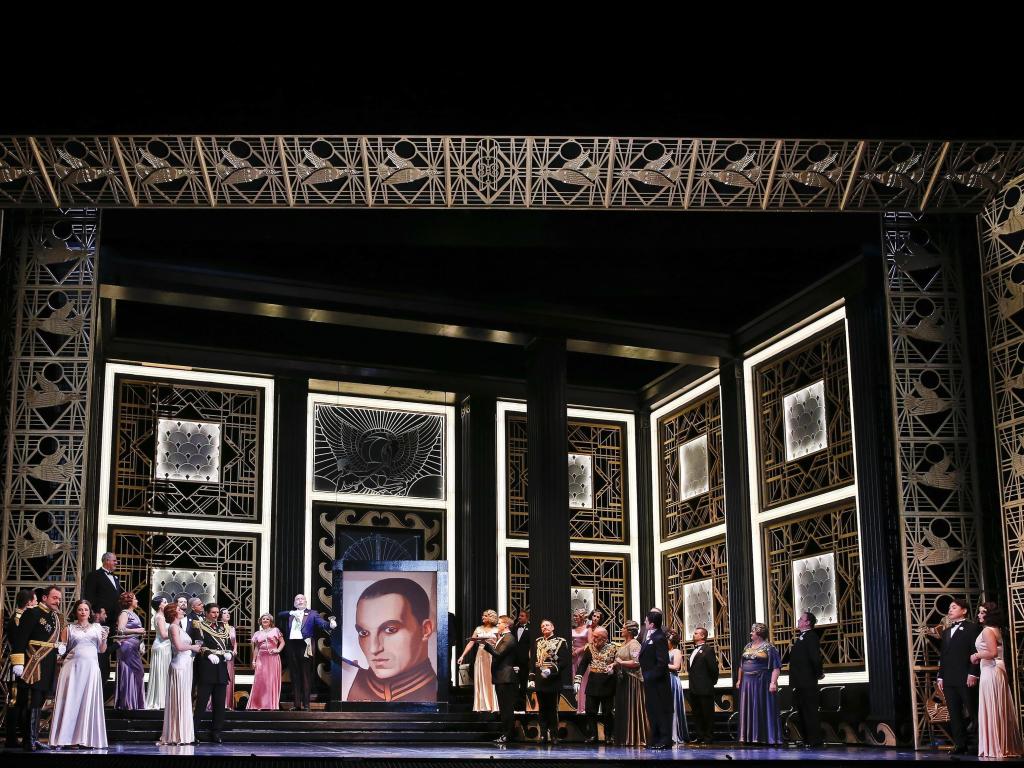

Image: The cast of Opera Australia’s production of The Merry Widow at the Arts Centre Melbourne. Photo (c) Jeff Busby.

Lehár’s famous operetta The Merry Widow (‘Die lustige Witwe’) with a libretto by Viktor Leon and Leo Stein adapted from the play L’attaché d’ambassade (1863) by Henri Meilhac was recognised as a smash hit from its first performance in the Theater an der Wien in 1905. Thereafter it was translated into numerous languages, was transformed into ballet, became the subject of several films and has since been performed on ice. Testament to its international fame and appeal, it was first produced in Australia only three years after its Viennese premiere by the JC Williamson Company in Melbourne’s Her Majesty’s Theatre and frequently revived as the starring vehicle for such favourite sopranos as Gladys Moncrieff, June Bronhill and Joan Sutherland.

The work’s fruity, fin de siècle story centres on Hanna Glawari of humble origin who finds herself a rich widow in Paris whose fortune could save the mythical (and impecunious) Balkan principality of her native Pontevedria.

The music is masterfully crafted with not a dull moment over its three acts. Lehár is an expert at producing a sequence of vibrant ensembles all with spectacular ‘wham-bam’ endings (in this production all downstage under full followspots). The work certainly doesn’t require a long attention span! This brand-new production by Graeme Murphy fully explores (if not exploits) all of The Merry Widow’s energy, colour, verve and sparkle with, as you would expect, a good deal of excellently choreographed dance by some very fine young dancers (curiously unnamed in the printed program). The work still has broad appeal for all ages and it was pleasing to see so many children in the audience.

Image: Stacey Alleaume as Valencienne and John Longmuir as Camille de Rosillon in Opera Australia’s production of The Merry Widow at the Arts Centre Melbourne. Photo (c) Jeff Busby.

The success of any production of the Widow, though, largely rests upon how it looks. Murphy transports the work from the opulent charms of Art Nouveau Paris to a cooler, more sophisticated and glamorous 1920s Art Deco with touches of Bauhaus. It all works, but at a cost. Act 1 was all silver metal screens with a duck motif, smooth imperious pillars in black and gold (Michael Scott-Mitchell, set designer) with pastel, heavy silk gowns (Jennifer Irwin, costume designer) silver shoes and bobbed hair-dos. It looked and felt more like the large foyer of a slick New York hotel rather than a 19th-century Parisian embassy. The starlit garden party of Act II presented a back screen and drape replicating Monet’s waterlilies that were gentler to the eye but overegged with heavily embroidered and beaded Indian and traditional Balkan dress while other guests paraded in hand-painted chiffon flapper dresses adorned with fabric garlands. Already more than a feast for the eyes, a wrought-iron summerhouse and furniture with peacock motif provided yet further visual enrichment and luxuriance. But in Act III we sorely missed Maxim’s mirrors, flora and fauna in Tiffany glass, its feminine curvaceousness replaced by further towering, cold, metallic surfaces, linear angles and a protruding gloss-red staircase that could have been conceived by Le Corbusier. The renowned artistry of both Scott-Mitchell and Irwin is acknowledged, but I would question Murphy on the wisdom of this aesthetic conception. Somehow, it seemed, beauty was confused with glamour.

There were three further aspects that diminished the work’s charm. Sung and spoken in colloquial English, there was a variety of accents from upper-crust British through to mock Viennese and even some ocker creeping in. Of significant concern, all the singers were fitted with head microphones (Tony David Cray, sound designer). This was not ‘sound enhancement’ but blatant amplification such that it often overbalanced the entire orchestra, making it impossible to hear some of Lehár’s subtle orchestration and lush harmonies. It presented a disembodied sound within the theatre and robbed the audience of being able to hear the true qualities of each singer’s natural voice. The translation by Justin Fleming in seeking presumably to make the work as broadly popular as possible, was often disappointingly vulgar and baldly exposed several awkward and unamusing moments.

But focusing on the many positive aspects of this fine performance: first and foremost Orchestra Victoria (Roger Jonsson, concertmaster) was outstanding, performing under the cool, calm and collected direction of Vanessa Scammell it articulated genuine tenderness and affection for the score. Chamber sub-sections were conveyed with gentle and supple loveliness. The Opera Australia Chorus provided a fine presence in both choral sound and theatrical impact (Anthony Hunt, Chorus Master).

Image: (Left to Right): Luke Gabbedy as Viscount Cascada, Jane Ede as Sylviane, Christopher Hillier as Dominik Bogdanowitsch, Agnes Sarkis as Olga, David Whitney as Baron Mirko Zeta, Dominca Matthews as Praskowia, and Tom Hamilton as Konrad Pritschitsch in Opera Australia’s production of The Merry Widow at the Arts Centre Melbourne. Photo (c) Jeff Busby.

The night belonged, however, to returning Australian soprano Danielle de Niese as Hanna Glawari who exuded a telling joie de vivre from beginning till the final curtain. With a swag of international successes in major opera houses, de Niese looked brilliant throughout and displayed outstanding stagecraft skills which convincingly set the tone for the production’s flirtatious high spirits. De Niese’s famous show-stopping aria Vilja was poignantly sentimental and nostalgic. This simple and tender aria, however, provides a rare moment of stillness in an otherwise action-filled Act and it should have been left to speak for itself. Instead, dancers manually raising and rotating the seated soloist on a circular plinth, lifting her higher as she sang higher, was both nerve-wracking to witness and utterly unnecessary. With the unfortunate amplification it was difficult to judge her true voice.

Hanna Glawari’s former lover and intended was an affectingly dishevelled Count Danilo Danilowitsch (sung by Alexander Lewis), rekindling his self-esteem as his romantic feeling for Hanna flowers anew. Stacey Alleaume was an effervescent and appealing Valencienne in her naïve infatuation with Camille de Rosillon (John Longmuir), whose excellent tenor was also a highlight of the production. The opening of Act III with dancing waiters arriving with champagne-laden trays and the following cancan with the delightful, if roguish, grisettes provided genuinely exhilarating entertainment.

And so, despite some issues, this is a must-see production. Highly recommended.

Rating: 4 stars out of 5

The Merry Widow

Vanessa Scammell, conductor

Graeme Murphy, director and choreography

Janet Vernon, creative associate

Michael Scott-Mitchell, set designer

Jennifer Irwin, costume designer

Damien Cooper, lighting designer

Tony David Cray, sound designer

Shane Placentino, assistant director and choreographer

Matthew Barclay, assistant director

Justin Fleming, English translation

Danielle de Niese, Hanna Glawari

Alexander Lewis, Danilo Danilowitsch

David Whitney, Baron Mirko Zeta,

Stacey Alleaume, Valencienne

John Longmuir, Camille de Rosillon

Benjamin Rasheed, Njegus

Richard Anderson, Alexis Kromow

Christopher Hillier, Dominik Bogdanowitsch

Jane Ede, Sylviane

Brad Cooper, Raoul de St Brioche

Luke Gabbedy, Viscount Cascada

Agnes Sarkis, Olga

Tom Hamilton, Konrad Pritschitsch

Dominica Matthews, Praskowia

Opera Australia Chorus

Orchestra Victoria

Presented by Opera Australia

State Theatre, Arts Centre Melbourne

16 November, 2017