Early on in The Nose, two men in the audience stand up and stride out in outrage. “This isn’t the Rooty Hill RSL, it’s the Sydney Opera House!” one of them cries in mock horror at the sheer irreverence of what is unfolding on stage.

The men, of course, are planted and are part of the performance. But on opening night there were a number of genuine walkouts in a production likely to divide opinion smack on the nozzle.

The Nose follows Platon Kuzmitch Kovalev, a social climbing civil servant who one morning wakes up without, well, his nose. Sliced off accidentally by a drunken barber it grows in size to human proportions. Soon it is strutting, independent, around St Petersburg. To add insult to (literal) injury, “nosey”, as Kovalev calls his runaway appendage, seems to command more respect, and have more status, than himself.

Based on a short story by Nikolai Gogol of the same name, The Nose was Dmitri Shostakovich’s first opera. A child prodigy who was writing notable compositions aged just 12, he completed the Nose in 1928 when he was 21 years old (Shostakovich also wrote the libretto alongside Georgy Ionin, Alexander Preis and Yevgeny Zamyatin).

Shostakovich, however, arrived on the wrong side of history. The Nose, with its outrageous comedy and seeming frivolity, fell foul of the Soviet regime. Staged in full in 1930, it was quickly discarded and wasn’t played again in the Soviet Union until 1974, one year before Shostakovich’s death from lung cancer.

Since then The Nose has gained somewhat of a cult following. This production, put together jointly by Opera Australia, Royal Opera and Komische Oper, comes hot on the heels of a critically lauded run in London, and is the first time the absurdist opera has ever been played down under. Directing it with wild exuberance, using a new English translation by David Pountney, is Australia’s Barrie Kosky, the artistic director of Komische Oper in Berlin where The Nose will travel in June.

The Nose has the high-spirited daring of youth on its side. And while clearly lampooning the issues of its time, including police corruption and the suffocating confines of rank, it feels contemporary. That said, experiencing it is a trial in endurance as Kosky, who revels in excess, rarely stands by the maxim that less is more.

Egging him on is Shostakovich’s score, brilliantly conducted by Andrea Molino, which is shocking, violent and unpredictable. At one point an interlude of un-pitched percussion seems to almost crash into the space. Mixed into this are different genres including folk music and the polka.

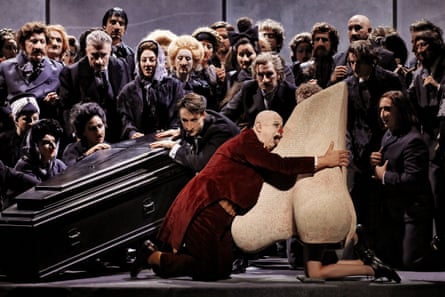

For Kosky, such carefully-crafted chaos has proven too hard to resist. Matching the music head-on, he provides a wild, grotesque, frenzied production that is both surreal and sardonic. Everything about it – from the exaggerated facial expressions and clownish movements to the drag-queen make-up – is over-the-top. Watching it I knew I was meant to be impressed. But I couldn’t help but feel that this was Mr Bean done-up in the excessive costumes of The Capitol in The Hunger Games.

The ensemble pieces, in particular, are a maelstrom of mad disarray. Austrian baritone Martin Winkler reprises his role as Kovalev and it is to his credit that he still manages to command the stage whilst battling against 26 principal singers playing 80 named solo parts. Virgilio Marino as Kovalev’s servant Ivan, a man fond of both a penguin-style waddle and holding his notes a little too long, is also memorable.

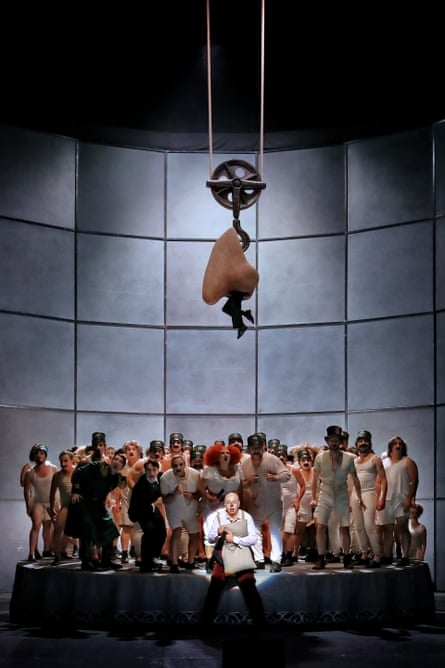

But there if there is one stand-out star it has to be 12-year-old Samuel Wood as the Nose itself: you never see his face but he walks across the city with such youthful swagger I couldn’t help but smile. A tap-dance of giant noses – replete with an exuberant cry of “Thank you Sydney!” – is both zany and euphoric.

Such a carefree jaunt only seeks to highlight Kovalev’s status anxiety, reflected in the music. If this is satire, it is also a monstrous fairytale and a fable on sexual inadequacy and castration. While every other character on stage sports large prosthetic noses, making them look both fantastical and freakish, Kovalev wears a clown’s nose, painted on his face in a raw, rubbed red.

So clearly lacking in adequate stature (not to mention size) he bemoans in genuine despair: a man without a nose “is less than a man”. It’s an ongoing theme. When a surgeon (played with authority by Sir John Tomlinson) comes to see if he can fix the problem he pointedly taps Kovalev’s groin. And when Kovalev is captured by a freak show, full of formidable bearded ladies in stilettos, he is forcibly stripped.

Wearing just a tiny pair of grubby white Y-fronts, his wobbly belly spilling out over his underwear, a mask is attached to his face. Hanging from it – where his nose should be – is a flaccid penis like a sorry elephant’s trunk. It is one of the few genuinely sad, and truly pathetic, moments of the opera.

The Nose is at its best when it is at its most self-aware and self-deprecating (as one character jokes, “you won’t see that in Evita”). But its focus on humour also takes away from potential pathos. Shostakovich admired Gogol’s story, in part because “all comic events [are] in a serious tone ... Honestly, what is funny about a human being who has lost his nose?” he asked. “The Nose is a horror story, not a joke.”

For some, drunk on its droll darkness and vivid depiction of a dystopian society, The Nose will be the best thing they’ve seen all year. But for me, it was a queasy experience that tries too hard and, worse still, was tedious. I ached for less in-your-face farce – less farts, belches and sneezes – and more real emotion, a sense of the true fear and true pain that Shostakovich seemed to so badly want to portray. Penis-mask and tap-dancing proboscis aside, in the end I was left cold.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion